The Big Question: What makes K2 the most perilous challenge a mountaineer can face?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Why are we asking this now?

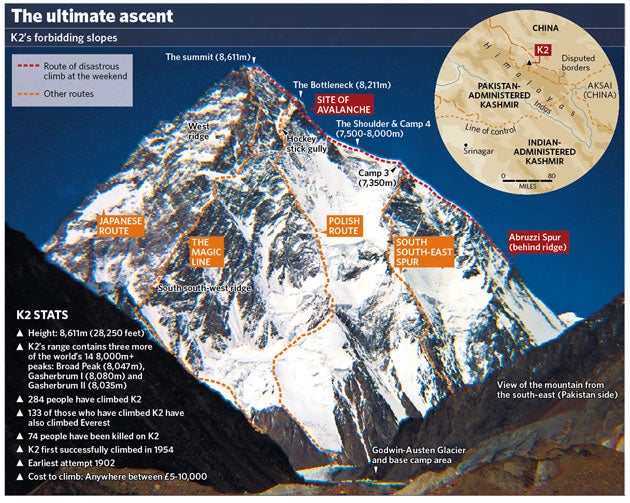

Because at least 11 people are currently missing presumed dead on the notoriously dangerous mountain. Located in Pakistan's majestic Karakoram range, the world's second highest mountain has long been regarded as a dangerous peak to climb, but the weekend's disaster constitutes the largest loss of life in a single day on K2's slopes.

The Pakistani army yesterday managed to rescue two Dutch climbers who were caught up in the mayhem after a gruelling 48 hours stranded on the 8,611m mountain. The men were two of 22 climbers from eight expeditions who attempted to tackle the summit on Friday following a brief lull in the weather. An Italian climber, Marco Confortola, is still trying to make his way down to the 6,000m because the rescue helicopters cannot get any higher in the thin air.

What exactly went wrong?

Initial reports were sketchy but as the survivors came down a clearer picture emerged which pointed towards both a freak disaster and human error. At least nine people were thought to have been swept away by an avalanche after an enormous serac – a large overhanging pillar of ice – broke off the mountain and crashed into climbers on a treacherous part of the final ascent known as "The Bottleneck".

One of the rescued Dutch climbers, Wilco Van Rooijen, said yesterday that people may have fallen to their deaths because an advance rope line was in the wrong place. "We had to move it," Van Rooijen said. "That of course took many, many hours. Some people turned back because they did not trust the rope any more." He added: "On the summit attempt everything went wrong."

Pakistan's ministry of tourism has released a list of 11 missing climbers. It includes three South Koreans, two Nepalis, two Pakistanis and climbers from France, Ireland, Serbia and Norway.

Why is it called K2?

In the mid-19th century the British forces in India began surveying peaks and passes in the Himalayan range in order to keep a watchful eye on any possible route that a Russian army might take if it invaded South Asia.

In 1856 Thomas Montgomerie arrived in the area of the Karakoram where K2 lies and began, somewhat unimaginatively, naming all the major peaks there "K "for Karakoram" plus a number. K2 was the second peak he surveyed. All the other peaks have since been given new names such as Broad Peak and Gasherbrum, but for some reason K2 has stuck. Chinese and Balti speakers usually call the mountain Qogir or Chogori (Big Mountain).

Who first conquered it?

The first successful ascent was made by two Italians, Lino Lacedelli and Achille Compagnoni, on 31 July 1954, but not before a number of climbing disasters had already turned K2 into a legend among the world's mountaineering fraternity. The Italians used oxygen and a large party to tackle the summit along the now commonly traversed south-eastern ridge known as the Abruzzi Spur. An American expedition a year earlier resulted in one of the most dramatic rescues in climbing history when a single climber managed to hold on to five other colleagues who had fallen using nothing more than an ice pick.

And who followed?

No one for 23 years until the second ascent by the Japanese climber Ichiro Yoshizawa in 1977. Since then around 280 people have reached K2's summit – a paltry number compared to the 3,681 who have made their way to the top of Everest. The first woman to conquer K2 was Poland's Wanda Rutkiewicz in 1986. Rutkiewicz died shortly afterwards trying to scale Kangchenjunga (8,586m). The next five women to climb K2 either died on the way down or on their next major climb, leading some to speculate that K2 was cursed for female climbers. The curse, however, has since been broken.

So what makes K2 so dangerous?

"It's enormous, very high, incredibly steep and much further north than Everest which means it attracts notoriously bad weather," says Britain's most celebrated mountaineer Sir Chris Bonnington, who lost his colleague Nick Escourt in an avalanche on K2's western side during an expedition in 1978. In 1986 13 climbers were killed in a week when a vicious storm stranded numerous expeditions.

Although Everest is 237m taller, K2 is widely perceived to be a far harder climb. "It's a very serious and very dangerous mountain," adds Sir Chris. "No matter which route you take it's a technically difficult climb, much harder than Everest. The weather can change incredibly quickly, and in recent years the storms have become more violent. People who have recently been there have told me that the snow conditions are also getting worse."

So what is the secret to a successful ascent?

According to the mountaineering historian Ed Douglas, "You have to be really good and lucky." The problem, he explains, is that although the final day of climbing, from Camp 4 to the summit, is approximately the same as Everest's final day it is steeper and more dangerous, making it physically exhausting. "It's a very long summit day. The climb is technically demanding and even once you get past The Bottleneck there's still a long way to go to the top. You only have to look at the list of those who have died on K2 to see that it contains some very accomplished climbers."

Traditionally most climbers have decided against using oxygen in favour of a light, fast ascent but in recent years cylinders have made a comeback. In 2004 more than half of the 47 summiteers used oxygen.

How does it compare to other mountain challenges?

It certainly ranks as one of the most dangerous mountains in the world to climb. Only Nanga Parbat, another 8000m-plus peak at the western edge of Pakistan's Karakoram, and Nepal's Annapurna have a higher death ratio. It is estimated that 74 of K2's 280 summiteers have died, meaning that 26 per cent of those who reached the top died on the way back down.

The death ratio for Nanga Parbat and Annapurna is 28 per cent and 40 per cent respectively. At least 179 people have died on Everest, but considering how many people scale it every year the likelihood of dying whilst doing so is a relatively small 10 per cent.

Is K2 a challenge too far?

Yes

*A fatality rate of nearly 30 per cent tells its own story

*Pakistani soldiers are regularly forced to risk their lives to rescue climbers on K2

*The explosion in popularity of Himalayan climbing is damaging the local environment

No

*You can't stop the world's best mountaineers having a crack at it

*Equipment and rescue techniques have hugely improved over the past 10 years

*No mountain can ever been considered wholly safe

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments