Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty: Rough justice draws a line of sorts under Cambodia’s dark age

Life sentences for two elderly Khmer Rouge leaders represent a kind of closure, four decades on, for the horrors of the ‘killing fields’. But, asks Andrew Buncombe, is it enough?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

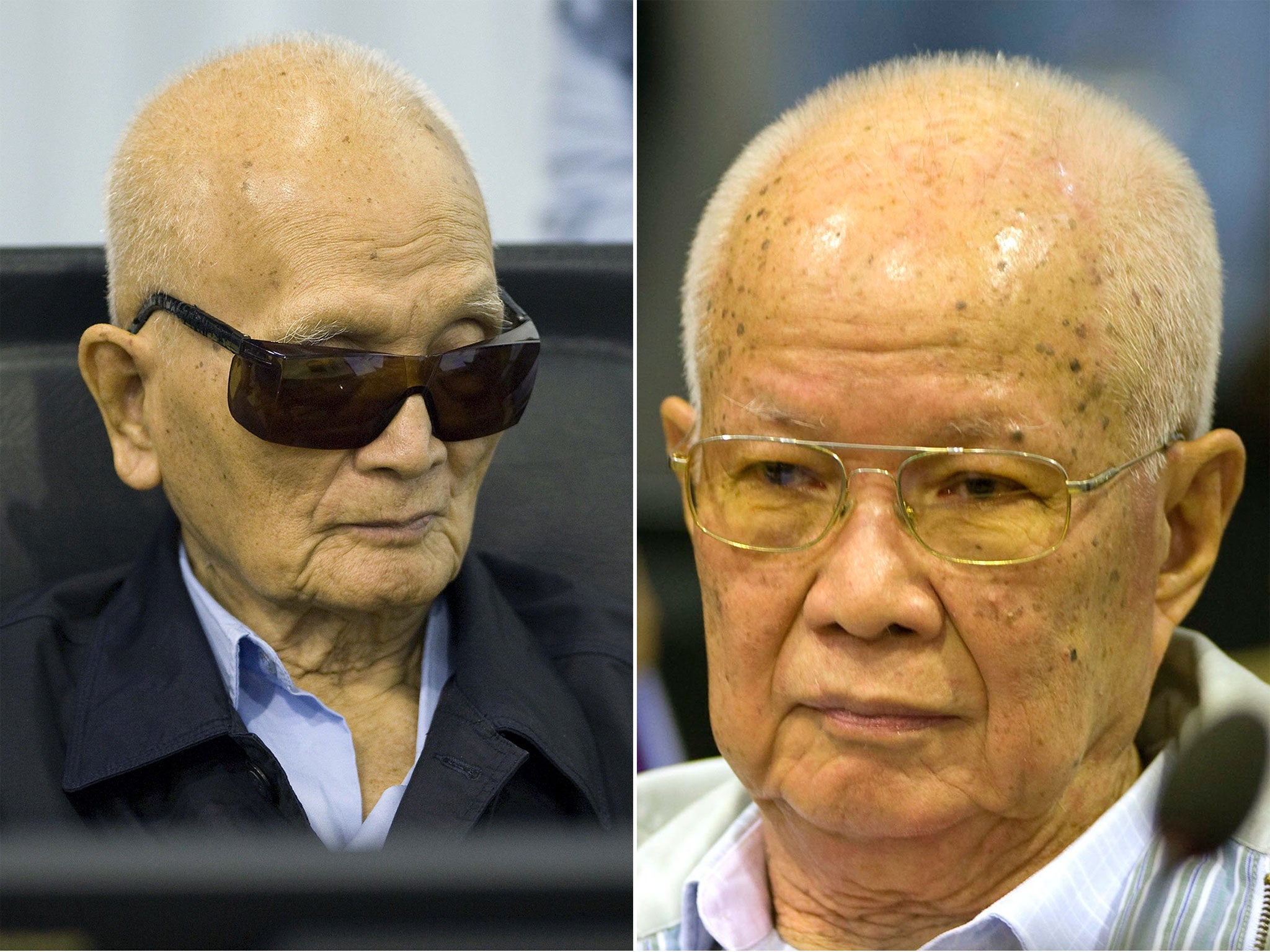

Your support makes all the difference.One of them was too frail to get to his feet for sentencing. The other stood, stony-faced, listening on headphones as the court’s decision was read out. Yet no matter how old they were, no matter how long ago the crimes they were accused of had taken place, today the Khmer Rouge leaders Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea could not escape justice. The pair were found guilty of crimes against humanity and sentenced to life imprisonment.

“The trial chamber has considered the gravity of the crimes of which the accused have been convicted,” declared the chief judge Nil Nonn, during proceedings that were televised across Cambodia. “The chamber sentences the accused Nuon Chea to life imprisonment. The chamber sentences the accused Khieu Samphan to life imprisonment.”

The UN-backed court was told that Khieu Samphan, the 83-year-old former head of state of the Khmer Rouge, and 88-year-old Nuon Chea, its main ideologue, had enjoyed senior positions within the Maoist-inspired regime that in April 1975 seized control of Cambodia and set it on a dark, murderous course. Up to 1.7 million people were bludgeoned to death in the “killing fields”, or else were worked or starved to death.

While the pair were not guilty of every allegation levelled at them, the court said, they were responsible for “extermination encompassing murder, political persecution, and other inhumane acts comprising forced transfer, enforced disappearances and attacks against human dignity”.

The two men, who had said they were not guilty, were asked by the judge to stand to their feet as the judgments were delivered. But Nuon Chea claimed he was unable to do so. Instead, he sat in a wheelchair, wearing a black jacket and with dark glasses covering his loose-skinned face as proceedings played out.

The appearance of the two men at the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia, located on the outskirts of Phnom Penh, is part of an internationally backed process to try to secure justice for those killed during the four years the Khmer Rouge controlled the country between 1975 and 1979.

Four years ago, Kaing Guek Eav, also known as Comrade Duch, who oversaw the Tuol Sleng jail torture and interrogation camp in Phnom Penh, was found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity. A court has ordered that he spend the rest of his life in jail.

Yet the tribunal process, which has cost upwards of £120m, has been persistently dogged by controversy and difficulties. Cambodia’s Prime Minister, Hun Sen, himself a former Khmer Rouge officer, has always objected to the process and has acted to ensure only a limited number of suspects were ever considered for trial.

In addition to Comrade Duch, four other elderly former Khmer Rouge leaders were initially charged. The former Foreign Minister Ieng Sary died in 2013, while his wife, Social Affairs Minister Ieng Thirith, was deemed unfit to stand trial as a result of dementia in 2012. The group’s most senior leader, Pol Pot, died in 1998.

That left just Khieu Samphan and Nuon Chea. Khieu Samphan has acknowledged that mass killings took place during the regime’s rule. But testifying before the court in 2011, he claimed he was just a figurehead who had no real authority.

Nuon Chea, who was known as Brother No 2 for being Pol Pot’s deputy, had also denied responsibility, testifying that Vietnamese forces were responsible for killing people and not the Khmer Rouge.

The two men now face a second trial, due to start later this year, where they will face charges of genocide. That process could take years. Investigators have also examined evidence against a further five suspects, known as cases 003 and 004, but it is unclear whether they will ever reach the trial process. Many observers are sceptical.

Reaction to the tribunals in Cambodia has been mixed. Those who lost relatives or else suffered themselves, have largely welcomed the verdicts. Yet Cambodia has a very young population – more than half are younger than 25 – and many have little knowledge about the Khmer Rouge or that episode in the country’s history.

“I think it is significant. Even though there have been problems I think that in 10 years people will look back and think at least the trial was held,” said Virak Ou, whose father was killed by the Khmer Rouge and who heads the Cambodian Centre for Human Rights. “I think it will help create interest, especially among young people.”

Hundreds of people who had survived the regime’s agricultural labour camps and killing fields travelled to Phnom Penh to witness the verdict.

“The crimes are huge, and just sentencing them to life in jail is not fair,” 54-year-old Chea Sophon, who spent years in a labour camp, told the Associated Press. “Even if they die many times over, it would not be enough.”

Legal campaigners, aware of the difficulties the tribunal has faced, also welcomed the decision.

“Nearly 40 years after some of the 20th century’s most appalling crimes were committed, the victims have seen the perpetrators brought to account before a court of law,” said James Goldston of the Open Society Justice Initiative, which has monitored the tribunal since it was established. Not everyone was impressed. Critics of the tribunal have said the way the cases have been drawn up and the limited time-scale being examined meant the context for the crimes has been largely overlooked. A number of historians, for instance, believe the US bombing campaign in Cambodia and Laos, directed against Khmer Rouge and North Vietnamese forces, had a brutalising effect on the broader population and built support for the rebels.

Similarly, the support given to the regime by China, and the Cold War-era decision of the US and Britain to support the Khmer Rouge in retaining Cambodia’s seat at the UN General Assembly even after they had been defeated, was not examined.

“I think an argument could be made that the very way the tribunal was founded means [these issues] were not looked at,” said Michael Karnavas, a lawyer who represented Ieng Sary before his death.

“Nuon Chea kept saying, ‘You are only looking at the crocodile’s body and not its head and tail’. That is a good analogy. You are only interested in snippets.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments