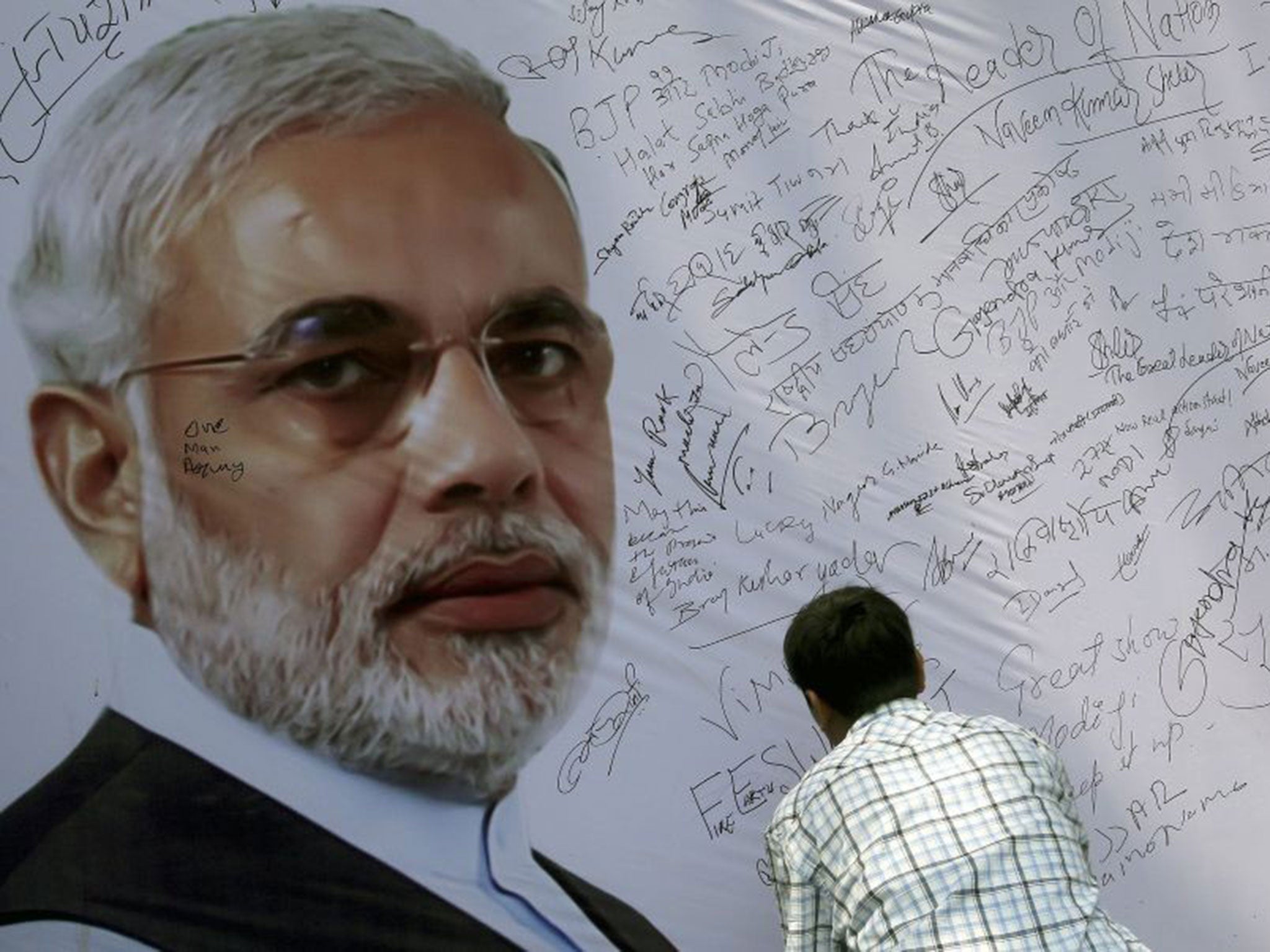

India election results 2014: How will Narendra Modi change the country?

The leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party looks set to become India's next prime minister. So what can he do for the country and where will it stand as a world power?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Economy

Modi campaigned on a platform of development and growth. He promised to offer a “red carpet” for investors and not more red tape. Large parts of the corporate world, both domestic and international, have supported his rise.

Economist Vivek Dehejia said there were several things Mr Modi could do quickly, such as change labour laws which businesses complain are overly restrictive. He could also offer a clearer taxation policy; large numbers of foreign companies were stunned by an attempt in 2012 by the Congress party to retroactively tax the British company Vodaphone for a 2007 deal.

Read more: Modi wave washes over India as Congress admits defeat

One controversial issue will be Foreign Direct Investment. The BJP has said it will welcome FDI in all areas which create jobs, but not in multi-brand retail, which includes supermarkets, because it does not want to upset the large numbers of small shopkeepers that make up much of its support.

Yet Mr Modi has indicated this could change. The retail business in India is expected to grow to $750-850bn by 2015 from the current $518bn. Organised retail accounts for just eight per cent of this.

The government has so far given permission to the UK retailer Tesco, the only applicant in the multi-brand retail sector, to purchase 50 per cent stake in Tata group’s Trent Hypermarket Ltd. India allowed 51 per cent foreign ownership in supermarket chains in September 2012.

“He will leave the multi-brand issue alone for a while. There is little profit for him in pushing it,” said Mr Dehejia, co-author of Indianomix: Making Sense of Modern India.

Cultural

There is a clear cultural element contained within Mr Modi’s Hindu nationalist party’s plans. Under the last BJP government, school text books were changed to reflect a certain view of history and that is likely to happen again.

The manifesto also promises to build a temple in dedication to Hindu deity Lord Ram at a disputed site in Uttar Pradesh, that was once the location of a mosque. The mosque was pulled down in 1992 leading to widespread clashes between Hindus and Muslims. The BJP has also vowed to introduce a “Uniform Civil Code” that would end the use of traditional laws by religious communities. It also plans to scrap so-called Article 370 of the Constitution, which gives special status to Kashmir.

The RSS, a Hindu nationalist organisation of which Mr Modi was once a member, is likely to have considerable influence on the BJP government. Siddharth Varadarajan, a journalist and broadcaster, said he expected Mr Modi would avoid making controversial comments or remarks on these issues himself. “He has other people in the food chain to do that,” he said.

Foreign policy

Most believe Mr Modi feels much easier looking eastwards, to Asian nations such as Japan, Singapore and Indonesia, than he does towards the West. It may be one of these countries that Mr Modi chooses for his first overseas visit as PM.

The US famously refused him a visa in 2005, something that still hugely rankled with both him and his supporters, and while the US has since sought to engage with Mr Modi the visa issue remains unclear.

Milan Vaishnav of the Carnegie Endowment in Washington believes that in economic terms, India and the US could help each other and that bringing in investment would support Mr Modi’s campaign vow. Yet he said that India’s strategic relationship with the US would be more problematic

He said he believed Mr Modi will attend the UN General Assembly in New York in September. “What I don’t think has been decided yet by the US is whether or not to invite him to DC for a meeting with Obama in the Oval office,” he said.

Relationship with Pakistan

Mr Modi and advisors have talked about getting tough with Pakistan and have criticised the way they claim Manmohan Singh failed to respond to repeated border provocations and the killing of Indian troops.

But another theory is that Mr Modi, as a conservative, may have more chance of brokering a breakthrough with his counterpart in Pakistan, Nawaz Sharif. Analysts point out that in 1999, it was the BJP leader Atal Behari Vajpayee, who reached out to Pakistan – then also led by Mr Sharif – by taking a bus to Lahore and trying to strike a deal.

“If a deal is to be done, there has to be a BJP government this side and a right-wing government that side,” said Vikram Sood, an analyst and former senior official with India’s foreign intelligence agency, the Research and Analysis Wing

Britain and India

In the aftermath of the 2002 killings of Muslims in Gujarat, Britain and much of the west enacted a de facto boycott of Mr Modi. That ended in October 2012 when the UK saw Mr Modi’s rise. There had been widespread lobbying from Britain’s Gujarati population to end it. British diplomats say UK businesses could benefit from a quicker decision-making process and less red tape that Mr Modi has promised to introduce.

“Britain is desperate for increased access to India’s markets, demonstrated by the visits of David Cameron to India. Britain needs India more than India needs Britain in this regard,” said Professor Katharine Adeney of the University of Nottingham. “While there are many who question Modi’s human rights record, and fear for the minorities in India under his watch, pragmatism will prevail over principle.”

Communal relations

Mr Modi has never escaped the accusations levelled at him over the 2002 killings in Gujarat but his supporters point out there have been no communal clashes there since. During the campaign he largely stressed development and growth and said all communities would benefit form them. However, a number of his senior colleagues made communal comments and were accused of fomenting tension.

Many Muslims clearly distrust Mr Modi, who has never apologised for what happened on his watch or made any effort to engage the Muslims. In Gujarat today, Hindu and Muslim communities are largely polarised – politically, geographically and socially. The BJP selected barely any Muslims candidates for the campaign.

Yet while some Muslims will remain anxious, most observers believe Mr Modi will work to ensure there are no clashes. “It would be counterproductive to Modi to let it happen,” said journalist and writer Hartosh Bal Singh.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments