Independent Appeal: The people for whom identity cards are a precious gift

A scheme which gives the homeless an address and a bank account is transforming the lives of some of India's dispossessed. Andrew Buncombe reports from Delhi

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

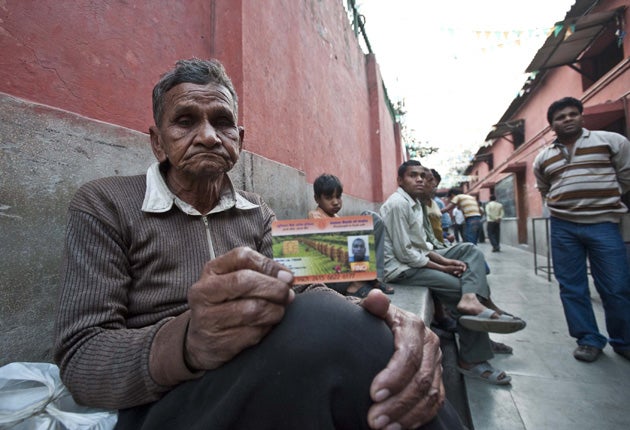

Your support makes all the difference.Amid a grey, throat-catching amalgam of dusk and dust in Delhi's Old City, an elderly man named Bhaia Lal Tiwari produced with a flourish a small plastic card that bore his name and photograph.

It didn't look like much, but to the old gentleman who retrieved it from his pocket with unobscured pride, it meant everything: after years of anonymity it had given him back his identity. "This card gives you such a lot of strength," said Mr Tiwari, the creases on his face breaking into a grin. "When I am outside and a policeman or someone else asks me who I am, it gives a different impression. It's a great support – it protects me."

The 66-year-old is at the very bottom of the pile. About 20 years ago a falling out with his family resulted in him moving to Delhi from the central state of Madhya Pradesh. For a long time he lived rough, sleeping on the side of the road or on a scrap of space at a railway station. He was regularly beaten by the police and his meagre belongings stolen by others who also had nowhere else to go.

But six years ago, Mr Tiwari moved into a shelter on the edge of the frenzied maze of the Old City. Here, every evening, tired lines of several hundred labourers and rickshaw-pullers queue up for a mattress and blanket and for just six rupees take their place on the floor of the shelter's pungent-smelling but spotless dormitory. When they leave the following morning, their places are taken by night-shift workers who tumble in exhaustedly and sleep during the day.

This simple shelter represents a daily lifeline for up to 400 of the city's most needy. But the charity that runs the establishment – ActionAid, one of the organisations being supported in this year's Independent Christmas Appeal – does more than just offer a place to sleep. It also provides its residents with an identification card that bears their photograph, their finger-print and lists the shelter as the individual's fixed address.

The true value of such a card is difficult to understand for anyone who has not had to fight just to stay alive. For many, if not most in India's seething, sprawling capital, every day is a battle for survival. In a city of at least 16 million people where the gap between the rich and the poor grows all the time, it is easy to fall through the cracks. It is a place, the Indian novelist Rana Dasgupta once remarked, "where one's social significance is assumed to be nil unless there are tangible signs to the contrary".

Those who struggle the hardest are those without documentation. In a society famous for its numbing bureaucracy, studies have shown that millions of poor people lose out on government services because they have inadequate identification papers. One of the country's leading entrepreneurs, Nandan Nilekani, was this summer appointed to head a project that will provide ID cards for a population of more than a billion people. It is not expected to be completed for at least three years.

"Providing ID cards is important because without an ID you cannot get anything," said ActionAid's Sanjay Kumar. "If you need something from the government you have to be somewhere on one of its lists. The homeless have never belonged anywhere. They do not exist and if they don't exist the government cannot do anything for them."

The charity estimates that in Delhi there are at least 170,000 homeless people who sleep on pavements, in temples or on pieces of waste ground. During the chill months of December and January, many die. And as India's rural migration continues, as more and more people move into the cities desperately hoping to receive a share of India's famed economic growth, the numbers of those with nowhere to live will soar.

"This is the dark side of the Indian economic growth story," added Mr Kumar, whose organisation Ashray Adhikar Abhiyan, or Shelter Rights Campaign, which is totally funded by ActionAid, operates 40 shelters in the city. "The Commonwealth Games is coming to Delhi and yet there are so many poor people here."

Another crucial service that has been organised by ActionAid involves using the ID cards to allow the residents of the shelter to open bank accounts. All banks demand that someone have an address to become a customer, but after negotiations with the charity, the Union Bank of India, a state-run institution, agreed to allow the shelter's residents to use the charity-issued ID cards as documentation. Around 500 such accounts have already been opened.

Now, several evenings a week, an official dispatched by the bank visits the shelter with a finger-print scanner and – having checked a person's print – collects small sums of money that are deposited into an individual's account. The residents of the shelter are also able to make withdrawals.

For those who have opened such accounts, the change has been nothing less than revolutionary. Now these people who live such harried, hard-edged lives and who have just the floor of a shelter to call home can at least stop worrying about where to hide their greasy, hard-earned rupees when they fall asleep. The ID cards and the bank accounts have also provided these people with something equally vital – a sense of respect.

Abdul Hussain is one of those who have recently opened an account. The 40-year-old has one of the hardest, most medieval jobs to be found in this often back-breaking city. At 6am every morning he starts work as a cart-pusher, shifting goods and materials at a nearby market. For this, if he is lucky, he will earn 200 rupees (£3) a day.

"This is the first time I have had a bank account," said Mr Hussain, who moved to Delhi from the southern city of Hyderabad 18 years ago. "This card has given us a lot of support. Before I deposited my money with a small money lender but this helps save our money. There is a sense of safety. Before coming to the shelter we did not have any support."

Mr Tiwari, who earns 2,000 rupees a month working in an electrical repair shop, also has a bank account as a result of his much-treasured ID card. "I was born in India and I have the right to live like a normal citizen. Before I was always fighting the system," he added. "Now I have a sense of support. If I did not have this card I would not have anything. I would not have an identity."

The charities: Who they are, what they do

ActionAid works in more than 40 countries, and is dedicated to ending poverty and injustice. It specialises in community development. Its projects include one aiming to help poor women in Ethiopia to buy their own shopping mall, working with farmers to fight climate change in eastern Africa's Rift Valley, helping sex workers in the world's biggest brothel in Bangladesh, and supporting a school in Afghanistan for child soldiers rescued from the Taliban.

ComputerAid International collects old computers in the UK and refurbishes them to send out free to schools and charities in the developing world. Its 150,000 computers are helping African meteorological offices to advise farmers, and allowing rural health workers to send X-rays over the internet for diagnosis from specialists.

Peace Direct sets up initiatives among local people to lessen tension in conflict zones, mindful that many conflicts fester and often reignite after peace deals. Peace Direct brings Muslims, Sinhala Buddhists and Tamils together in Sri Lanka. It funds Afghanistan peace councils. It eases tensions in Northern Ireland. And it works on relations between oil companies and locals in Sudan.

The charities all have extraordinary stories to tell. We hope you will give generously.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments