'I was desperate, hopeless, but I wasn't going to give up' says K2 survivor

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Marco Confortola had a bad feeling from the moment he first approached K2. "The soul of the mountain was not going to let us succeed," he says with a sigh, his eyes closed at the painful memories. "A toll was going to be paid."

The Italian climber could scarcely have imagined how great that toll would be. In the course of three days, 11 mountaineers perished on the Pakistani peak, Everest's slightly smaller but deadlier brother which has the reputation of being much harder to climb. It was the worst K2 tragedy in more than two decades.

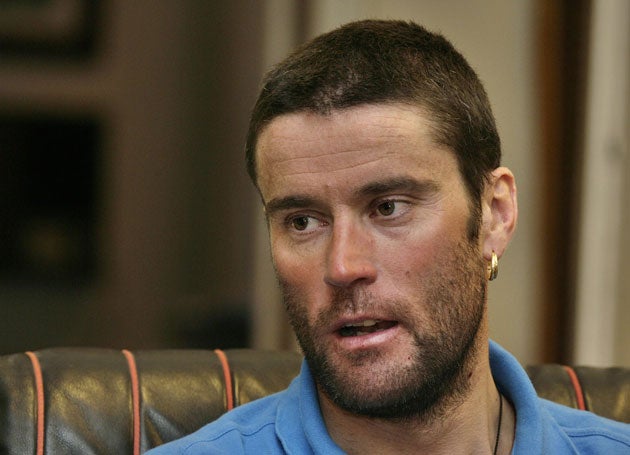

Sitting in a wheelchair, his legs too weak to support him and his black frostbitten toes bundled up in bandages, Mr Confortola cannot hide his relief at having survived the ordeal, cheating death at least three times and braving four nights of freezing temperatures and exhaustion with scant oxygen and no food. "My feet are killing me, but otherwise I feel OK," he says in his first newspaper interview since being rescued. "I am now on the safe side – out of danger."

His friends say it is the mental trauma he has suffered that most worries them . Confortola, 37, has spent the past few days in Islamabad in a deeply emotional state, venting anger at what happened and occasionally being reduced to tears. And during the interview the grief for his dead companions – particularly the Irishman Gerard McDonnell – threatens to consume him.

It was with McDonnell that the Italian had scaled the peak, reaching the summit at 7pm, just as darkness fell. The pair embraced, but had little time to enjoy their triumph. They had already seen a Serbian climber plunge to his death and were worried about being stranded. But after a short descent, they decided it was too dangerous to continue in the dark and stopped for the night.

Confortola dug two small pits with a stick to make a makeshift shelter for the night. "Since Gerard was having a difficult time, I made his hole bigger to help him lie down for a little bit. Gerard was very cold. I was also cold and began to shiver on purpose to create heat. I was wasting energy, but I needed to get warm." They were perched on the edge of a sharp slope. "I made sure not to fall asleep, because I could have fallen over," he says.

In the morning, they set out again and after a short while, they came across three climbers from South Korea, hanging upside down, held by a cord attached to their waists. Two were unconscious. For three hours, McDonnell and Confortola tried to right them, but it was in vain. All three died. It was at that moment, "for some strange reason", that McDonnell began to walk away. It was the last time Confortola would see his friend alive. Exhausted, he fell asleep, only to be woken by an ominous rumbling. "All of a sudden I saw an avalanche coming down. It was only 20 metres to my right. I saw the body of Gerard sweep past me," he says, covering his eyes once again.

The mere mention of McDonnell and Confortola's voice turns shaky, his eyes welling up. "When you are up in the mountains, it's easy to become friends, but it was particular with Gerard," he says. "I used to call him Jesus," he adds, gesturing above. "The beard, everything, he looked like Christ. He was always smiling. He was a flower."

The Italian climber shrugged off suggestions that the six teams – from Ireland, South Korea, the Netherland, Serbia and Italy – had displayed poor judgement, insufficient preparation and had caught so-called "summit fever". "We were well prepared," he says. "We had made our plans – even the weather was good."

But later Confortola described how after the first fatality at the so-called Bottleneck – a rocky and narrow passage less than 1,000 feet from the summit – he was the one who pushed them to press on. "Nobody was willing to go up first," he says. "We didn't have the right ropes for that part of the climb. But I started shouting. I told them that the first person to reach the summit of K2 did it at 6pm, so let's move!"

It was at the Bottleneck that calamity struck on the descent. An ice pillar broke off, snapping the ropes and causing an avalanche. Confortola recalls how McDonnell's body had been torn to shreds by the impact of the avalanche and all he could see were the separated parts tumbling down the mountainside. "Yes, it was very bad," he says quietly.

Shortly afterwards, one of the Nepalese porters appeared and offered oxygen – which he gratefully accepted. "The Sherpa took me to meet Wilco and Cass," he says, referring to the two Dutch climbers rescued a day before him. "When we were walking down another avalanche struck. It hit two Sherpas who were helping us. And an oxygen bottle came cascading down and hit me in the back of the head." Confortola bends forward to reveal a round black mark near the base of his skull.

It was at this point that Confortola was certain he would die. "I was falling," he says, gesturing animatedly. "The avalanche would have taken me away with it. But I was lucky. One of the Sherpas, his name was Pemba, grabbed me from behind. He was holding my neck. He saved my life."

Pemba helped him stagger down. The military helicopter dispatched to rescue him could only fly so high, and he had to persevere for another night before being picked up and taken to a hospital on Monday. "I was desperate, almost hopeless," he says. "But I was not going to give up. I was going to make my way down even if it meant having to walk all the way to Islamabad."

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments