India's dirty laundry: The murder tearing Indian society apart

The murder of a teenage girl in Delhi, unjustly blamed on a domestic servant, has heightened hatred and suspicion at the heart of Asia's most class-riven society. Andrew Buncombe reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.For police in the eastern suburbs of Delhi it seemed like an open and shut case.

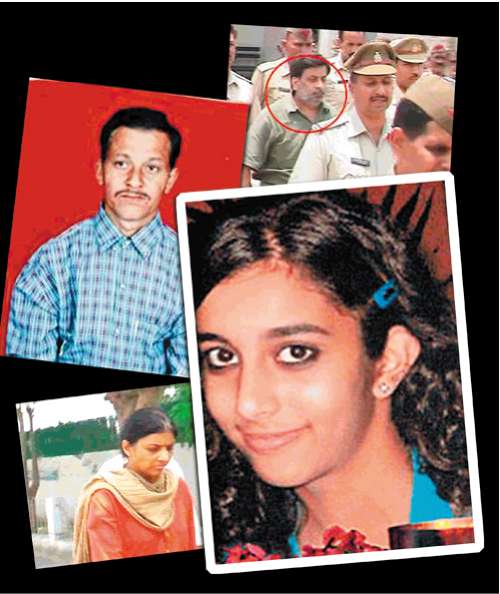

When the body of 14-year-old Aarushi Talwar was discovered in a pool of blood, her throat cut and the family's domestic servant nowhere to be found, detectives had only one suspect. Senior officers said they even had clues as to where the 45-year-old Nepali servant might be hiding and said that a team of officers was being dispatched to Nepal to track him down. The police saw no reason to bring in sniffer dogs, photograph the crime scene or even force open a locked door that led to a terrace despite the presence of drops of blood on the steps.

An immediate media frenzy erupted. The TV channels and newspapers were full of lurid details and unquestioningly blamed Yam Prasad Banjade, also known as Hemraj, the missing servant, for the grisly killing of the teenager. And then one day later, someone opened the terrace door and discovered Hemraj's decomposing body lying on the floor. He too had been murdered, in the same way as Aarushi. Police were forced to reopen the murder mystery.

The authorities' handling of the high-profile case – Aarushi's father, Rajesh Talwar, a dentist, is currently the police's latest suspect – resulted in angry demonstrations by Nepali labourers, outraged that one of their countrymen had been blamed unfairly for such a horrible crime. But the case has focused fresh attention on the uneasy relationship between India's middle classes and the ubiquitous servants who wash, cook, shop, drive, garden and clean for them. It has highlighted too, the deep anxiety of many Indians who live in perpetual fear that their servants will rob them, poison them or worse. A constant source of conversation among Indians who employ domestic staff, such fear has now even found its way into a popular new Indian novel that tells the story of a bitter and disenchanted chauffeur in Delhi who slits his employer's throat.

"We always get our staff verified by the police and we also try and get people who are recommended to us. Only then do we let them in our house," said Rosie Kapoor, a businesswoman from south Delhi, who employs one full-time and two part-time maids. "But even after all this I am still very careful."

While in the West servants largely belong to an earlier generation, in India they remain commonplace. Even families with a modest income will employ one or two maids; however industrious middle-class Indians may be in other respects, most have a loathing of domestic chores. In Delhi alone, it is estimated there are at least 60,000 domestic servants, of which perhaps just a third are registered with the police.

The maids, cleaners, drivers and cooks usually earn pitifully little and often live in miserable conditions. Often they are migrants from Nepal or else impoverished Indian states such as Orissa or Bihar. A full-time maid can earn as little as 2,000 rupees (£24) a month, supplemented with a meagre diet and perhaps some cheap clothes given to them by their employer. For this, the servant will usually work 12 to 14 hours a day, perhaps with one day off a week. Usually, servants will live in a simple one-roof shack or shed, often built on the roof of the house – swelteringly warm during the long, hot summers and bone-chilling in northern India's brief but cold winters. Most servants' bathroom facilities are probably best left undescribed.

And the relationship between domestic staff and the families they work for can have additional complications above and beyond the obvious financial disparity. Often staff will be from a lower caste than their employer, adding to possible mistrust and resentment.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that some employers treat their staff well, even almost considering them members of the family. On holidays such as Diwali and Holi, the staff will get a generous bonus or gift, they will receive their meals and clothes and time off to go back to their village or town if a family member is ill.

But there are numerous reports of employers treating their staff as little more than slaves. An 18-year-old who works as the live-in cook for a businessman in the Safdarjang area of south Delhi said that his every move was followed by CCTV monitors that his employer had installed in the house. The cook, Sushil, said that if he was caught leaving the house during working hours he was punished. He said that he, and two teenage girls employed as maids, were often beaten.

"If anyone makes a mistake, the boss beats them. He is dangerous," said Sushil, who came to Delhi from the Sultanpur district of Uttar Pradesh. "He hits the girls as well. He is a really bad man."

Sushil said that he earned 4,500 rupees a month but that he had to pay for his own food and clothes from this. In the three years he had worked at the house, his employer had never given him a holiday bonus.

Given the wretched, impoverished conditions in which India's domestic servants live it would perhaps not be surprising if servants were to turn to opportunistic crimes. "The class difference of employers and the employed is so big and that tempted them to commit crimes," a Delhi police spokesman, Rajan Bhagat, told the Associated Press.

But despite the widespread stories of chauffeurs routinely siphoning off petrol from their employers' cars, maids rustling through jewellery boxes when they should be sweeping the floor and newspaper cartoons showing Nepali servants chasing terrified elderly women, to what extent is the middle-class fear of their staff justified and how much of it is urban myth?

"I think it is real and I think we are hearing a lot less than actually takes place," said an expatriate living in Delhi who employs domestic staff and asked not to be named. "It's getting worse. [Domestic servants] can see the light. They know that money will give them a way out. It's something new. And people have to be careful."

While the media attention devoted to Aarushi's murder was exceptional, even the family's lawyer believes such servants are often responsible for crimes. Pinaki Mishra said there were many factors behind the phenomenon – increasing economic disparity, the increasing influx of rural people into India's cities and even mafia-style groups that force domestic servants to steal from their employers.

"India is an entire society in transformation," he said. "You have a middle class of up to 300 million people and below that you have an aspirational class of up to 300 million ... All the values are breaking down. No one wants to do menial work."

This view was shared by the family of an east Delhi businessman killed 10 days ago in his home. In this case too, the family's Nepali servant – employed for less than a year – has gone missing and police say he is a suspect. The businessman's hands had been tied behind his back and he had been strangled by a bed-sheet.

"Globalisation is the problem. Everybody wants a television, everybody wants the luxury. If they cannot get it by hook then they get it by crook," said the businessman's sister, her eyes red with tears. "We want to catch the person who did this to stop it happening again. We know we are not going to get our brother back but we are not going to lose our humanity."

Yet while such killings made big headlines, official figures suggest that the problem is not as great as some may believe. Mr Bhagat, the Delhi police spokesman, said that five people in the city with a population of more than 16 million had been robbed or killed by their servants so far this year. Last year the total was six.

Domestic servants say they are often blamed unfairly by their employers, the first in line to be accused if something goes missing. In the aftermath of Aarushi's death and the accusations that were made by police about the alleged guilt of the family's servant, dozens of other domestic workers gathered outside the local police station to complain. "We become prime suspects every time there is a crime in the house or the neighbourhood we work in," Ram Bahadur, a labourer, told journalists. "We are poor people trying to earn a living with dignity. Is it fair to suspect us without evidence?"

Sushil, the cook, said that he too was often accused of things, even though he insisted that thoughts of committing a crime had never entered his head. He said he was shocked by the murder of the businessman in east Delhi. "This is not something I think about," he said. "How can anyone do this sort of thing if he is a servant?"

The family of the murdered businessman said that they will no longer employ a live-in servant, even if it means they will have to perform the chores that their domestic help have traditionally carried out. "The culture can change. People can learn to adapt," said one of his sons, standing outside his father's store, talking with friends and relatives who had come to pay their respects. "They will have to change."

But are other Indians ready to give up their domestic staff and get down to scrubbing the dishes? Nishant Singh, a lawyer who works in Gurgaon, Delhi's Westernised satellite city, said the flurry of recent headlines would certainly encourage more people to think carefully about the staff they hire, about getting them verified by police and perhaps opting for part-time help rather than live-in servants.

But he doubted that Indians would forgo employing servants altogether. With the upper part of India's economy booming, more people had money to spend on help and with increasing numbers of women entering the workplace there was more demand for people to carry out the household tasks traditionally performed by women. "There has long been this concept of having staff," he said. "It's part of the culture."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments