Ned Kelly granted funeral – 130 years after execution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.More than 130 years after he was hanged for shooting a policeman, the 19th-century bushranger Ned Kelly is finally to be laid to rest. But in death, as in life, he continues to polarise Australians, with some warning that his grave should not become a shrine.

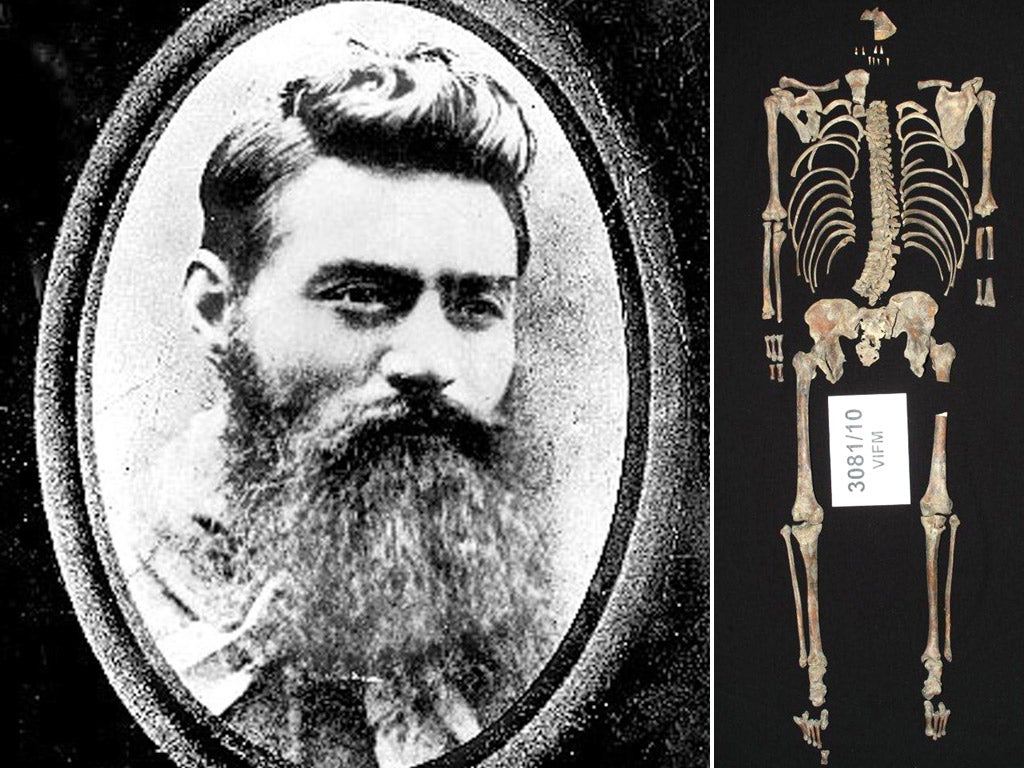

Kelly was buried in the grounds of Old Melbourne Gaol in 1880, but his remains were later exhumed and reburied in a mass grave outside Melbourne's Pentridge Prison. In 2008, his bones were discovered along with others in a remote part of the former Pentridge complex. In September, Kelly's remains – missing a skull – were identified.

Now they are to be handed back to his family's descendants, who plan to hold a funeral, in accordance with Kelly's last wish. The day before he was executed, the Irish-Australian wrote to the prison governor, asking "permission for my friends to have my body that they might bury it in consecrated ground".

Anthony Griffiths, a grandson of Kelly's younger sister, Grace, said yesterday that the family hoped to bury him in a churchyard near Glenrowan, the rural Victorian town where he was captured after two years on the run. His mother, Ellen, and several of his siblings are buried there in unmarked graves.

"Our aim is to give him a dignified funeral, like any family would," said Mr Griffiths, whose donation of a DNA sample helped forensic scientists to identify Kelly's remains. He said the family might also hold a public memorial service.

That idea has infuriated the secretary of Police Association Victoria, Greg Davies, who said Kelly was no better than Carl Williams, a notorious Melbourne gangster murdered in jail last year.

"He wasn't a Robin Hood," Mr Davies said. "He didn't steal from the rich and give to the poor; he stole from everyone and kept the proceeds for himself." The Victorian Attorney-General, Robert Clark, said the return of Kelly's bones was "not a matter of paying homage", but of finding an appropriate resting place for them.

His grave, though, is likely to attract tourists and devotees of his story, which has inspired several films and numerous books, including Peter Carey's Booker Prize-winning True History of the Kelly Gang. A legendary figure, Kelly is regarded by some as a thief and murderer and by others as a champion of the underclass in a harsh colonial society.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments