Indian father hires assassins to kill daughter’s husband because he was from lower caste, court claims

Influence of age-old caste system remains pervasive in modern India

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.They were young, glamorous and dreamily in love.

Pranay Perumalla strode into the wedding hall in a midnight blue suit, his face lit by a grin as he clasped the hand of his bride, Amrutha Varshini. The couple draped huge garlands of flowers around one another’s necks and relatives threw grains of yellow rice that caught in their dark hair.

But even as they celebrated, they were already in danger.

One bright afternoon less than a month later, the couple left a doctor’s appointment in the small southern Indian city where they grew up. A man came up behind them carrying a large butcher knife in his right hand. He hacked Pranay twice on the head and neck, killing him instantly.

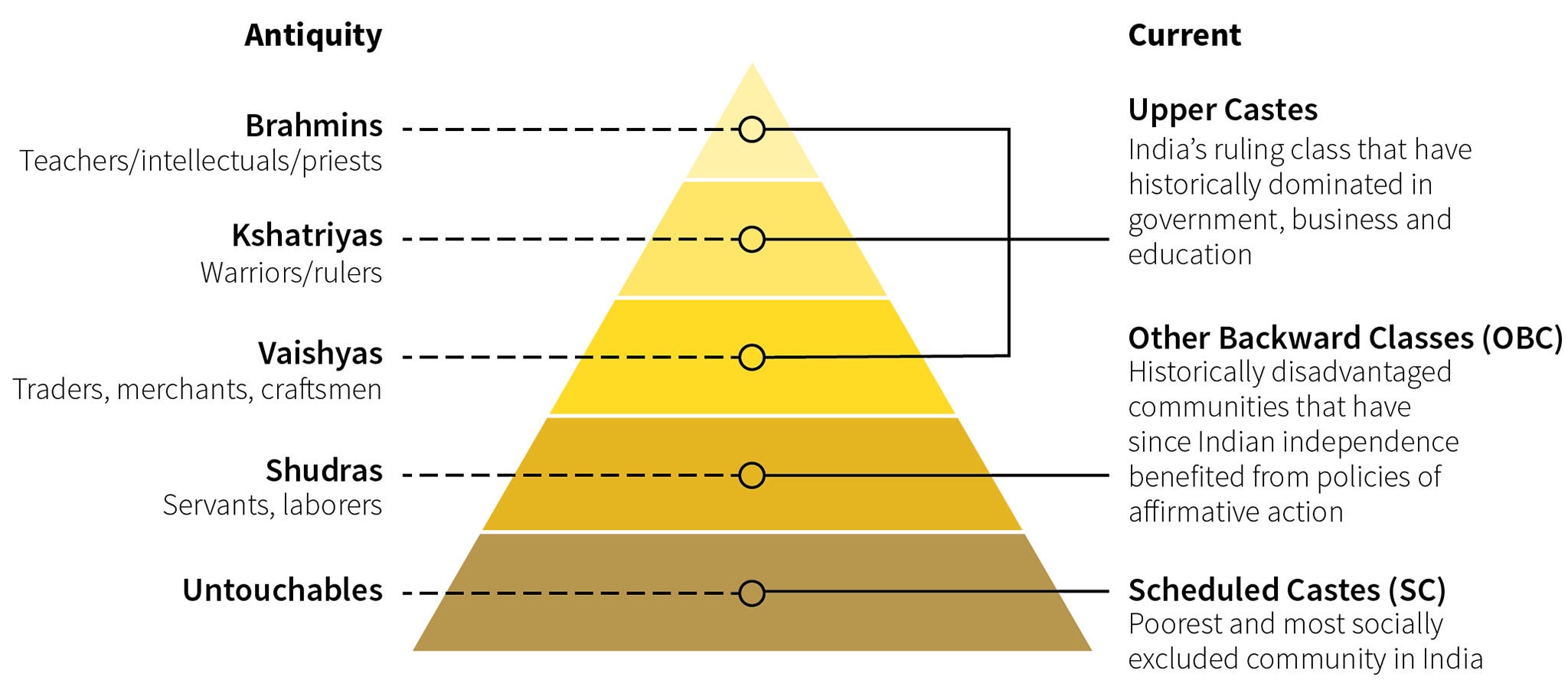

Pranay, 23, was a Dalit, a term used to describe those formerly known as “untouchables”. Amrutha, 21, belongs to an upper caste. Her rich and powerful family viewed the couple’s union as an unacceptable humiliation. Her father, T Maruthi Rao, was so enraged that he hired killers to murder his son-in-law, court documents say.

While Indian society is changing, it is not shifting rapidly enough for couples like Amrutha and Pranay, whose marriage defied an age-old system of discrimination and hierarchy.

Even as India has lifted millions out of poverty, increased education rates and built one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, the influence of caste – a social order rooted in Hindu scriptures and based on an identity determined at birth – remains pervasive.

That system is at its most resilient in marriage. A 2017 study found that just 5.8 per cent of Indian marriages are between people of different castes, a rate that has changed little in four decades. The results surprised the researchers, who had expected to see “more intermingling of the different castes,” says Tridip Ray, a statistician and the lead author. “Unfortunately, that’s not happening.”

In India, transgressing such boundaries sometimes provokes violence. Since late June, killings of men and women who married outside their caste have been reported in the states of Gujarat, Tamil Nadu, Madhya Pradesh and Andhra Pradesh. The daughter of a politician from India’s ruling party recently posted a video on social media seeking protection from her father after she married a Dalit man against her family’s wishes.

Such violent reprisals are “passed off in the name of tradition and honour,” says Uma Chakravarti, a renowned historian and expert on caste and gender. But the motives go far deeper, she says. If a woman can choose whom she wants to marry – including a Dalit man – it “destabilises the entire system” that perpetuates inequality.

On a recent morning, Amrutha – a slim young woman with a heart-shaped face – sat in the living room of the house she shares with Pranay’s parents. Next to her was a screen showing images from closed-circuit cameras: the front door, the street, the corner where a large mango tree towers over the home. Her son, a plump 6-month-old with his father’s smile, sat on her lap.

The house sits near the edge of a Dalit neighbourhood and represents the middle-class stability won by Pranay’s father, Balaswamy, who has worked as a clerk at the Life Insurance Corporation of India for the past three decades. Amrutha grew up a five-minute drive away in a large building owned by her father, a wealthy real estate developer in this city of 100,000 surrounded by rice mills in the state of Telangana.

Dalits, who make up almost 17 per cent of India’s population of more than 1.3 billion, are at the bottom of India’s caste hierarchy. After centuries of subjugation, they have made inroads into politics, higher education and business, partly through affirmative action.

But as Pranay and Amrutha’s story shows, a modicum of upward mobility does not mean they can marry whom they want or live where they want. They continue to do India’s most stigmatised and dangerous work. They face discrimination in the job market and huge hurdles in owning land.

India has “given one person one vote”, says Paul Divakar, general secretary of the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights. But it has not “given each human being the same value”.

When Amrutha started high school, her parents told her not to make friends with girls from lower castes, particularly Dalits, who are officially referred to as Scheduled Castes. Amrutha’s family are Arya Vysya, a group that is part of the Komati caste, traditionally a trading community.

The complexities of the Indian caste system were far from Amrutha’s mind when she went to a movie in the ninth grade with a group of friends. She recognised Pranay from school, where he was a year ahead of her, jovial and athletic. Afterwards, they started texting and talking over the phone.

Their growing friendship had immediate consequences. When Amrutha’s father found out, she says, he beat her for the first – but not the last – time. He took away her mobile phone and laptop and moved her to a different school. Over the next six years, Amrutha and Pranay would see each other only briefly on a handful of occasions.

For Amrutha’s father, the marriage of his only daughter was an obsession. “I can even marry you to a beggar who belongs to an upper caste,” Amrutha remembers him telling her. “But I don’t want you to marry from a lower caste, whoever it is.”

When the two were in college – Pranay pursuing an engineering degree and Amrutha studying fashion – she became frightened that her parents were manoeuvring to marry her to someone else. She got word to Pranay that she wanted to elope.

On 30 January 2018, when her mother went for a midday rest, Amrutha picked up a backpack she had prepared. It contained a cream-coloured dress she had received for her birthday, her school certificates and her identity card. She went down the stairs to the street, where Pranay was waiting, just as he had promised.

Amrutha and Pranay were afraid, but they had a plan. They submitted their applications for passports and studied for an English proficiency test. They hoped to go to Australia and perhaps realise Pranay’s dream of starting a business – a fashion studio or even a dairy farm.

The couple had married in the presence of only a few friends at a temple in Hyderabad run by the Arya Samaj, a Hindu reformist group known for its openness to inter-caste unions. About five months later, Amrutha discovered she was pregnant, so they postponed the idea of leaving home. They also decided to organise a reception to celebrate their marriage.

Hundreds of people attended the festivities on 17 August 2018, but Amrutha’s parents were notably absent. Rao, her father, had already begun to plot Pranay’s murder, court documents say. The month before, he agreed to pay $150,000 (£124,000) to have his son-in-law killed, using a local political leader as an intermediary. Rao, 57, passed along a photo of the pair from their reception invitation to make it easier for the killers to identify Pranay, the documents allege.

On 14 September, Amrutha, Pranay and his mother Premalatha were leaving Jyothi hospital after an appointment with Amrutha’s obstetrician. In video captured by a closed-circuit camera, the couple looked relaxed as they chatted and strolled towards the street. The killer walked up behind them and struck two blows. The video shows Amrutha raising her hands to her head in shock and confusion, then running, crying, back to the hospital for help.

Before she fainted, she called her father. “Somebody attacked Pranay,” she says. “What did you do?”

The murder divided Miryalaguda. Hundreds of people, mostly Dalits, came to the home of Pranay’s family after his death to extend their support. They discussed installing a small statue of the young man to memorialise him.

But others rallied to the cause of Amrutha’s father. “The murder happened because their love started when they were in ninth [grade], and he was killed because their love was not endorsed,” says Bhupathi Raju, honorary president of the Arya Vysya Association in the nearby city of Nalgonda. He formed a “Parents Protection Association” and gathered hundreds of people to visit Rao while he was in jail.

A lawyer in Miryalaguda, Shyam Sunder Chilukuri, formed his own similar group. “This is an incident where a [Scheduled Caste] guy intimidated her and married her,” he says. “There is a chance that other daughters of well-off people would be trapped in the name of love” by what he called “miscreants”.

Chilukuri says his group was not formed to support Amrutha’s father. He paused for a moment. “Do you want to meet him?” He picked up his phone and called Rao, who is out on bail pending the start of his trial, which is expected to begin by September.

Amrutha’s father was around the corner at a small cafe. A short, paunchy man with a moustache and gold-rimmed glasses, Rao sat down briefly with a reporter at a small plastic table but declined to speak on the record, citing legal advice. His lawyer, Ravinder Reddy, declined to comment. In the 56-page main charging document, police cite overwhelming evidence linking Rao to the murder and say he confessed to the crime on 30 September.

AV Ranganath, the superintendent of police for Nalgonda district, says the politician who acted as a middleman between Rao and the killers had inadvertently activated the automatic call-recording feature on his Android phone. Such recordings will be “quite helpful” in court, Ranganath said.

Pranay’s father Balaswamy, 53, says the family wants to see Rao punished to deter future such killings. As he spoke, he cradled his grandson Nihan in the crook of his arm, holding the baby’s chin with one hand to better plant an affectionate kiss on his cheek. Balaswamy can be seen using the exact same gesture for Pranay in a video taken during his son’s wedding reception less than a year ago.

When it came time to deliver the couple’s baby, the family decided that for safety reasons it was better to go to a hospital in Hyderabad, a major city three hours away. But when the family sought a temporary apartment there, Balaswamy says, several landlords declined to rent to them after learning they were Dalits. Caste discrimination is something “we are facing regularly”, he says.

Amrutha says Pranay’s parents are now like her own. “My father was the reason for his death,” she says. But Pranay’s parents “know how we loved each other”.

© Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments