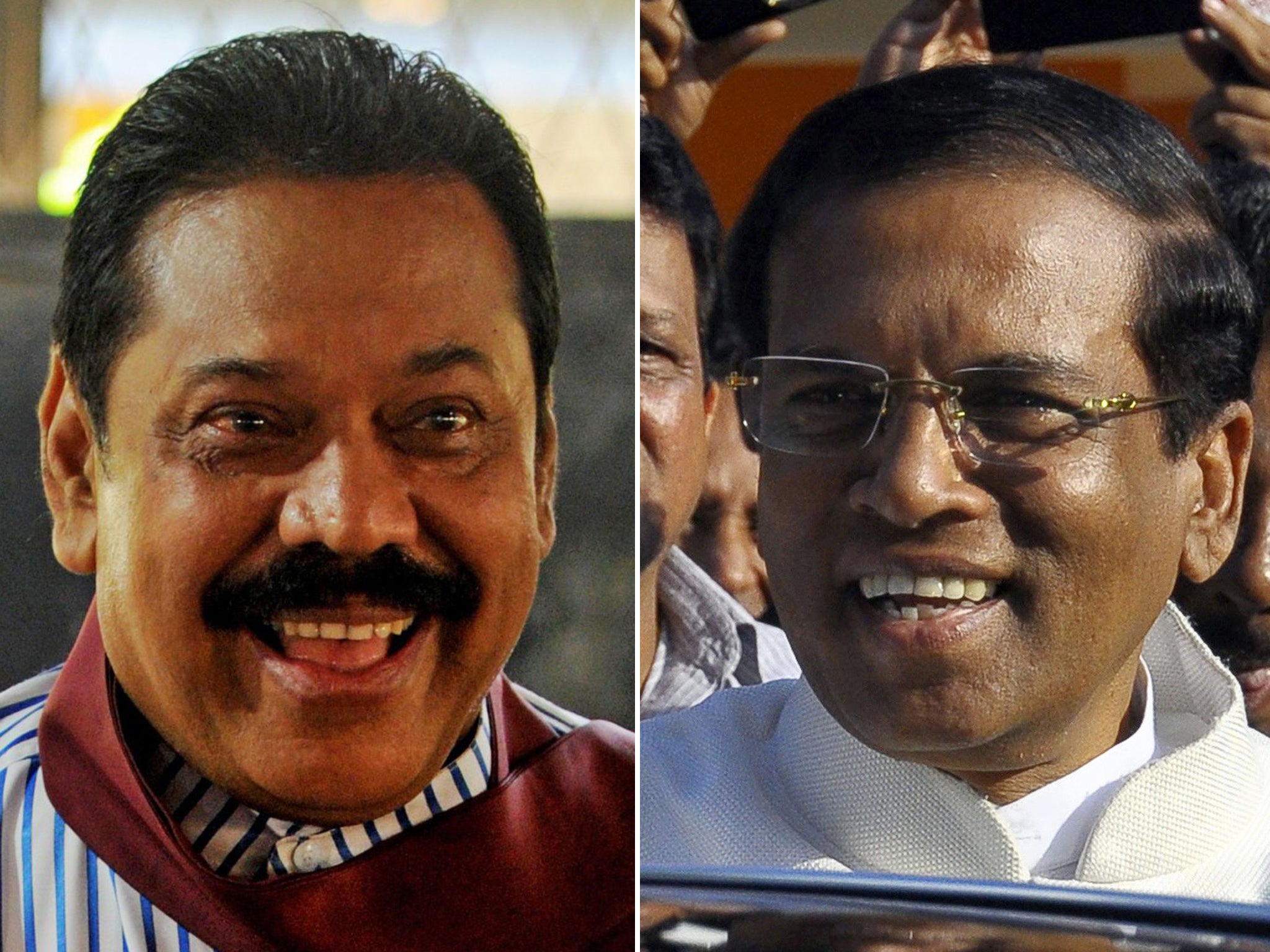

Sri Lanka election: Day of reckoning for a once untouchable president who could suffer an unexpected and humiliating defeat

Mahinda Rajapaksa called the poll two years early, confident of an easy win. But he faces losing power to his former ally, Maithripala Sirisena, who has tapped into discontent over cronyism and costly vanity projects

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Sri Lanka is braced for a major political upset, after a turnout of 75 per cent in the presidential election lent force to speculation that the strongman who ended the civil war, and whose family has towered over the nation in recent years, could suffer a humiliating defeat.

Mahinda Rajapaksa has won the previous two presidential elections, converting the war dividend for ending the 26-year conflict with the Tamil Tigers in 2009 into an unassailable mandate, and marginalising the opposition.

But in using his power to scatter political largesse among his relatives, pursuing absurd and costly vanity projects, trampling on the constitution and cowing the national media into submission, he traduced a democratic tradition which, despite its many failings, has endured since independence. And now – thanks to the defection of a close ally – he could be set to lose everything.

Maithripala Sirisena, tall, thin and bespectacled, mild and scholarly in his demeanour, does not have the aspect of a political attack dog. Anyone further from the moustachioed bulk and braggadocio of President Rajapaksa in his pomp is hard to imagine.

Perhaps Mr Rajapaksa was similarly taken in by the gentle manner of his trusty health minister, number two in his administration, on the night in November when they shared a homely supper of string hoppers, the rice flour pancakes that are a national favourite.

Rude awakening came the next morning when Mr Sirisena announced, less than two months before polling, that he would stand for president against his boss.

“Judas” cried the President. But Sri Lanka is fortunate that Mr Rajapaksa has not been in power long enough to dismantle his nation’s democratic architecture. Mr Sirisena has proved an agile operator. Stepping into a political vacuum – Mr Rajapaksa was expected to make mincemeat of the opposition candidates – he recruited not only the Buddhist nationalists but also the remaining political representative of the 15 per cent Tamil minority to his cause.

Latterly he has also succeeded in wooing both former prime minister, Ranil Wickremasinghe, and former president, Chandrika Kumaratunga, – the two big political beasts of the pre-Rajapaksa era – to his side. The breadth of his support is an indication not only of his persuasive power but also of the extent to which the Rajapaksa hegemony has frightened and estranged the political establishment.

Political analyst Paikiasothy Saravanamuttu said: “Issues of corruption, allegations about the rule of law breaking down completely, lack of transparency and accountability, all of these things… come together in this challenge, mounted almost by the entire… opposition, [with] the Buddhist nationalists at one end and the Tamil National Alliance at the other. That gives you a sense of the breadth and scope of the disenchantment of the opposition.”

This was an election that Mr Rajapaksa brought upon himself, calling it two years earlier than was constitutionally required. Poorer than expected results in local elections last year persuaded him to secure his power while the going was good. On Friday Sri Lanka will learn how good his instincts were – and how deep the discontent which Mr Sirisena has tapped.

The Rajapaksa style has been blunt and assertive from the start. A lawyer by training, born to a Sinhalese political dynasty from the southern fishing port of Hambantota, he brought two of his brothers into government with him and set about bringing the island’s appalling civil war to an end. He succeeded in the goal which had eluded his predecessors in office for a generation: restoring peace. It was a great achievement bloodily achieved, and ensured an avalanche election victory in 2010.

But since then he has acted as if on a never-ending victory circuit: plastering his image on the nation’s bank notes and on billboards, installing close relatives, including a son, a nephew and others in key political roles, in addition to his two brothers. According to one estimate, this resulted in the Rajapaksa family having discretionary control of two-thirds of the nation’s budget.

Wrenching himself free of onerous links to the West and to India, he has made Sri Lanka a key regional ally of China. The Chinese have built motorways and restored some of the island’s rail network; they also built a new airport in Hambantota, where it serves scant purpose. In addition, he signed a deal with Australian tycoon James Packer to build a $400m casino-based resort, to the disgust of more conservative Buddhists, including Mr Sirisena, a teetotal anti-tobacco campaigner.

But in the process of driving the economy forward at 7 per cent growth per year, he has lost touch with his grassroots support, and disgust at the wealth of the First Family and its failure to do anything to improve the lot of the poor has been growing steadily. Likewise, the Tamil minority has been alienated by his refusal to conduct a serious enquiry into war crimes allegedly committed during the massacre that ended the civil war.

Whatever the result, Mr Rajapaksa is, for the first time in more than a decade, on the back foot. “The devil you know is better than the unknown angel,” he told a sceptical crowd in Jaffna.

For his part, Mr Sirisena says: “I came out because I could not stay any more with a leader who has plundered the country, government and national wealth.” All of Mr Rajapaksa’s chickens are coming home to roost. If they are not enough to turf him out of power, his revenge on his enemies, both new and old, may be fierce.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments