North Korea 'hydrogen bomb test': Strong words are the only weapons the rest of the world can deploy

The implications of the test are universally bad: for regional security in East Asia, for nuclear non-proliferation, for an Obama administration under fire for foreign policy weakness, and even for China

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.However secretive and isolated, the regime in North Korea has always craved global attention. With its claim to have detonated a hydrogen bomb, it has achieved that – and underlined yet again the virtual impossibility of the US or anyone else halting its nuclear programme.

Whether or not the device was what North Korea claimed it to be, the implications of the test are universally bad: for regional security in East Asia, for nuclear non-proliferation, for an Obama administration under fire for foreign policy weakness, and even for China, the one power with real influence in Pyongyang.

The assumption of Korea-watchers used to be that the programme was a bargaining chip to secure the regime’s goal of a peace treaty with the US to seal its global legitimacy – even if Washington insists there can be no such deal without the North abandoning its nuclear ambitions. But this calculus has changed since Kim Jong-un succeeded his father, Kim Jong-il, in 2011.

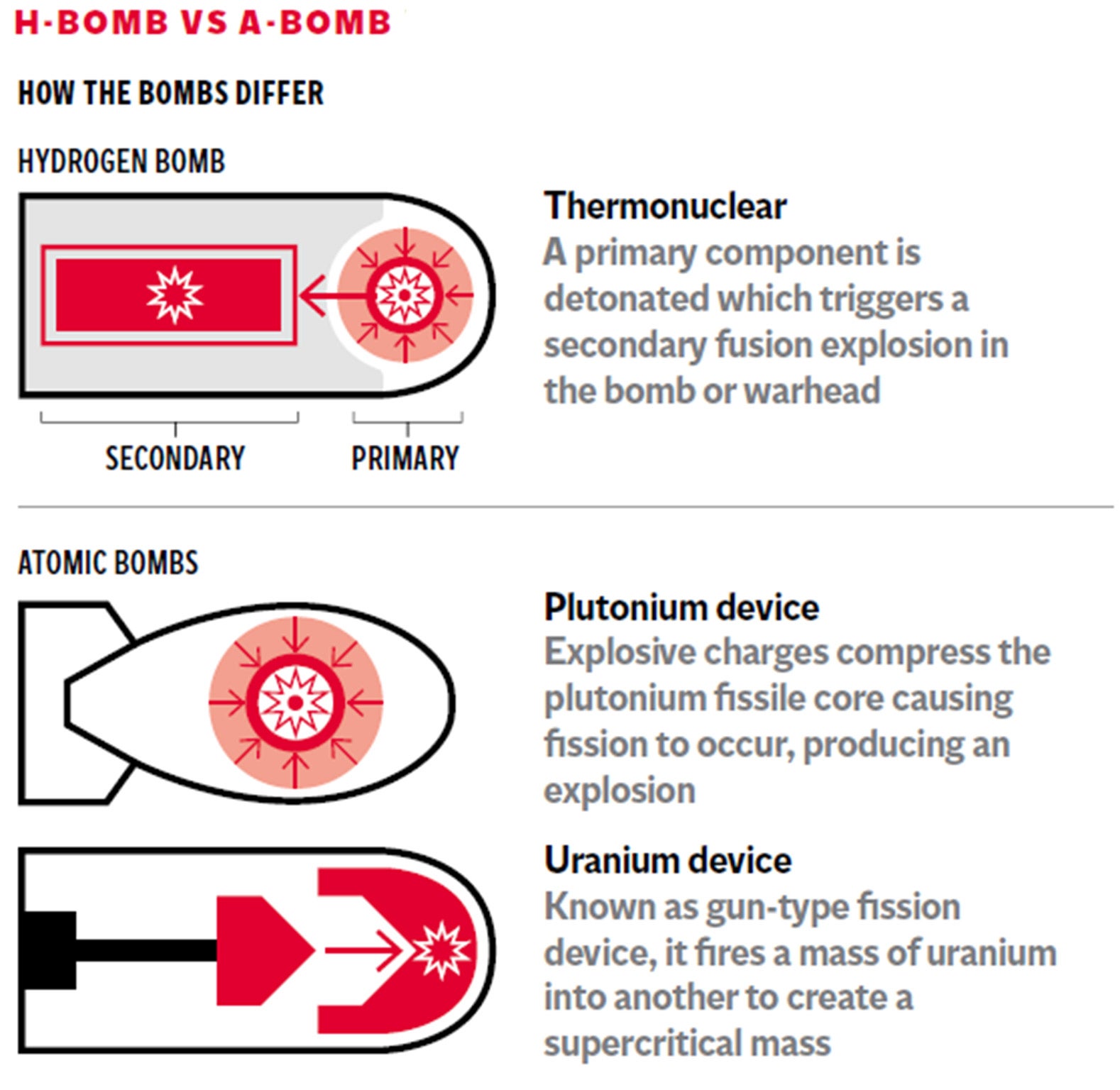

The son is plainly determined to turn North Korea into a fully fledged nuclear power. Whatever the exact type of Wednesday’s test – the North’s fourth since 2006 – Pyongyang is reckoned to have enough plutonium for a dozen nuclear bombs.

And what can the rest of the world do about it? If precedent is anything to go by, very little. Since the North violated the 1994 framework agreement with Washington – the first serious effort to halt its nuclear weapons programme – nothing has worked.

North Korea has rejected Iran-style nuclear negotiations. “Six-party” talks, involving the US, Japan, China, Russia and the two Koreas, have come and gone. Sanctions likewise have failed to bend the North’s will. More UN sanctions are being talked of now, but there is scant chance they will succeed, against a regime historically indifferent to the sufferings of its people, and when the North Korean economy is showing signs of improvement. Military action by the US is unthinkable.

Which leaves China, whose economic support is vital for Kim’s regime. Beijing’s reaction to news of the test was unusually sharply worded, expressing “resolute opposition” and threatening to lodge a formal protest with the North.

And certainly this latest defiance is bad news for Beijing. It is not only a direct rebuff to its attempts to woo its traditional ally by sending a top official to attend a military parade in Pyongyang in October and heaping praise on Kim. The move could also heighten regional tensions, prompting the US, Japan and South Korea to bolster their forces in the western Pacific, just when China is seeking to impose its dominance.

But, as in past crises, China will probably stop short of severe punishment. Beijing does not want instability – and least of all a reunified pro-Western Korea – on its border. A nuclear North Korea is preferable to a North Korea that is falling apart.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments