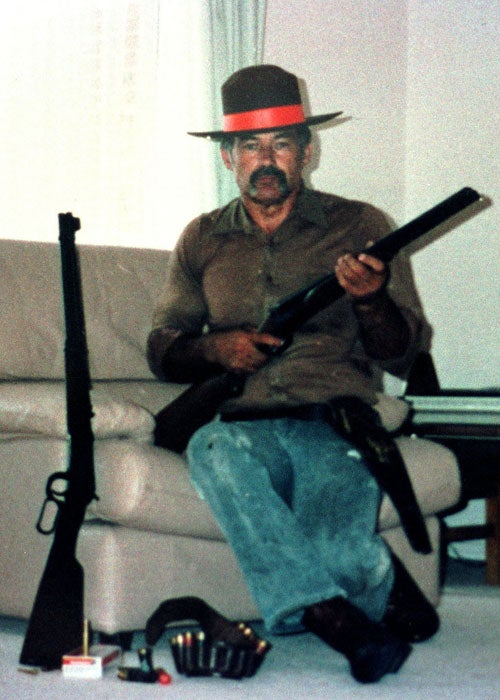

Did Australia's backpacker killer have an accomplice?

Ivan Milat was jailed for seven murders. New evidence suggests he did not act alone

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Next week will mark the 20th anniversary of the last time Simone Schmidl was seen alive. It was at 8.15am on Sunday 21 January 1991 that she left her lodgings in Sydney's western suburbs to hitch a lift to Melbourne, where she was due to meet her mother off a plane from Germany.

Twenty one year-old Simone, from Regensburg near Munich, never turned up. The young German tourist, who had been backpacking around Australia and New Zealand, had set off in yellow singlet, khaki shorts and stout walking boots for the 550-mile journey south. Her backpacker friend, Jeanette Muller, had tried to persuade her not to hitchhike and even offered her some money to take the bus instead.

But Simone, a striking woman with dark dreadlocks, was determined to thumb her way to Melbourne. With no sign of her daughter at the airport, her mother Erwinea alerted the police, but a nationwide search for the bespectacled young German with the friendly, easy-going manner failed to produce any clues to her whereabouts. It was to be almost another three years before Simone's fate became known.

In November 1993 her body was found in the Belanglo State Forest in the New South Wales Southern Highlands, a vast bushland that was to become synonymous with the reign of terror of Australia's serial killer, Ivan Milat. Seven tourists died in the murders, including Britons Caroline Clarke, from Farnham in Surrey, and Joanne Walters, from Maesteg in Wales. They were both in their early 20s.

But more than 14 years after Milat was convicted of the killings and sentenced to life imprisonment, a question remains: did he have an accomplice?

The discovery last August of another body in the Belanglo State Forest served to reinforce the area's grim history and renewed speculation about a second killer. While the remains of the young woman had been there for about 12 years or less, long after Ivan Milat was put behind bars, the fact that the bones were scattered clearly suggested foul play. Five months later, both the victim and the killer remain unidentified. But why did the murderer choose a site already so strongly associated with violent crime? Or did the killer or killers have such a detailed knowledge of the area that they were confident of getting away with it?

More crucially, if what Justice David Hunt, who presided over Milat's 1996 trial, acknowledged in his summing up was true – that two people were almost certainly responsible for the backpacker murders – did it suggest Milat's partner in crime continued to be active long after Milat was arrested?

The most compelling evidence to support the accomplice theory comes from Gerard Dutton, the ballistics expert who proved that the Ruger rifle hidden in the cavity wall of Milat's home fired the same bullets that were found in at least one of the victims. One and a half decades after his evidence helped to convict Milat, he told me he had no reason to change his mind about the two-killer scenario. "Looking purely from the firearms evidence, it's suggestive of a second person. It's not conclusive proof, I have to say, but to my way of thinking it suggests that," he insisted from his new base in Tasmania.

Sergeant Dutton bases his theory on the fact that cartridge cases found near the bodies of two other murdered German backpackers, Gabor Neugebauer and Anja Habschied, were from two different brands of ammunition fired from different guns. "There was no crossover of one type of cartridge being used in another gun. One brand was used in one gun and another brand in the other," he explained. "That to me is suggestive of two people with two guns and two different boxes of ammunition. Whatever they were doing, whether they were target shooting at that time, suggests there were two different people. That's not definitive proof, but it's more probable."

Sgt Dutton, who is recognised as one of the world's most experienced ballistics experts, cannot say whether the bullets found in Neugebauer's skull came from different guns because they were too degraded by the time they were found. But they were fired from a .22, the same calibre as the Ruger rifle used on Caroline Clarke. All the bullets found in Clarke's skull were from the same gun because the marks on them matched those left on the bullets during test firing from the breech bolt found in Milat's cavity wall.

The ballistics expert also noted that the two British girls were killed in markedly different ways. While Clarke was shot 10 times in the head, Walters was repeatedly stabbed. Sgt Dutton agreed it was possible one of the killers might not have been able to knife his victim in cold blood and preferred pulling a trigger. "That's a reasonable explanation, but could we say definitively? Probably not," he admits. But having "two very different ways of death and no crossover of firearms evidence" forced him to conclude there were two killers rather than one.

Dr Rod Milton, the eminent forensic psychiatrist who was used as a profiler on the case, also sticks by his initial assessment that there were two offenders. He bases his conclusion on the "very, very different" methods of murder of the two British women.

Now in retirement, Dr Milton continues to believe the two-killers theory. "One knows the other and feels inferior to him and is a bit embarrassed being seen by the other one. It seems to make sense," he explains.

"When you look at Milat, he's a cold, distant person who might have fired shots into the head. He was more deliberate. He was much more rigid, whereas the other one gave the impression of being impulsive and sadistic. The nature of the actions suggested two people," Dr Milton insists.

Yet, according to Clive Small, the police chief who was in charge of the investigation, it is because Milat was such a complex character that it is equally possible to accept he acted on his own. "He was a loner – I don't believe he trusted anybody else," the former police officer told me. On the occasions when his intended victims escaped, including British backpacker Paul Onions, Milat was alone. Mr Small points to the backpackers' clothing and camping gear, which the killer kept as souvenirs. All that was used to kill his victims was only in Milat's possession. "So everything points to him being by himself," Mr Small concludes.

With or without an accomplice, what is beyond question is that Ivan Milat was almost certainly responsible for many more deaths than the seven young travellers for whose murders he was convicted. Detectives looked at 43 missing persons cases after the trial and 16 unsolved murders that fitted the style of the backpacker killings. Mr Small thinks that Milat could have been responsible in at least three of the cases, but other police sources believe the true figure is much higher.

If he was responsible for any of them Milat is not saying. It is all part of the game he plays with his accusers, while harbouring the hope that one day he will be set free from what he describes to relatives as his "sunless cement cave", at Goulburn Maximum Security Prison, just down the road from where his victims were slaughtered.

In a further reminder of the macabre history of the Belanglo State Forest, another body was found there in November. And reinforcing the evil connotations of the Milat name, a young relative of Ivan's was among those charged with the murder of the teenager allegedly hacked to death there.

While the latest killing had nothing to do with the terror perpetrated by Australia's infamous serial killer, the forest continues to fox those trying to find answers to its past. Specifically – is the second killer still at large?

Roger Maynard, who covered the backpacker murders from the early 1990s, is the author of 'Milat – Belanglo: The Story Unfolds', published by New Holland

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments