Pakistan’s Piccadilly is No 1 Taliban target: The regularity of terror attacks in Peshawar's bazaar leads to citizens questioning their seemingly rudderless leadership

The once-great trading centre is now under siege - with 140 killed in bombings in recent weeks

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

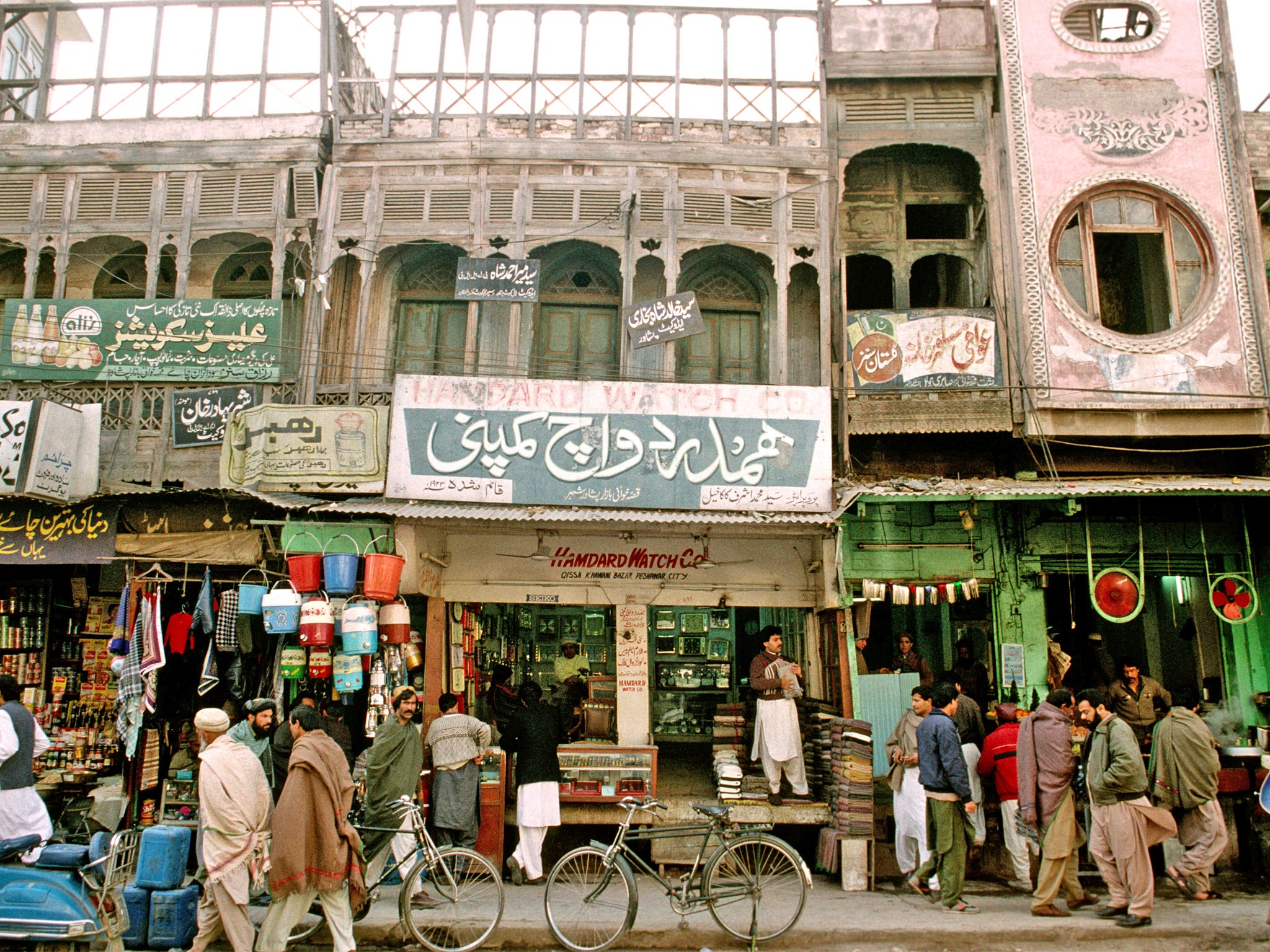

Your support makes all the difference.The Qissa Khawani bazaar in Peshawar’s old city is known as the “marketplace of storytellers”. Local legend has it that invading armies, merchants passing through and other visitors spilling through the Hindu Kush gathered here, in the street between two rows of tightly packed, towering shops, to sip tea and trade tales.

When Sir Herbert Thompson arrived in the city as a magistrate in the 1920s, he was struck by the bustle. “From its waist the city swelled out into its second half which was served by the main gate,” he wrote, “the Kabul gate, at the end of the great shopping centre, the Qissa Khawani bazaar with its rows of matchbox-sized shops.”

Around that time, some of the bazaar’s most famous local residents left the city in search of fame in Bombay. They were storytellers of a different kind. In the Dahkki Nalbandi neighbourhood lived Prithviraj Kapoor, the famed Bollywood actor, whose children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren are some of India’s biggest film stars. Shahrukh Khan’s father lived nearby, as did the actor Dilip Kumar.

Now, the bazaar that was once known as “the Piccadilly of Central Asia” lies deserted. The shopkeepers, who eventually replaced the storytellers, colonial officers and film stars, are left to survey the ruin. Outside a vast electronics store, there is a crater four feet deep. It was created when a car exploded, carrying nearly 250kg of explosives, phosphorus and artillery shells. The nearby mosque is badly damaged, as is the post office across the street.

Naveed Qureshi was sitting in his shoe store across the street when it began to shake fiercely. He went out on to the street to find roaring flames. “And there were piles of bodies, and body parts, everywhere.” At least a dozen shops were destroyed. An entire family of 18 people, shopping for a looming family wedding, was killed.

The deaths of over 43 people in Peshawar last Sunday came just days after two other major bombings in this storied frontier city. Two days before, a bus carrying government employees to the city was bombed, killing 17 people. And on the previous Sunday, Pakistan’s tiny and beleaguered Christian community suffered its worst-ever attack, with over 80 people killed by two suicide bombers.

Faced with this unrelenting assault, the citizens of Peshawar have begun asking questions of their seemingly rudderless leadership. The government of Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif, and the provincial government of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa province (of which Peshawar is the capital), have insisted they want to negotiate with the militants. But as local residents point out, the militants don’t seem interested in talking.

The bazaar is a mere stone’s throw away from the 19th-century All Saints Church. When the bomb went off, the parishioners solemnly sitting in their pews became terrified once again. They thought it was a repeat attack, and let out screams of panic until they realised this time it wasn’t them.

Inside, the clock still says the time is 11:43. It stopped working when the blast happened. In the church’s courtyard, one bomber struck by the steps leading out of the Sunday school, where young children were gathered. Another struck the congregation coming out of the church.

The parishioners of this elegant, domed, Mughal-designed church fear the worst isn’t over. “We’re very worried that there will be more attacks,” says Jamil Naz, a member of the local Christian community. “Imran Khan is talking about letting the Taliban open an office for negotiations. That will be the worst thing.”

If the Taliban are allowed to open an office, adds Mr Naz, “they’ll be given more space to operate. Then there’ll be more attacks.” The city of Peshawar voted overwhelmingly for Mr Khan in the May general elections. They said they wanted change, and were war-weary. This is not the first time Peshawar has been under siege, with militants menacing the city in 2008 and 2009.

But the mood has changed. The shopkeepers of the Qissa Khawani bazaar say that the police came to warn them about an impending attack last Friday. “They said that a car was wandering around,” says Zafar Yab, the owner of a shoe store. The police didn’t offer any protection, Mr Yab recalls, incredulously. They wanted the shopkeepers to protect themselves.

The bazaar has seen much violence before. In 1930, British troops opened fire on a group of non-violent Pashtuns involved in the freedom struggle. The death toll was as high as 400, according to some estimates. Later, the leader of the movement, Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, would remark that an unarmed Pashtun was more threatening to colonialists than an armed one.

In recent years, there have been at least four other bombs set off in Qissa Khawani bazaar. And within the old city that surrounds it, there have been at least a dozen. Sometimes the only mercy for the victims is that there is a well-equipped hospital nearby, the Lady Reading Hospital, named for the Marchioness of Reading in the 1920s.

When an explosion happens, ambulances roar through the narrow streets. But once they reach the Lady Reading Hospital, an elegant compound with manicured lawns, they aren’t guaranteed emergency attention.

As Dr Shiraz Afridi, the director of emergencies, explains, there simply aren’t enough resources to cope with the increasingly frequent bombings.

The “walking wounded,” he says, have to wait. “The people who are near death, or will die soon, and won’t survive, are also separated.” The attention is given to the broad chunk in between: the people who are too wounded to walk and still have a chance at living. It’s one of the busiest casualty wards in the world: they see over 2,000 patients a day. And like the shopkeepers, they speak of dealing with one crisis before bracing for the next.

For the residents of Peshawar, the country’s politicians are failing to grasp the gravity of the threat. “Nawaz Sharif says the Taliban haven’t claimed responsibility,” says Sheikh Yusuf, another shopkeeper with a thick beard and eyes that fitfully bulge with rage. “Fine. But someone else did. And let’s say you want to negotiate with one group, but another keeps bombing you. What do you do then?”

Omar Waraich is a fellow with the International Reporting Project

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments