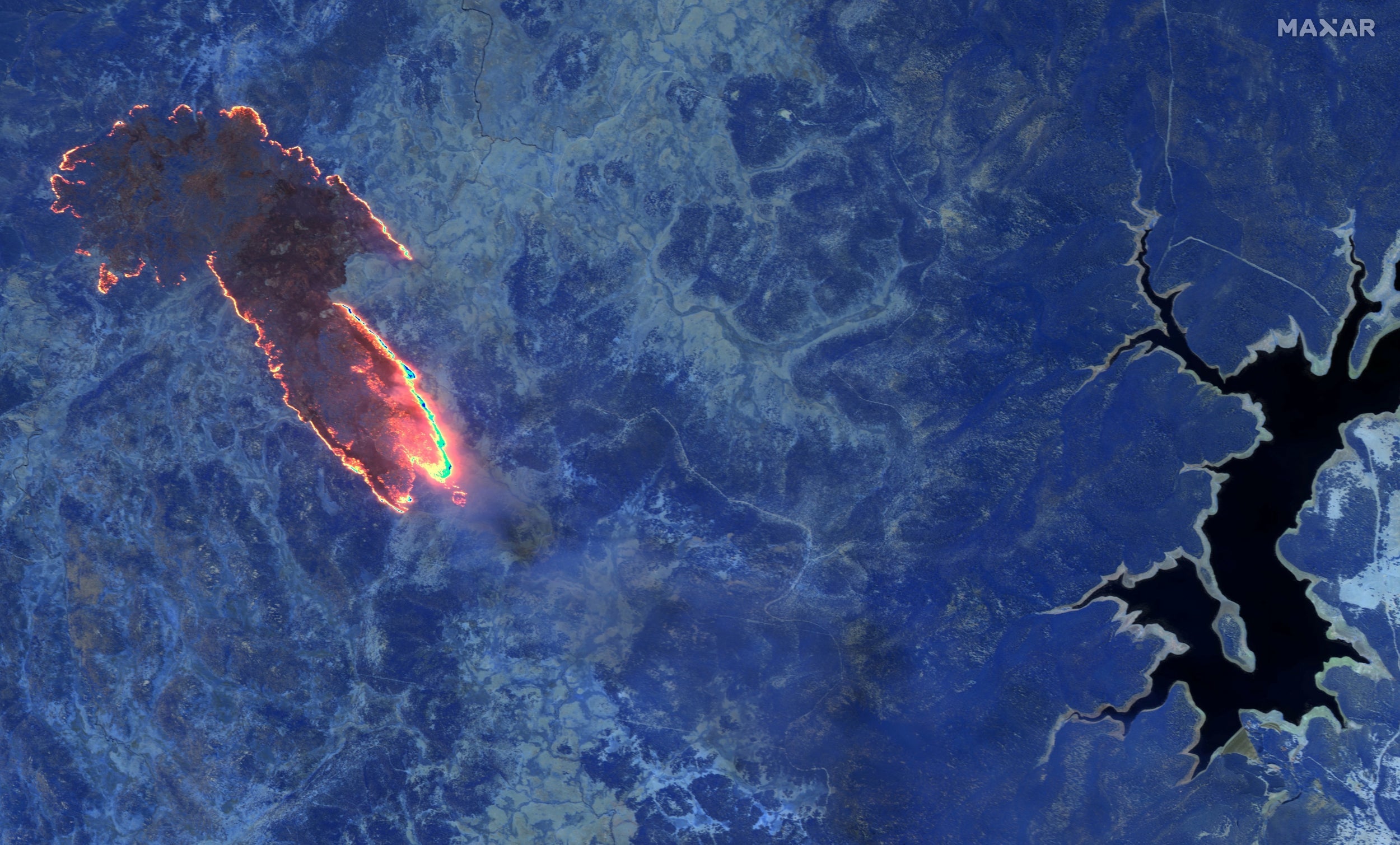

As Australia burns, the smallest species could be lost forever to the flames

Blaze after blaze sweeps across the country, leaving destruction behind. Entire ecosystems face unprecedented risk, says Helen Sullivan

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Tanya Latty, an entomologist at the University of Sydney, started studying a species of velvet worm 18 months ago, she thought it was just a side project.

“It’s an adorable, adorable animal,” she says, speaking on the phone from her home in Sydney. The worms of the phylum onychophora are cousins of arthropods and somewhat resemble caterpillars. They have a “beautiful blue velvety texture” and “cute little stubby antennae”, Latty says. The worms sleep together in a pile, she notes, and for that reason she and her colleagues have been trying to popularize the phrase “a cuddle of velvet worms” as a collective noun.

Velvet worms are predators; they have pairs of clawed legs down the length of their bodies, and they catch prey using glue shot from nozzles on their heads. Often, a single worm will catch the prey, and others will then join the feast. Velvet worms are incredibly social; studying them provides clues to the evolution of social behaviour in arthropods. And they give birth to live young, which remain with their parents for a period before shuffling off.

They also happen to live in one of the national parks in the Australian Capital Territory, an area badly affected by the recent wildfires. So far the fires have destroyed more than 40,000 square miles, threatening entire species, costing 26 human lives and exacting billions of dollars in damage. Latty will not reveal the worms’ exact location; people tend to poach them to sell or keep as pets. But she worries that the rotting logs they inhabit have not protected them from the blazes.

Moreover, like many endemic insect and arthropod species, velvet worms are highly local. Not only do the particular worms Latty studies not occur outside Australia, their ranges are very small. If a large segment of the population is wiped out, the loss significantly affects the genetic diversity of the species, reducing its ability to respond to future changes in the environment.

What began as a side project may soon become a captive breeding programme, with Latty using the live worms she keeps in her lab to save the species, Euperipatoides rowelli, as a whole. “We collected some thinking, you know, there’s lots of them in this one field site, it’s fine,” she says. “And then the fires rolled through.”

It may be a month before she and her team can gain access to the field site where her velvet worms live. “As an ecologist,” she says, “it’s a very tragic thing to find yourself having to think about, ‘what if my species is now extinct?’”

Australia is megadiverse, meaning that it belongs to a group of countries that together are home to 70 per cent of the world’s biological diversity but make up just 10 per cent of Earth’s surface. The nation harbours 250,000 insect species, of which only about one-third have been named. Like insects everywhere, most elude appreciation.

40,000

The number of square miles the fires have destroyed

“Insects have the whole world on their shoulders,” Latty says. She is an author of a “road map for insect conservation and recovery” that was published earlier this month by a group of 70 scientists in research journal Nature. Insects are best known as pollinators, she said, but they play a critical role in waste management, too. “We’re not overrun in our own waste because insects are doing the hard yards of cleaning that up for us,” she says. “And they’re doing it for free.” The key to protecting them is protecting their habitat, she adds.

Kate Umbers, a biologist at Western Sydney University, is similarly worried about – and unable to reach – her own study subjects, which live in Kosciuszko National Park, in New South Wales. National parks across the state are closed because of the fires.

Umbers studies the Australian alpine grasshopper. Like mood rings, the males change colour depending on their body temperature; they are black when their body temperature is lower than 50F (10C) but turn bright turquoise once they hit 77F (25C).

“They’re really spectacular, and they’re the only grasshopper we know of that does a colour change like that,” says Umbers, speaking from her lab at the foothills of the Blue Mountains. “They’re also the only grasshopper that we know of that has really ferocious fights.”

Male Australian alpine grasshoppers wrestle, kick and bite each other in pursuit of a mate. The thermocolouration seems to be an indication of fighting ability, too, says Umbers, who did her doctoral thesis on the species. The definitive data on why the grasshoppers change colours is expected to be collected next year by an incoming doctoral student – provided the population still exists.

Her field site, less than two miles from the nearest fire, “is just hanging on for now”, Umbers says.

“It’s possible, because grasshoppers can burrow into vegetation, that they can hide in very tiny spaces, that many of them will make it through the fire,” she says. But any survivors would need to be able to find something to eat, which is not assured. The grasshoppers thrive near water, particularly around the tree line of snow-gum eucalyptus. “So they don’t do well when things dry out,” Umbers says. “Which is unusual again for a grasshopper. Some of them even go swimming.”

Umbers’s swimming grasshoppers, like Latty’s velvet worms, are short-range endemic species. Multiple fires, occurring too soon after one another, could eventually spell the end for the species.

She calls the current fire season “deeply, deeply troubling – far worse than anything I’ve ever experienced in my life. It’s really quite frightening in an ecological sense.”

Rain is not predicted to arrive until March. In the last six weeks Umbers has watched fires edge closer to her house from the north, west and south, and she has already had to evacuate her house once on a catastrophic fire day. “It’s a slow, creeping stress,” she says.

Some species benefit from fires. Australian fire beetles are known to head towards burnt areas to mate; infrared receptors on their abdomens allow them to detect heat, and, according to a study by the Western Australia Museum, the beetles usually disappear from freshly burnt areas within three days of arriving.

We’ve introduced a medley of species that like to prey upon our native species. Fire can become that one thing that knocks a species over the edge

Native predators also take advantage of the destruction. Black kites and whistling kites have even been known to light fires using burning sticks carried in their talons or beaks from areas that are on fire, in order to capitalise on burnt or exposed prey – they also feed on fleeing grasshoppers on the edge of blazes.

But wildfires create opportunities for invasive species, too, and exacerbate ecological problems already underway. Feral cats travel long distances towards burnt areas to prey on fleeing native reptiles; in Australia, feral cats eat as many as 650 million reptiles each year.

One-third of Kangaroo Island, a government-declared bee sanctuary off South Australia, has been burned so far this fire season, threatening the “last remaining pure stock” of Ligurian honeybees in the world, the ABC network has reported. Foreign honeybees have an advantage because they can abscond with their queen in the face of threats, Latty says. Native stingless bees can’t – their queens can’t fly.

“It’s not necessarily just the fire that’s the problem,” says Dale Nimmo, a fire ecologist at Charles Sturt University in Sydney. “We have landscapes that are really highly modified. We’ve cleared huge amounts of our landscapes for agriculture and urban areas. We’ve introduced a medley of species that like to prey upon our native species. Fire can become that one thing that knocks a species over the edge.”

In the Stirling Ranges, 250 miles from Perth, in Western Australia, Leanda Mason studies trapdoor spiders. Stirling is one of 36 “biodiversity hot spots” around the world, which Conservation International has described as “regions where success in conserving species can have an enormous impact in securing our global biodiversity”. Between Boxing Day and New Year’s Day, wildfires burned more than 150 square miles of the region.

The saddest thing I’ve ever seen is an image of a trapdoor spider that was obviously trying to hold its lid shut and the fire came through, and it was burnt alive

Trapdoor spiders are intensely solitary creatures; a female digs a burrow, creates a lid for it and can live there for years, hardly moving. In 2018, Mason, of Curtin University, published a paper noting the death of a 43-year-old trapdoor spider – the world’s oldest known spider – that had been studied in the wild for four decades by Barbara York Main, Mason’s mentor.

Trapdoor spiders take several years to reach sexual maturity, and because they hardly disperse, their colonies are fairly confined. Several distinct species can arise and be found together in a small area such as along creek line.

Mason’s doctoral thesis focused on the conservation threats faced by trapdoor spiders. She found that trapdoors, burrowed underground, tended to survive fires; sometimes they burrowed out a different way to avoid scorpions and centipedes that were looking for something to eat after the fire or that were taking refuge themselves.

But when the trapdoor spiders’ food supply – typically smaller insects and arthropods – was affected, perhaps by an invasive species of grass, the spiders tended to die within a year. Mason worried that, because trapdoors take so long to mature and don’t reproduce often, an increase in the frequency of wildfires – which is what climate scientists predict for Australia – could wipe out trapdoor spiders that had not had the chance to reproduce.

Mason hasn’t been able to visit her field sites and doesn’t know what is left of them; she tries not to imagine it. “The saddest thing I’ve ever seen is an image of a trapdoor spider that was obviously trying to hold its lid shut and the fire came through, and it was burnt alive,” she says.

“Yeah, fire is just a bit devastating.”

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments