North Korean nuclear crisis: What's the difference between an atomic bomb and a hydrogen bomb?

Kim Jong-un's refusal to back down on missile testing despite repeated warnings poses difficult questions for international community

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.North Korea claimed that a nuclear blast on Sunday was a big advance from its previous five tests because it had successfully detonated a hydrogen bomb.

But some experts suspect the North may have tested a “boosted” atomic bomb.

How are a hydrogen bomb and a regular atomic bomb different? And why would that matter to the United States and its allies? Here’s what the experts say.

How do nuclear weapons work?

Nuclear weapons trigger an explosive reaction that shears off destructive energy locked inside the bomb’s atomic materials.

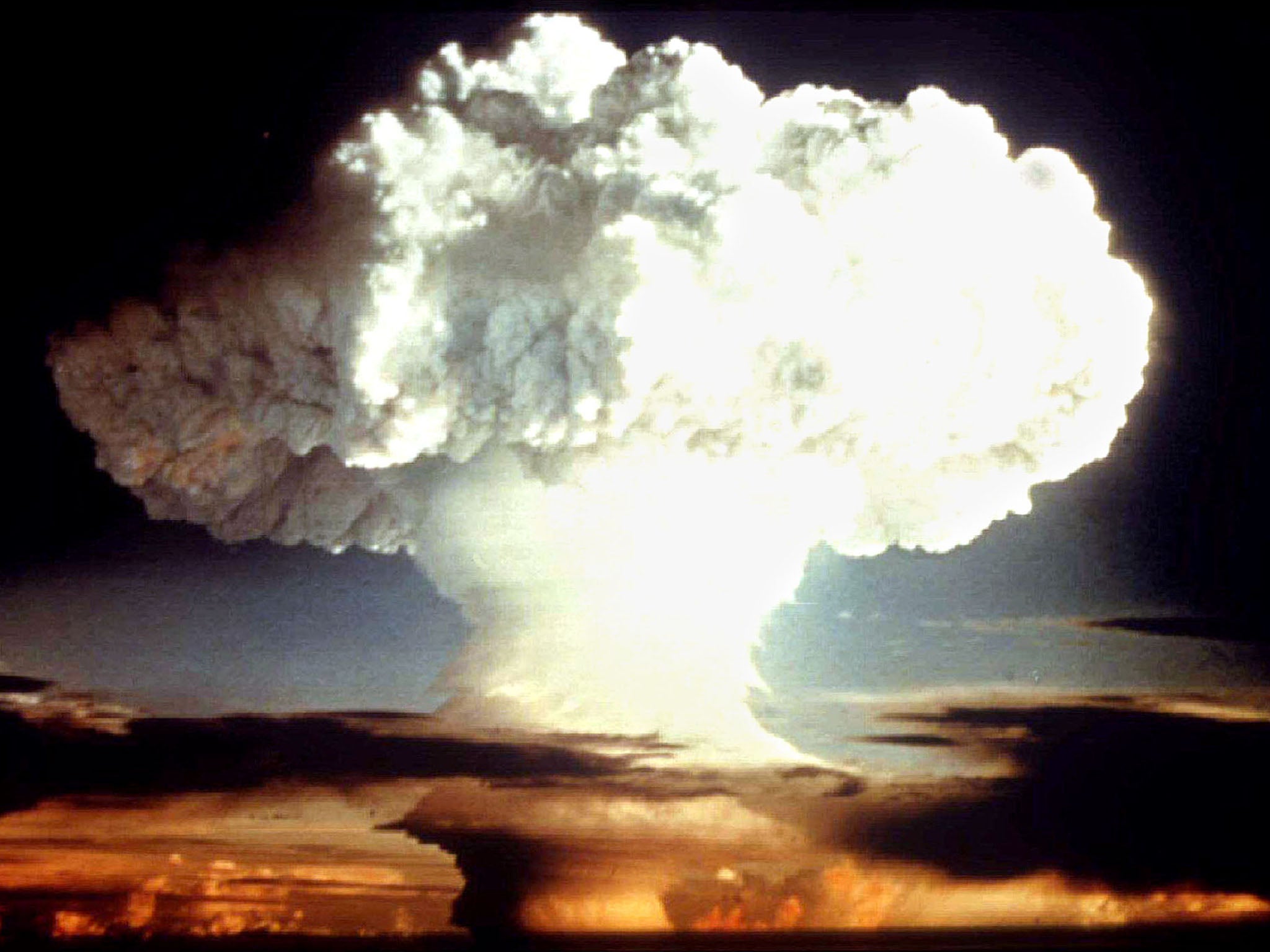

The first atomic weapons, like those dropped by the United States on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in the Second World War, did that with fission — splitting unstable uranium or plutonium atoms so that their subatomic neutrons fly free, smash up more atoms and create a devastating blast.

How is a hydrogen bomb different?

A hydrogen bomb, also called a thermonuclear bomb or an H-bomb, uses a second stage of reactions to magnify the force of an atomic explosion.

That stage is fusion — mashing hydrogen atoms together in the same process that fuels the sun. When these relatively light atoms join together, they unleash neutrons in a wave of destructive energy.

A hydrogen weapon uses an initial nuclear fission explosion to create a tremendous pulse that compresses and fuses small amounts of deuterium and tritium, kinds of hydrogen, near the heart of the bomb. The swarms of neutrons set free can ramp up the explosive chain reaction of a uranium layer wrapped around it, creating a blast far more devastating than uranium fission alone.

The United States tested a hydrogen bomb at Bikini Atoll in 1954 that was more than 1,000 times more powerful than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. Britain, China, France and Russia have also created hydrogen bombs.

What would a successful hydrogen test mean?

North Korea claimed that it successfully staged a hydrogen bomb test in January 2016, but experts were sceptical.

A successful test this time would show that the North’s nuclear program has become more sophisticated and that the country is closer to making an atomic warhead that could be fitted on a long-range missile able to strike the mainland United States.

The underground blast, which caused tremors felt in South Korea and China, was the first by the North to surpass the destructive power of the bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

If the North has the capability to build a hydrogen bomb, it could open the way to making warheads that pack much more destructive power in a smaller space. It could also enable North Korea to enhance the threat from its limited stocks of enriched uranium.

What will experts look for?

Analysts who advise governments on nuclear weapons will study the shock waves from the blast measured by monitoring stations. They will also look for clues from traces of nuclear gases that could float into the atmosphere.

Those traces may tell if this test was really a hydrogen bomb, or perhaps something less than a full-scale thermonuclear device. But it can take weeks for the gases to leak out and be detected.

The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments