Nepal earthquake: Six months on from the country's double cataclysm, the survivors tell their stories

Six months on from the earthquakes that devastated Nepal, its people's famed resilience is being tested once again, with 60,000 in camps unsuitable for the coming winter and others living amid rubble while political infighting delays reconstruction

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference."This is my home," says 66-year-old Panchamani Shakya (right), sitting in a pile of rubble where his house once was – overlooking the once-magnificent, now-destroyed Machhendranath Temple in Bungamati, Nepal.

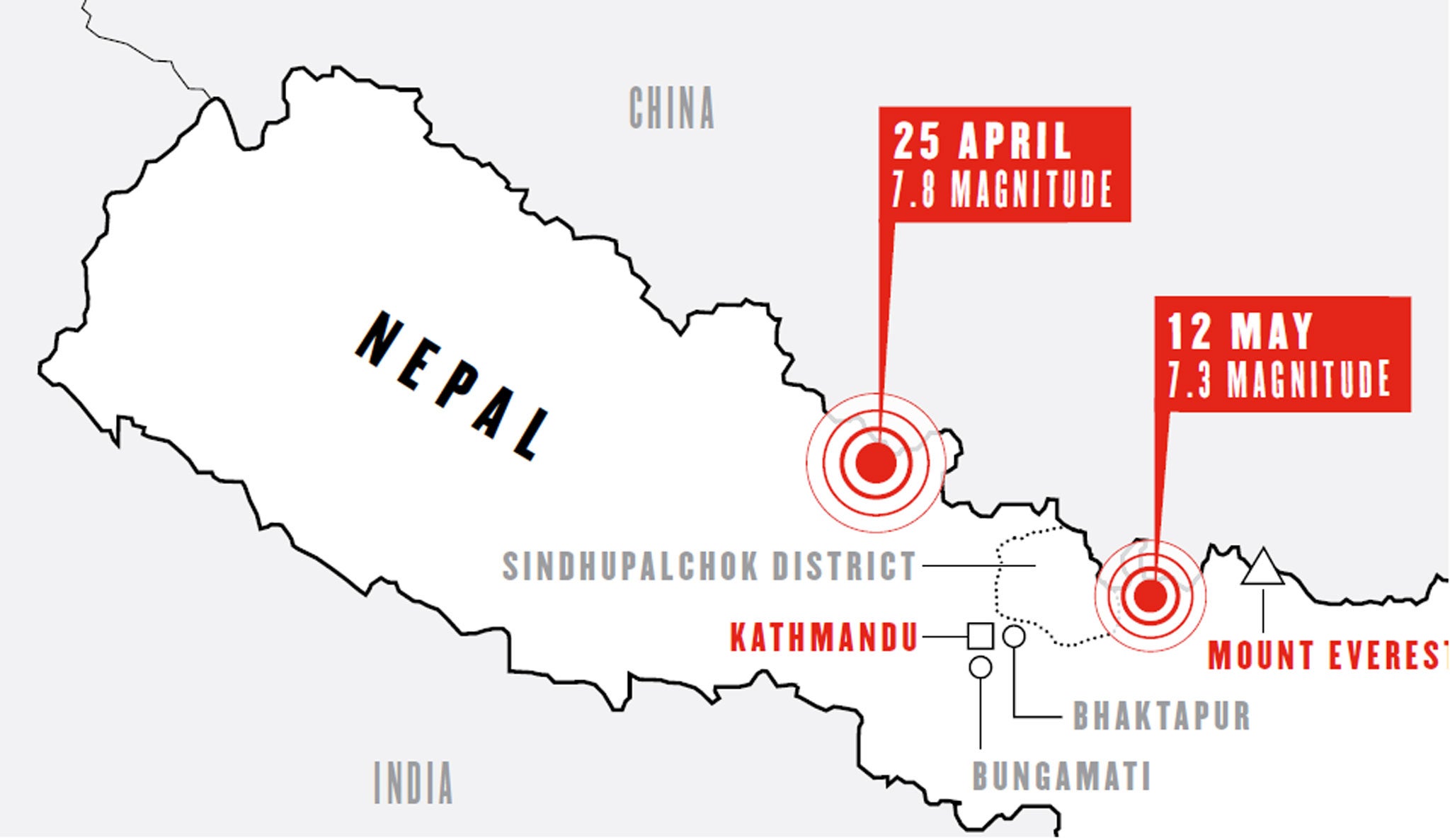

The former farmer is currently living in a temporary shelter following the earthquake of 25 April and major aftershock of 12 May that killed almost 9,000 people and damaged or destroyed almost 900,000 homes.

Shakya has received just 15,000 rupees (£93.50) of the 200,000 (£1,250) promised by the government to rebuild his home and, like many people, remains confused about when and how the remaining money might arrive. Asked why he returns to his home in a square once designated a World Heritage site and which used to bustle with tourists and traders, he replies: "What else is there for me to do?"

It is now six months to the day since the first earthquake, which hit 7.8 on the Richter scale, and which was followed a few weeks later by a 7.3 aftershock. But despite the scale of damage in the country, one of the least developed in the world, Nepal has fallen off the Western news agenda, replaced by the refugee crisis engulfing Europe.

Many towns and villages in the Gorkha region, west of Kathmandu, and in Sindhupalchok, to the east, were destroyed by the first quake, and 60,000 people remain in 120 displacement sites – 85 per cent of which are thought by the UN to be unsuitable for winter.

While the government sent in the army, aid agencies – already running essential nutrition and hygiene programmes in the region, where many children suffer from acute malnutrition – immediately expanded their programmes in the wake of the disaster.

One of those agencies is Action Against Hunger, with whom I travelled to Nepal. It has been operating mental-health services alongside its malnutrition programmes in the south of the country since 2014. Within weeks of the second quake, it took its mental-health provision to the stricken areas as well as organising shelter, cash for work, food and the rebuilding of water points.

The World Health Organisation has noted that people involved in humanitarian emergencies have an increased risk of developing mental-health problems, and Nepal already had one of the highest suicide rates in the world (around four times that of the UK). The national suicide rate increased by a further 41 per cent in the months following the disaster, according to police.

In the capital Kathmandu, 15km from Bungamati, homes were largely unaffected and life is getting back to normal. The main evidence of the quake lies in the damaged Buddhist and Hindu shrines and monuments, though the city retains its visual splendour. Tourism collapsed after the disaster, but trekking routes reopened in September and tourism experts expect 300,000 visitors this year.

Yet only half-an-hour away, towns are reduced to rubble and people are living in canvas tents or metal huts. In Bhaktapur, one of Nepal's most famous historic sites, people are trying to cope among the dust of houses with missing walls and partial roofs. Many say the camps they had been living in were closing down or there was no capacity for them. "There is nowhere else for us to go," one woman tells me. "We have been abandoned by the government," says another.

Some $440m in international aid and charity has been donated to assist Nepal's recovery, but rebuilding has been hampered by monsoon season, and the government has been paralysed by talks about the country's new constitution. The National Reconstruction Authority, set up in June to co-ordinate the work, is not yet properly functioning, while a fuel blockade in the south of the country, triggered by protests against the new constitution, has almost crippled Nepal.

"It will be five years minimum before reconstruction is complete, and this time is critical as these people are living in bad conditions and their health is at stake," says Martin Rosselot, country director at Action Against Hunger. "We're here to make sure the people don't suffer too much in the meantime."

From meeting those affected, it is clear that in areas where the government has failed, locals have stepped in, organising camps, and ensuring children are taken care of. It is in these people that hope for the future lies. Overleaf, four survivors tell their stories.

For more about Action Against Hunger's work in Nepal: actionagainsthunger.org.uk/asia/nepal

The camp organiser

A maths teacher from Tatopani in the Sindhupalchok District, 29-year-old Madan Poudel is a volunteer camp manager of Bode camp, in the Kathmandu valley

"I was climbing a hill near home and telling my friend this is one of the most beautiful regions in Nepal and that with investment in hydropower, it would also be one of the most developed. At that moment, the earthquake struck.

"My first thought was to make sure the village children and my students were OK. I rushed back; some people had died and many others were injured.

"The youth club where I used to volunteer got together to make temporary shelters, and we stayed with the injured for six days before help came to take them to hospital. Aid agencies came but had no medicine to give at first.

"One of the children whose mother died – she is 15 and was one of the brightest kids in my school – became very depressed and stopped talking. I explained to her that it was not her fault and I arranged the funeral. I have not seen her since that day.

"Later, I was rescued by a helicopter and came to this camp. My friends and I then used trucks and drove four hours back to rescue people from our region.

"As camp manager, I ensure children don't miss school and I supervise homework club. We make sure everyone has food, which is delivered by aid agencies, and that their health and mental wellbeing are OK. We also make sure the latrines are working.

"The camp is closing in a few days, but people have learnt a lot about the importance of hygiene, how to take care of children, awareness about mental health and parental responsibility.

"After the camp closes, I'll stay to clear the area and then I plan to go back to my district and help people who need support. I lost my parents when I was a child, so I don't have family of my own.

"People have lost their homes and family members, but here they were taken care of and the children made friends. When they go home, they don't know what they will find and they will need help. My school has been destroyed – when it is rebuilt I hope the head teacher will call me back to teach there again."

The hospital president

In 1997, businessman Shyam Dhaubhadel, 63, founded the non-profit Siddhi Memorial Foundation in Bhaktapur, offering free primary healthcare to women and children, in memory of his son, who died at the age of four. The town of Bhaktapur was partially destroyed in the earthquake

"On an average day, we used to see 100 mothers and babies at the hospital. But after the two earthquakes, thousands of people were treated here. Many were brought in on their last breath; 48 people died in our garden. But we gave many homeless people shelter and fed 300 to 400 people daily for three to four months.

"After the second earthquake, everyone was in shock. Adults didn't know where to run, let alone children, and mothers who had just given birth were really in panic as they were so vulnerable. Nobody wanted to be treated upstairs, so everyone went into our courtyard.

"When something like this happens you can sit idly by and just pray to the gods to help, but I strongly believe that if you dare to do something to help yourself and your community, then help will come [from outside], and we have received a lot of support at the hospital. However, with the current fuel crisis, if we do not get fuel, we will have to close.

"Children in particular have been affected by the earthquake. They are traumatised just by the mention of the word and many cannot sleep. Around 35 per cent of mothers at the hospital have had counselling, organised by Action Against Hunger, to help them cope with what happened. They also get breastfeeding and hygiene advice.

"My daughter is a doctor and has trained in India in hospital management. She will take over the hospital in the future.

"We would not have opened this hospital if our son had not died – so it has meant we have helped thousands of children because of him."

The evicted family

Forty members of the Tamang family, who come from the remote Baruwa village in Sindhupalchok District, have created a small carpet factory within Bode camp. Among them are Damay Singh Tamang, 46, pictured below with his wife and their daughter

"I was at home with my family when the first earthquake hit. My son and I ran out, but we didn't realise my wife was sleeping; we went back in and she had been buried in the rubble. We managed to pull her out but her legs have been damaged and even now she has pain and can't walk very well.

"We stayed in our village until the second quake – it destroyed everything. In our village, 30 per cent of the people were killed and we have lost many members from our extended family. Before the earthquake there were a lot of aid agencies there, and it was starting to become a model village. Now there are no shops and no food.

"I have been working in the carpet industry for 15 years. We used to weave carpets in our own homes, but we cannot now find a private rental home, as landlords do not want to rent to us, because we weave carpets late into the night and they do not like the noise. Here we are all working together under one roof.

"We are now being forced to leave this camp, as it is a private camp and is closing, so we have to go back to our village. We have no idea what we will find. We will have to walk part of the way, three or four hours, as the road has been destroyed. We will assess the situation and try to make a plan.

"My wife is very worried about the future and what we will find when we return home, but we have nowhere else to go.

"We have received the first 15,000 rupees from the government. This has been given to all families whose homes have been destroyed, but the total due is 200,000, and we don't know when we will get that. But what we also need is training on how to rebuild our homes in a way that will better withstand a future earthquake."

The matriarch

From Tatopani in Sindhupalchok District, Kaili Maya Sherpa, 57, is living in Upper Thali camp in the Kathmandu Valley with her family, including four sons, a daughter and her pregnant daughter-in-law and five-year-old grandson. She was identified in group sessions organised by Action Against Hunger as having need for one-to-one counselling

"I was on my way to a special prayer ceremony when the first earthquake hit, so I believe that God protected [our family], as we were all safe.

"There were 46 houses in my village before the earthquake and only three or four are still standing. There is a constant threat of landslides, so we cannot go back there.

"We were in other camps before reaching this one. This land belongs to a school and they have not asked us to leave yet. We do not know when we will be able to return home.

"We have all the basics here to survive but I have been very afraid for the future and for my children. I was always crying. I had given up all hope. When I would talk to somebody, I would find myself drifting away. I could not sleep and I had stopped eating. All I could do was sit and think about the first and second earthquakes. I really thought that we would all die.

"I attended group sessions with Action Against Hunger and they offered me one-to-one counselling. It was the first time I was able to talk to somebody, other than a family member, who would listen and understand how I was feeling. This has enabled me to start to have hope for the future again. I started eating again. I feel that my mental state is much better and I am beginning to have some confidence in our future."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments