What every stressed yakuza mobster needs: A morale-boosting magazine

In-house tabloid offers tips on board games, haikus and a letter from the Yamaguchi-gumi outfit’s godfather

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Japan’s biggest crime syndicate, the Yamaguchi-gumi, has produced an in-house tabloid magazine with features on fishing and board games and a morale-boosting message from the outfit’s godfather.

The eight-page publication warns the syndicate’s roughly 27,000 members that with times getting tougher, they must work harder to protect the values and codes of the yakuza.

An entertainment section contains accounts of fishing trips by its bosses, along with satirical haikus and tips on how to play traditional board games such as Go and Shogi.

The yakuza have traditionally operated openly in Japan, with city centre offices and mobsters who carry business cards in their suits. The century-old Yamaguchi-gumi is based in a high-walled central compound in one of the wealthiest parts of Kobe.

A reputation for keeping disputes between themselves and not harming the families of other mobsters or “non-combatants” long protected them from the ire of citizens and the attentions of the police.

The Yamaguchi-gumi even used to hold press conferences, says Jake Adelstein, author of Tokyo Vice, a book about his experiences dealing with the yakuza as a reporter for the Yomiuri newspaper. “[One] leader wrote a very well-received autobiography, still in print, in which there was also a picture of him serving as the honorary police chief of the day in Kobe.”

Japan’s government has introduced new anti-crime laws in the past two decades that have shrunk the yakuza’s ranks but left much of its organisational power and structure intact. Recent legislation has barred known mobsters from signing real estate contracts, an important source of legitimate income. But the state still has not outlawed membership of a criminal organisation or allowed the use of police telephone tapping, plea bargaining and witness protection.

Partly in an effort to jolt the Japanese government into taking the mob seriously, Washington announced a freeze last year on the US assets of the Yamaguchi-gumi, earned mainly from drug trafficking, money laundering, prostitution and fraud. The sanctions specifically targeted the group’s godfather, Kenichi Shinoda.

Yakuza bosses insist they help keep Japan free of the random street crime that plagues Western cities and that its members operate to a strict set of values that emphasise honour and discipline. But the image has been dented over the years by a string of violent crimes. A recent two-year war in southern Japan resulted in seven deaths and two dozen shootings and bombings.

In a front-page letter in the new magazine, Mr Shinoda urges the gang’s members to stay true to their values, despite the police crackdown.

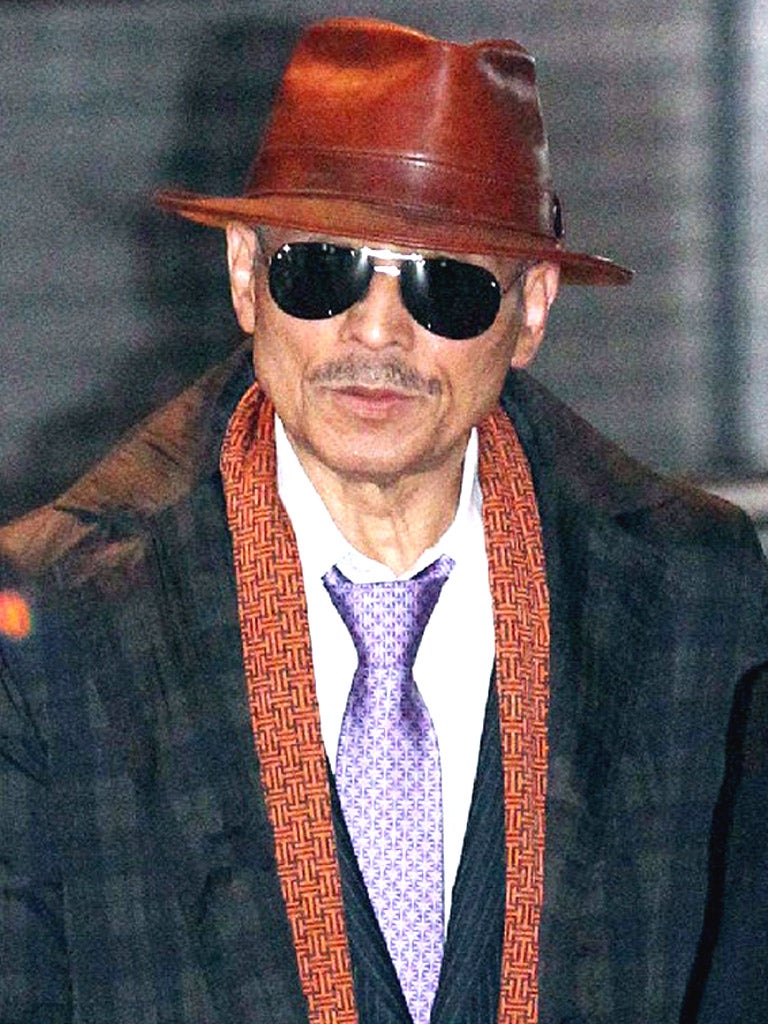

Sword-wielding don: Kenichi Shinoda

Now 71, the thuggish menace of the Yamaguchi–gumi’s godfather has dimmed since he began climbing through the ranks of what is sometimes called the General Motors of crime. Television pictures of Kenichi Shinoda emerging from prison in 2011 after serving six years for gun possession showed a dapper, slightly stooped man sporting a leather fedora.

But appearances are deceptive. In the 1970s, Shinoda served 13 years for killing a rival gang boss with a samurai sword. In the 1980s, he was kidnapped and tortured by rivals. His ruthless leadership of the Koto-kai branch of the Yamaguchi-gumi took it well beyond its traditional territory in western Japan into Tokyo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments