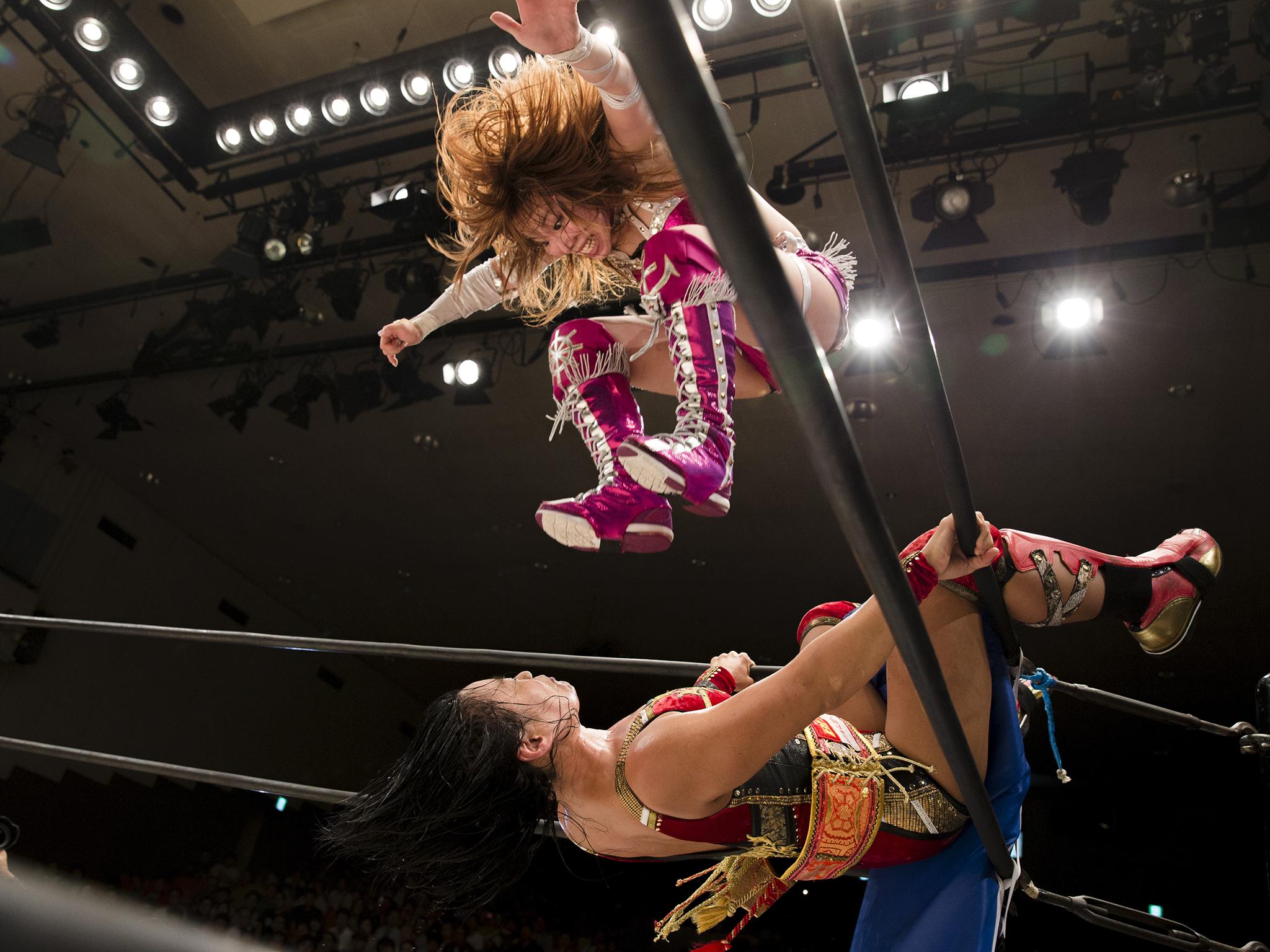

Japan's women wrestlers fight to win

Forget cherry blossoms and delicate slices of raw fish

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Japan on which Kris Hernandez has pinned her dreams is the thud of body slams, sweat, and garish costumes – the world of professional women's wrestling.

“I fell in love with it – the drama, the excitement,” the 31-year-old American said of her first encounter with this unusual side of Japan.

“I was on the edge of my seat with every move, thinking 'Oh my God, how come they are not dead? Can I make a living doing this? Let me try'.”

So Hernandez, who lived in San Francisco before coming to Japan, became the first foreigner to train from scratch and work her way up into Japanese women's pro wrestling.

She quit her teaching job and shared a house with women wrestlers, living off savings as she began a tough daily training regime including gymnastic moves.

“I was pretty poor then, but I wanted to become a wrestler so badly.”

“I would walk four hours across Tokyo to get to practice, do three-hour training and then get the train back,” she said.

“If I saved the train fare one way, it would be all right.”

She made her debut in August 2014 under the name Kris Wolf, wearing a costume with a wolf's head and tail.

Even in this world, which Hernandez says is harder-hitting than its U.S. counterpart, Japanese rules on hierarchy come into play.

“It's kind of militant – don't talk to the senior unless you are spoken to, clean, stay after until all the seniors leave, then you can leave. Arrive 30 minutes before the seniors,” she said.

The money is not huge – she earns $250 for a weekly show - but that's not the point.

“I was doing it because it was cool,” said Hernandez, who is now on a break after suffering a concussion.

The brutal reality of the ring is masked by a strong fantasy element that feeds its popularity with fans, most of them men.

But the rough and tumble may also be an outlet for many of the wrestlers in a country where women are usually expected to be demure and cute, Hernandez said.

“Sometimes it's a part of themselves that they cannot normally express,” she said.

“I have met so many that are so sweet and shy outside the ring, and then you get into the ring and they explode.”

Reuters

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments