Team sets out to replicate Shackleton's epic journey

Adventurers plan to row 800 miles across Southern Ocean in 22-foot boat

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

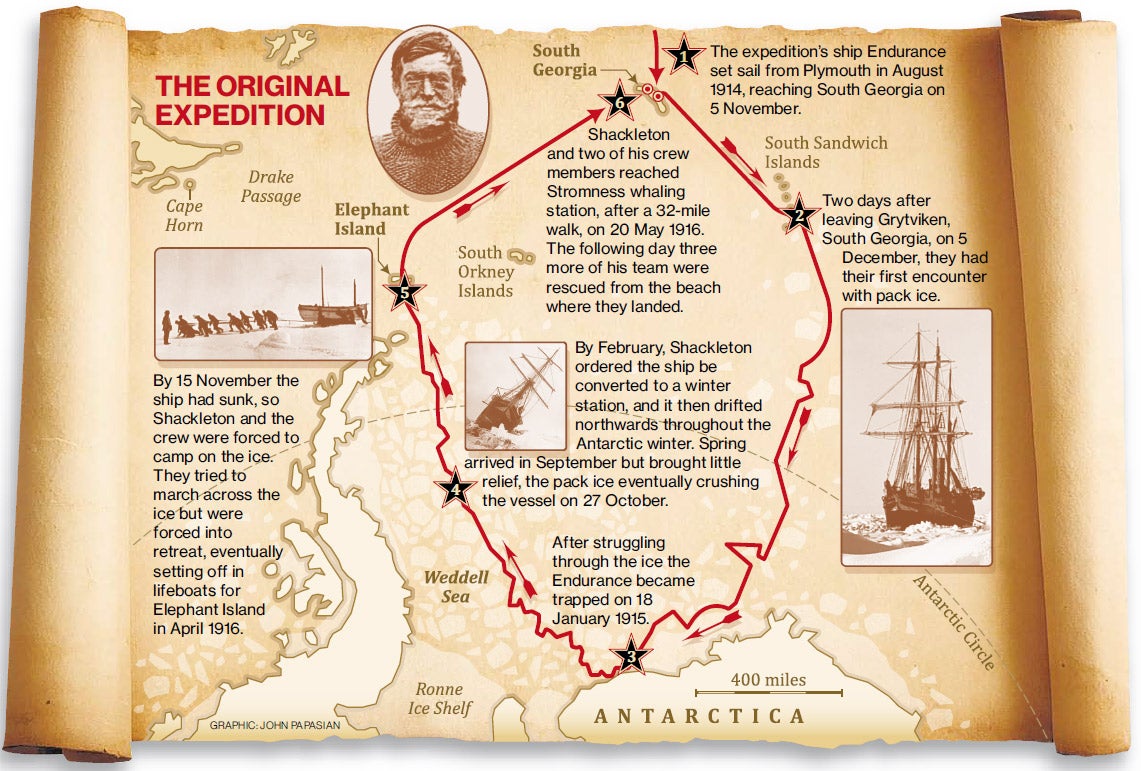

Your support makes all the difference.Sir Edmund Hillary called it "the greatest survival story of all time", and he knew a thing or two about the challenges posed by nature. Today a British-Australian team will embark on an attempt to retrace Ernest Shackleton's epic 1916 journey across the brutal Southern Ocean, equipped only with the polar explorer's early 20th-century gear and technology. With five other men, Shackleton rowed across 800 miles of icy ocean from Antarctica to South Georgia, then trekked 32 miles across the island's mountainous interior to seek help for the rest of his crew, who were stranded on Elephant Island. Their ship, the Endurance, had sunk there after becoming trapped and crushed in pack ice. Against the odds, all 27 crew survived.

Leading the modern expedition is Tim Jarvis, 46, a British-Australian environmental scientist and a veteran polar explorer. Joining him are five experienced sailors and mountaineers.

The team will face the same privations as their predecessors as they row across the rough Southern Ocean in a replica of Shackleton's 22-foot wooden lifeboat, with only the stars to guide them, then cross South Georgia's glacial peaks without a tent. Woollen clothing will be their only protection from the elements, and they will subsist on pemmican, a stomach-churning mix of dried meat and lard.

Shackleton's team was battered by heavy seas, and the conditions are likely to be challenging this time. While it is summer in the Southern Hemisphere, even during the hottest month in South Georgia, February, temperatures average just 9C.

Mr Jarvis was approached in 2008 by Alexandra Shackleton, the explorer's granddaughter, who suggested that he honour her grandfather's legacy a century on. Since then he has become a father to two boys. "Had kids been around when I started planning this expedition, I may have thought twice about doing this," he told Australia's ABC radio today from southern Argentina, where his team is making its final preparations.

The potential hazards, he said, would include capsizing or hitting an iceberg – their boat has no keel – as well as landing on South Georgia "without being bashed against the rocks". The land crossing would be "heavily crevassed and quite dangerous".

Despite those risks, he was looking forward to emulating a journey which "well and truly bookmarked the end of the heroic era of exploration that started in 1895, when the first person set foot on the Antarctic, and finished with the First World War". He said: "This is the ultimate, this is the biggest expedition you could do."

Shackleton, who joined Robert Falcon Scott on his first trip to the South Pole in 1901 but later became his arch-rival, was aiming to cross Antarctica from coast to coast. He and his team set sail from England in August 1914, and by December of that year had reached South Georgia. However, by January of the following year they were trapped by the pack ice which eventually crushed the Endurance.

After she sank, Shackleton realised the crew's only hope of rescue lay with Norwegian whalers stationed on South Georgia. His party reached the island after rowing for 15 days.

Mr Jarvis's team will be shadowed by a modern support ship which will only assist in an emergency. Ten members of the public have paid A$30,000 (£19,343) each for a berth on the vessel.

The team will also collect data in an effort to draw attention to the impact of climate change. "Shackleton was trying to save his men from the Antarctic," Mr Jarvis said before leaving Sydney last month. "Now we're trying to save Antarctica from man."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments