Australia mulls posthumous apology for Olympian Peter Norman, blacklisted for his role in the black powers protest in 1968

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

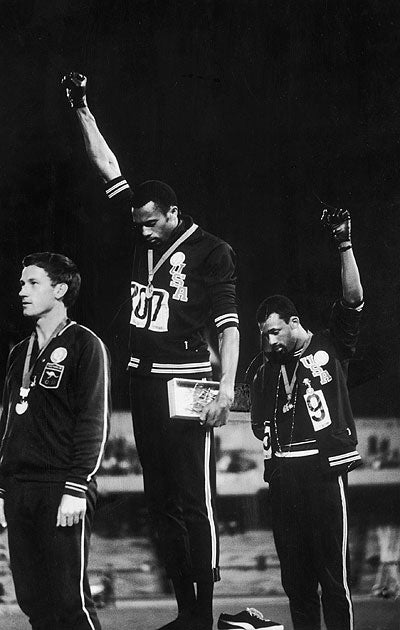

Your support makes all the difference.It is one of the 20 century’s most powerful images: African-Americans Tommie Smith and John Carlos raising their fists in a “black power” salute at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics. But little is known, even in his native Australia, about the third man in the picture, Peter Norman, who stood proudly alongside his fellow athletes, supporting their protest.

The incident, which took place during the 200-metre medal ceremony, caused an uproar. Smith and Carlos were sent home, and later received death threats. But while their reputations were rehabilitated within a decade, Norman, the silver medallist, remained shunned by the Australian sporting establishment. At the Sydney Games in 2000, he was the only homegrown Olympian not invited to perform a lap of honour.

Last night, belatedly, Australia was set to make amends, with federal parliament expected to apologise for the way he was treated. Norman was not there to hear it; he died of a heart attack in 2006, aged 64, having suffered from depression, ill-health and alcoholism. But his 91-year-old mother, Thelma, and his sister, Elaine Ambler, travelled to Canberra for the occasion.

The MPs were due to support a motion recognising Norman’s “extraordinary athletic achievements” – 44 years on, his 20.06-second sprint is still an Australian record. The motion also acknowledged his bravery in supporting Smith and Carlos, and his role in “furthering racial equality”.

Mr Norman certainly paid a high price for that. Despite qualifying for the 100- and 200-metre sprints, he was not selected for the 1972 Munich Olympics, and retired soon afterwards. He was devastated to be excluded from the Sydney Games – although the US team, appalled by the snub, invited him to stay with them, and track legends Ed Moses and Michael Johnson treated him like a hero.

Evidence of the high regard in which he was held in the US came at his funeral, where Smith and Carlos delivered eulogies and carried his coffin. Yet even now the Australian Olympic Committee is keeping its distance. It declined to support the parliamentary motion, claiming it was “incorrect” that Norman was punished for his part in the Mexico City protest.

On their way to the podium, the two Americans had told Norman what they intended to do. He helped them plan the moment, suggesting they each don a black glove. On his tracksuit he wore a badge of the Olympic Project for Human Rights, an anti-racism organisation. He explained afterwards: “I believe that every man is born equal and should be treated that way.”

Andrew Leigh, a Labor backbencher who proposed the motion, told Fairfax newspapers yesterday: “In the simple act of wearing that badge, Peter Norman … showed us that the action of one person can make a difference. It’s a message that echoes down to us today. Whether refusing to tolerate a racist joke or befriending a new migrant, each of us can – and all of us should – be a Peter Norman in our own lives.”

The black power protest was the subject of a documentary, Salute, made by Norman’s nephew, Matt, who had been shocked to discover how few Australians knew the identity of the third man in the celebrated photograph.

“He is not recognised for the incredible times that he did,” Matt Norman said in 2008, when the film was released. “And he’s not recognised for standing up for something that he thought was right. He was sacrificing glory for a greater cause, and we need people like that.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments