Living off the land: The ugly truth behind black agriculture in America

Black families in America used to enjoy the fruits of their labour, says Korsha Wilson. Now, their descendents are fighting to keep the farmland that’s rightfully theirs

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In Halifax County, Virginia, about 200 miles from the District of Columbia, vibrant green hills bounce out of the earth, and muscular, dark brown cattle rest in meadows alongside farmhouses old and new. Creeks and rivers jut through the landscape like stretched yarn, mixing with soil under crisscrossing tree branches.

This is Virginia’s agricultural belt, far from metropolitan Alexandria or Arlington in the northern part of the state. Agriculture is the largest private industry in Virginia, providing the economy with $70bn (£57bn) annually and employing more than 300,000 people across 44,000 farms. Here, fertile soil yields crops of tobacco, corn, grapes and peanuts, and sustains livestock for small family farms as well as sprawling industrial ones.

Melinda Hyman and William Palmer III remember visiting their great-great-grandfather’s small farm here when they were children. “He had orchards of pear and apple trees and some cattle,” Palmer recalls. Emmanuel Freeman purchased the 1,000 acres of land after the Civil War, building a modest life out of the few liberties the country afforded black people at the time. Freeman married Elsie Barksdale, had 10 children and built a small, two-story house. Like many black families in Virginia at the time, the Freemans lived off their land and hoped to pass it down to their children and their children’s children, a sanctuary of hope and belonging for generations to come.

But while Freeman could nurture the ecosystem on his acreage, he could not control the forces that governed the country during Reconstruction. According to Palmer and Hyman, while running an errand on Main Street in Halifax one day, one of Freeman’s grandsons, Johnny, didn’t move off the sidewalk for a white woman, drawing the ire of shop owners and the local authorities. Johnny ran to the safest place he could think of, his grandfather’s land. A mob followed, and Freeman exchanged gunfire with local authorities before the family’s house and possessions were set ablaze. Elsie and other family members relocated to a small cabin on the property and hid until morning.

It’s a story that Hyman and Palmer keep in their minds as evidence of the challenges black farmers have long faced in their fight for land retention. “I feel like it’s my fight now to stand my ground and keep this land,” Hyman says, even though it is no longer actively used for farming. They and other descendants of Freeman and Barksdale have been fighting a decades-long legal battle to preserve their ownership, a fight that is all too familiar to many black farming families.

Land ownership in America, a precarious notion for both the colonists and the enslaved, took on new meaning during Reconstruction. With hope and the promise of 40 acres of Confederate land, abandoned rice fields stretching across islands from Charleston to Florida in an order written by General William T Sherman, black families settled in the South. But the promise never came to fruition, and former slave owners were given back their lands, forcing black families into sharecropping. Some were able to save enough money to purchase their own land but others ended up owing money to their former owners. By 1910, black farmers operated 212,972 farms in America, but, like Freeman, they found land ownership didn’t negate being black in the Jim Crow South.

“There was a severe backlash to that land acquisition,” says Leah Penniman, author of Farming While Black: Soul Fire Farm’s Practical Guide to Liberation on the Land and founder of Soul Fire Farm in Upstate New York. “There was burning of homes, lynchings ... People were literally driven off of the land.”

Many of those farmers’ descendants are now scrambling to prove and retain ownership, a complicated task thanks to a legal loophole that allows distant relatives and developers to obtain rights to lands that have been in families for generations.

According to the 2017 US Agricultural Census, the number of black farmers has increased to 45,508, a fraction of the 3.2 million white farmers in the same report. Yet black farmers are losing land at a higher rate than their white counterparts. Since 2012, about 3 per cent of black-owned farmland has been lost, compared to 0.3 per cent of white-owned farmland.

The loss has been particularly severe in the South, where paperwork on black families is thin and wills infrequent due to generational distrust of the legal system. Jillian Hishaw, an agricultural lawyer and founder of Family Agriculture Resource Management Services, works with minority farmers in the southeast to help protect their lands, connecting families with lawyers and helping them navigate real estate law, raise funds for legal fees and discover tax breaks. “Oftentimes, these cases are long and obtuse and require a lot of time,” she says.

Unravelling complex agricultural law also uncovers harsh histories. “I’ve worked with clients where the deed for their land was in the family’s slave holder’s name,” Hishaw says. She and the family had to contact the slave owner’s descendants and ask them to sign the deed over to the black family that had lived there for generations. Making it even trickier to prove ownership is the fact that many black families’ documents use nicknames instead of legal names – or sometimes no names at all.

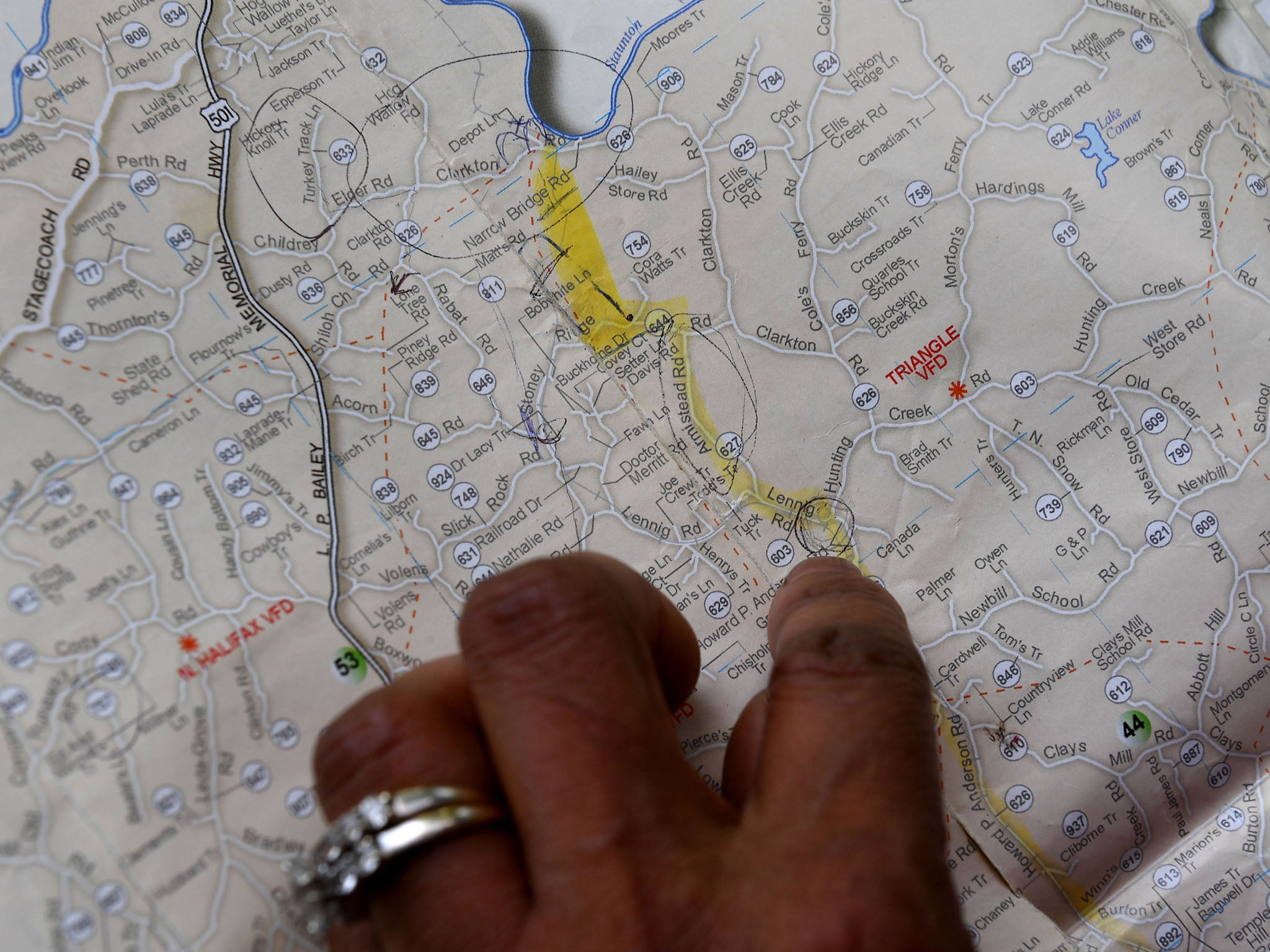

Hyman found out firsthand how discrepancies in court documents can leave land owners vulnerable. In a wire shopping cart, she transports historical records, deeds and letters sent to county and state treasurers as well as congress and the Obama administration. The cart also contains records of the property taxes she has paid, but those payments are missing from court documents. She says she learned that Freeman remarried after Elsie Barksdale died and had 10 more children with his new wife. He died in 1925 without a will. When his second wife died, ownership was transferred to the 20 children and then to the grandchildren. Calls to county and state officials to prove ownership have led nowhere, and in 2018, 30 acres of their original 99 were sold in a partition sale pursued by distant relatives. Hyman turned to the Internet for help and found an article about Hishaw. “As I looked into it, I realised that there were a lot more families this was happening to,” she says.

There was burning of homes, lynchings ... People were literally driven off of the land

Hishaw, who connected with Hyman more than a year ago, said the case resembled her own family’s story. Hishaw’s grandparents owned a farm in Oklahoma for which they paid a local attorney to make yearly tax payments, but she says the payments were never sent and the attorney pocketed the money. “We lost our farm in a tax lien sale because they said we hadn’t paid taxes,” she remembers. She wanted to make sure the same didn’t happen to the Freeman family. “It was one of the worst stories that I’d heard.”

In over 20 states, when landowners die without a will, their assets, including land, are given to their heirs (a spouse or children), Hishaw says. Over time, 10 heirs can become 100, and any one of them can force a “partition sale” of their acreage or the whole property, according to Virginia state law. “If one of those heirs sells to a developer, then that developer becomes a partial heir to the land,” Hishaw adds. And a developer can force a sale by appealing to the court and saying, “We need to clean up this deed so I can use the land.”

Lack of estate planning is not unique to black families, says Thomas Mitchell, professor of law at Texas A&M University and an expert on discrimination in real estate and estate planning law, but it is more prevalent. A study by the US National Libraries of Medicine found that 24 per cent of older black Americans have some form of estate planning, compared to 44 per cent of older white Americans. The problem is especially acute for black farmers because access and opportunity have historically been so hard to come by.

“After the Civil War, black people had basically no access to attorneys that would represent them,” Mitchell says. They also weren’t given tools to understand real estate law or create wills. “They didn’t have access to lawyers, business planning, education ... Estate planning is correlated with education levels.”

***

“Welcome to Belle Terry Farm,” Tashi Terry says as she swings a rusted metal gate open for her father, Aubrey Terry, to drive his pickup truck through. The cattle farmer has lived in Halifax since 1963, when he bought a 170-acre plot with his siblings. Belle Terry Farm raises cattle to be sold locally and grows greens and squash with plans to open a pumpkin patch this fall. The land is a postcard of sturdy walnut trees poking out of hills like needles in a pin cushion, swathes of Technicolor flowers and the Dan River, which swells and spills into a nearby meadow after heavy rain.

Terry and his siblings have homes on this property and had children who made the grounds and farming equipment their playgrounds. Halifax’s population is a little over 1,300, and the area has seen a spike in interest from real estate developers. “It started a few years ago when I saw people canoeing through the river,” Aubrey Terry says.

The eldest Terry brother died in 2015, and because he didn’t have a will, his wife inherited his part of the estate. “She wanted to sell her portion of the property, and we don’t, so she hired attorneys to work with,” Terry says. In January, while tending to the cattle on the farm, he and his son saw a man on the property. “He said he was an auctioneer and he was here on behalf of the Bagwells,” Terry remembers. After filing a trespassing charge, the Terry family learned that Halifax law firm Bagwell & Bagwell had contacted nieces and nephews living in Atlantic City who were listed as heirs to force a partition sale. Those nieces and nephews “have nothing to do with the farm at all,” Tashi Terry says. “They’ve never even lived here.”

Like many other rural areas, Halifax’s once affordable acreage is considered prime real estate. That’s also a familiar story for many black families who settled where they could, finding shelter and safety in the communities they built, only to be pushed out a generation or two later.

George Bagwell, owner of the firm pursuing partition sales in the Terry and Freeman cases, says he understands why some family members want such sales. “This is one of the most depressed areas in Virginia,” he says. He grew up in the county in the 1960s, when the area was mostly tobacco farms, and remembers when the passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994 led businesses out of the county. Industry and opportunities fled to other parts of the state, and families followed.

While most lawyers in the area used to do partition sales, he says, now most don’t because it’s too hard. “It gets so that when you have four, five, six people, no one wants to keep the houses up or the barn, but they might still pay the taxes,” he says. “There’s a whole lot of black families in that position.”

The Agriculture Improvement Act of 2018, also known as the Farm Bill, included an amendment designed to help solve multiple claims of ownership and provide access to federal funds for farming. The amendment, co-sponsored by Senator Doug Jones (Democrat, Alabama), provides owners with a “farm number” to use when applying for funds. “With a farm number, heirs can access resources and support from federal programmes run by USDA and other agencies, like Fema [the Federal Emergency Management Agency],” Jones says. He says he learned about heirs’ land loss and how it impacts black communities after farming advocacy groups reached out to his team. He hopes farm numbers “will help address one facet of this issue” by giving heirs a way to prove ownership.

After the Civil War, black people had basically no access to attorneys that would represent them

Mitchell is also working with lawmakers to introduce the Partition of Heirs Property Act, most recently passed by the New York legislature and introduced in 10 other state legislatures, including Virginia’s. The act would require “tenants in-common”, those living on the property, to come to an agreement about the sale of the property rather than one heir being able to force a partition sale with a developer. The goal is to help black families retain the asset of their families’ land, Mitchell says. “Stripping people of their real estate is stripping them of their wealth,” he says.

Penniman and groups such as the Southeastern African American Farmers’ Organic Network and the Black Family Land Trust are also working to help black, Latino and indigenous farmers secure ownership of land and encourage new generations of farmers. “Ninety-eight per cent of rural land belongs to white people, and that’s so imbalanced,” Penniman says. “Land is the scene of the crime, but she wasn’t the criminal.”

While there has been a substantial loss of land, Mitchell says, there is still room for cautious optimism about preserving what’s left. “It’s an incredible and remarkable history that African Americans acquired 16 million acres of land,” he says. “I focus on what happened after that.”

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments