How I survived Cambodia's Killing Fields: Acclaimed surgeon SreyRam Kuy celebrates her mother's determination to escape to the US

Born in Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge, SreyRam Kuy's mother fought like a tiger to survive the Killing Fields - and life in a strange new land

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It was 1978, in Talien, Cambodia, when the Khmer Rouge soldier came for my mother. An acquaintance had betrayed her, informing the Khmer Rouge leadership about her past as a teacher. Under Pol Pot's savage regime, all educated citizens – teachers, doctors, musicians, artists and intellectuals – were to be interrogated, tortured and killed, and until her name was given up, she had been able to hide her profession during questioning.

My grandmother sobbed, pleading to take her daughter's place. But the soldier didn't want an illiterate old woman. Pol Pot's orders were to eliminate the educated.

At the communist headquarters, kneeling before the Mit, the local Khmer Rouge leader, who was flanked by grim-faced soldiers, my mother didn't beg for her life. Instead she asked if she could tell a story. Puzzled, the Mit nodded. Used to entertaining her students with vivid fairytales, my mother began to tell a story about a wealthy merchant and his faithful guard dog. She described how a thief tricked some villagers into believing the merchant's dog was rabid and enlisted their help in clubbing the innocent dog to death. After the murder of the guard dog, the scoundrel returned at night to rob and kill the merchant.

"I am like that dog," she said. "I'm just a simple, loyal, dumb beast. I am no teacher. I can't read. I can't even write my own name. If you believe them and kill me, you will be tricked, just like those foolish villagers."

Caught up in her storytelling, the Khmer Rouge ended up releasing her. She walked back to her family, convinced she had witnessed a miracle – no one who was taken away by Pol Pot's men returned alive. It was one of many times my mother escaped death during the four years of the Killing Fields, and one of many times she used her mind and wits to help herself and her children survive.

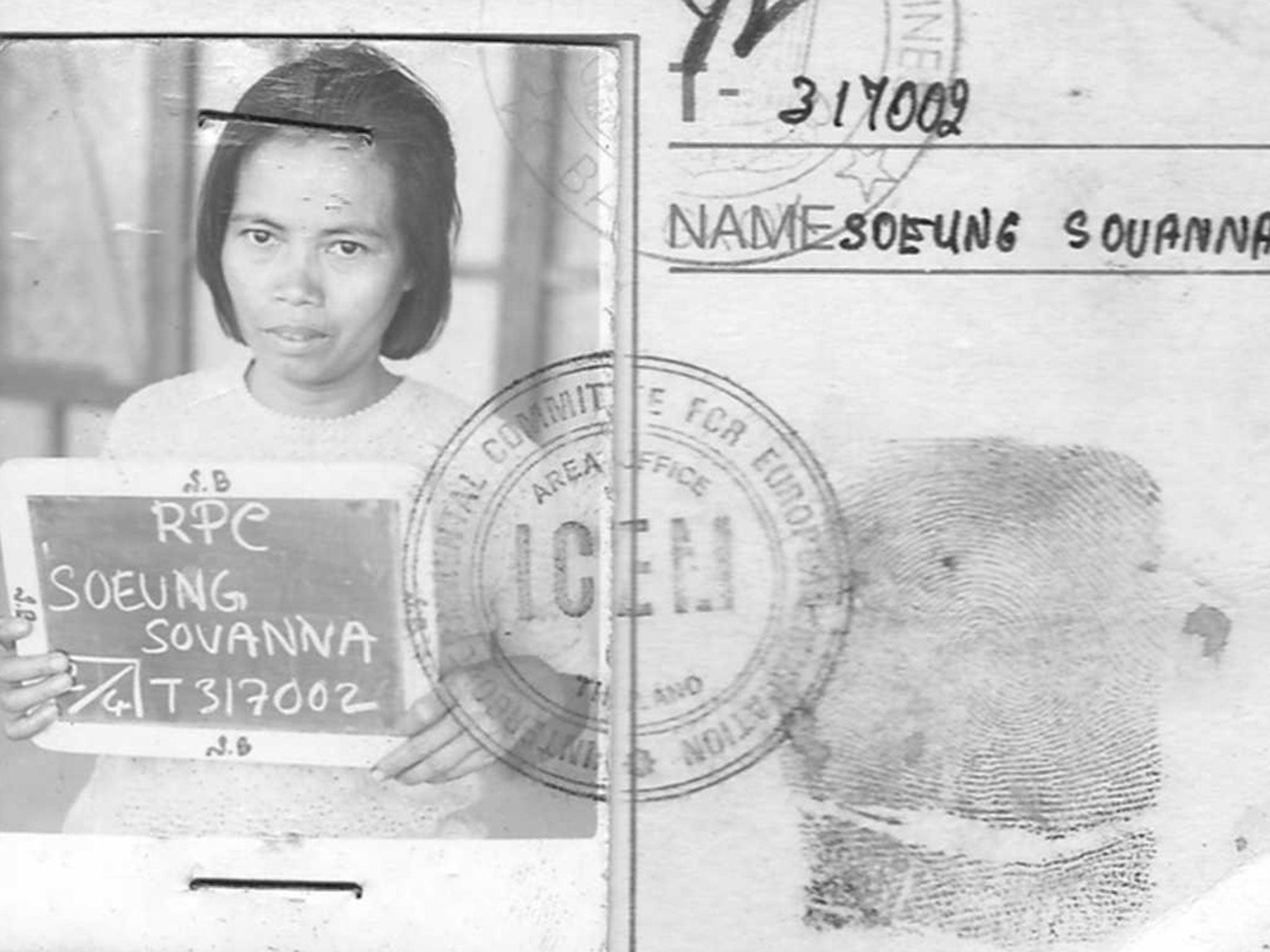

For my mother, Sovanna Soeung, education was the key to escaping the poverty of her childhood and, eventually, genocide. Growing up in 1950s Cambodia, my mother, small, scraggly and stubborn, dreamed of going to school and becoming a teacher, one of the most respected professions in Cambodia. None of her four older sisters were allowed to attend school beyond junior school; at age nine, my mother had never entered a school building or opened a book. Societal norms – and her father – dictated that women should not be educated.

But my grandmother, a sweet-tempered woman who generally obeyed her husband, disagreed. She marched her youngest daughter to the school house, several miles from their rural farm, and enrolled her.

At that time in Cambodia, education was a luxury for the sons of well-to-do families. My grandma chopped wood in the forest and rolled incense sticks to sell at the market. My mother picked wild herbs and caught fish in the nearby stream to sell. Together, they scraped together the meagre riels (Cambodian currency) needed to pay for school. In a threadbare school uniform, tattered books in hand, my mother excelled and eventually became a teacher.

My mother enjoyed a few carefree years as a young teacher. She married, had a baby girl and moved to the capital city of Phnom Penh with my grandmother. But by the early 1970s, there were rumblings of warfare. Soldiers began patrolling the streets, and refugees from the countryside flooded the cities to escape bombings. Most Cambodians thought that the war would end and life would go on as usual, until April 1975, during the Cambodian new year. The atmosphere was ebullient, as children played games, young women performed the ancient Apsara dance and everyone feasted on banana leaf-wrapped tapioca treats and ahn som, sweetened sticky rice and savory pork. My family was startled by gunfire outside the house. Khmer Rouge soldiers in plaid karma scarves burst into homes, forcing families into the streets at gunpoint. Anyone who resisted was shot. That day, millions of Cambodians were driven from the cities and forced to begin a life of slave labour, and Pol Pot's savage quest to murder the country's educated citizens commenced.

About two million died during the Killing Fields, from torture, execution, starvation and disease. Some committed suicide to escape the nightmare, but my mother persisted. She sneaked into the jungle at night after working all day in the rice fields to forage for food for her family. She dug up bamboo shoots from a creek bed with her bare hands. She once stumbled upon a litter of tiger cubs and didn't stop running until she made it back to our shack, breathless and terrified. But she still needed to feed us, and she returned to the river bed to gather more bamboo shoots. She had the heart of a tiger.

Four vicious, bloody years later, the Khmer Rouge was overthrown, and Cambodians were released to return home. We had nothing but the rags on our backs. Our home in Phnom Penh had been demolished and my mother's family farmland taken over by squatters.

My mother took my sister and me, now aged five and one, to glean a rice field after harvest. We ended the day without a full handful of rice. A man loading the rice wagon took pity and gave us several handfuls of rice. At home, we pounded off the chaff. My mother took the small portion of rice and made a watery porridge for the family. That was life in Cambodia after the war.

My mother realised then that there was no hope for her daughters in Cambodia – no universities, hospitals or opportunities. Education had been her ticket to escape poverty, and she believed it was the only way for a better life for her children. She decided to leave.

Since the overthrow of the Khmer Rouge in 1979, 750,000 Cambodians tried to flee the country. Thousands died attempting to cross the landmines that lined the borders. In May 1980, we began our escape. We fled through jungles laced with landmines and crawled under a rusty, barbed wire fence to get to the Khao-I-Dang refugee camp, across the border from Cambodia. We thought we were safe.

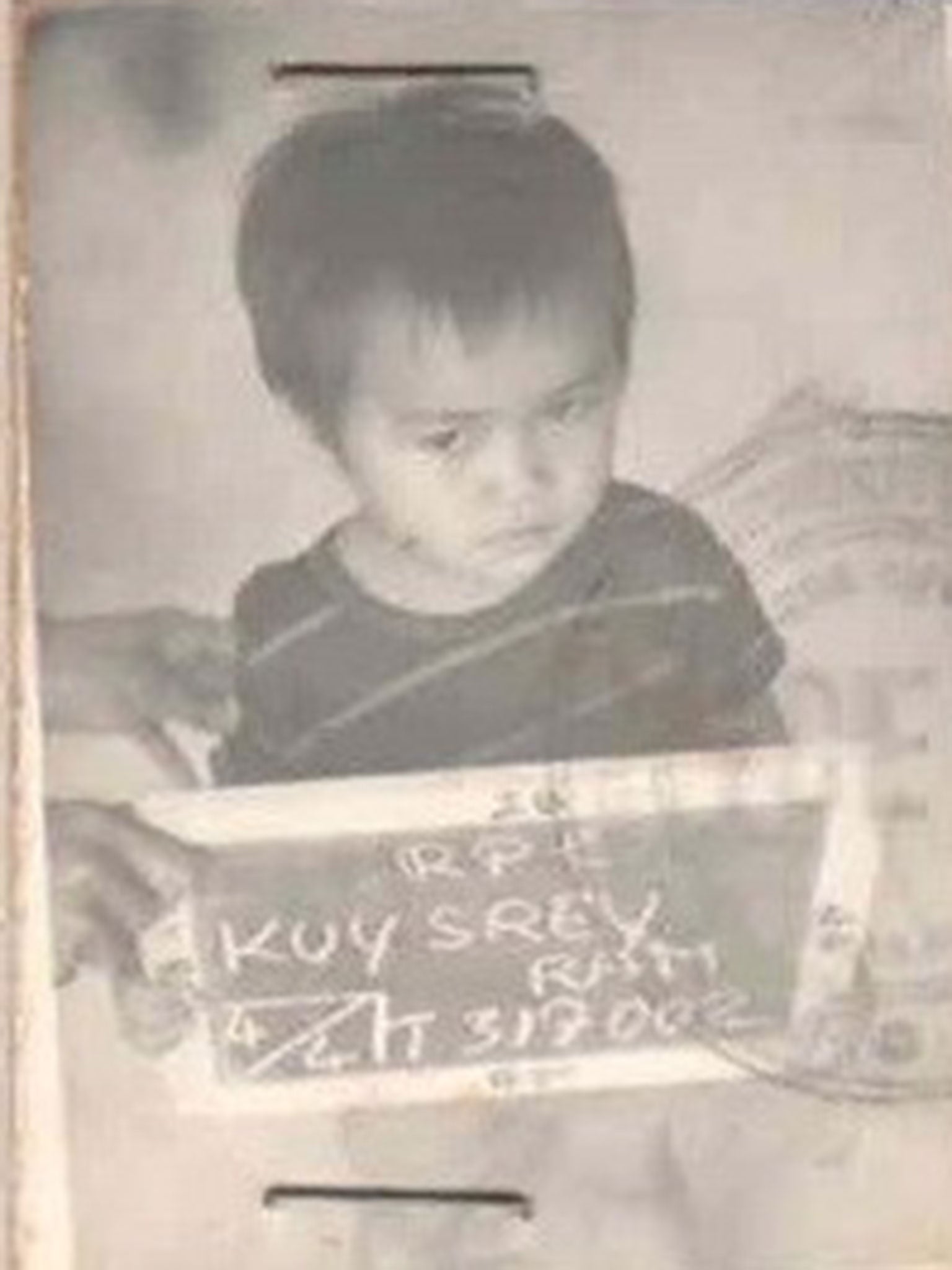

Two weeks later, errant border patrol shells hit the camp. One shell detonated near our tent. Shielding her children with her body, my mother sustained most of the impact of the explosive and was severely wounded. My left ear was partially torn off. My sister was covered in lacerations. A German Red Cross surgeon operated on me, stopping the bleeding from my scalp and sewing my ear back into place, and on my mother. Today a scar runs by my left ear and down my jaw; disfiguring cicatrices lacerate my mother's belly and gnarl her arms – reminders of the debt we owe that surgeon.

We lived in four different refugee camps for a year and a half before we recieved the news: We had been sponsored to the United States by a Christian missionary group.

My mother arrived in the US destitute, unable to speak the language and ravaged by memories of the Killing Fields. With two children in tow, she clung to her faith and hope for a new life. She scrubbed toilets at the Good Samaritan Hospital in Oregon during the day and cleaned houses for doctors in the evening. Late at night, she mopped floors at the Oregon State University thrift shop. Still weak from the injuries she sustained during the bombing, she would walk one block, then stop and sit to rest before getting up to continue her walk to work. In the summer, we worked in the fields of Oregon's Willamette Valley alongside Mexican migrant farm workers, picking berries, tomatoes and garlic.

My mother, who had worked so diligently to get an education, was never ashamed of her work. She was proud to be an American and to work so that her children could go to school. She instilled in her daughters courage, gratitude and faith in a miraculous God.

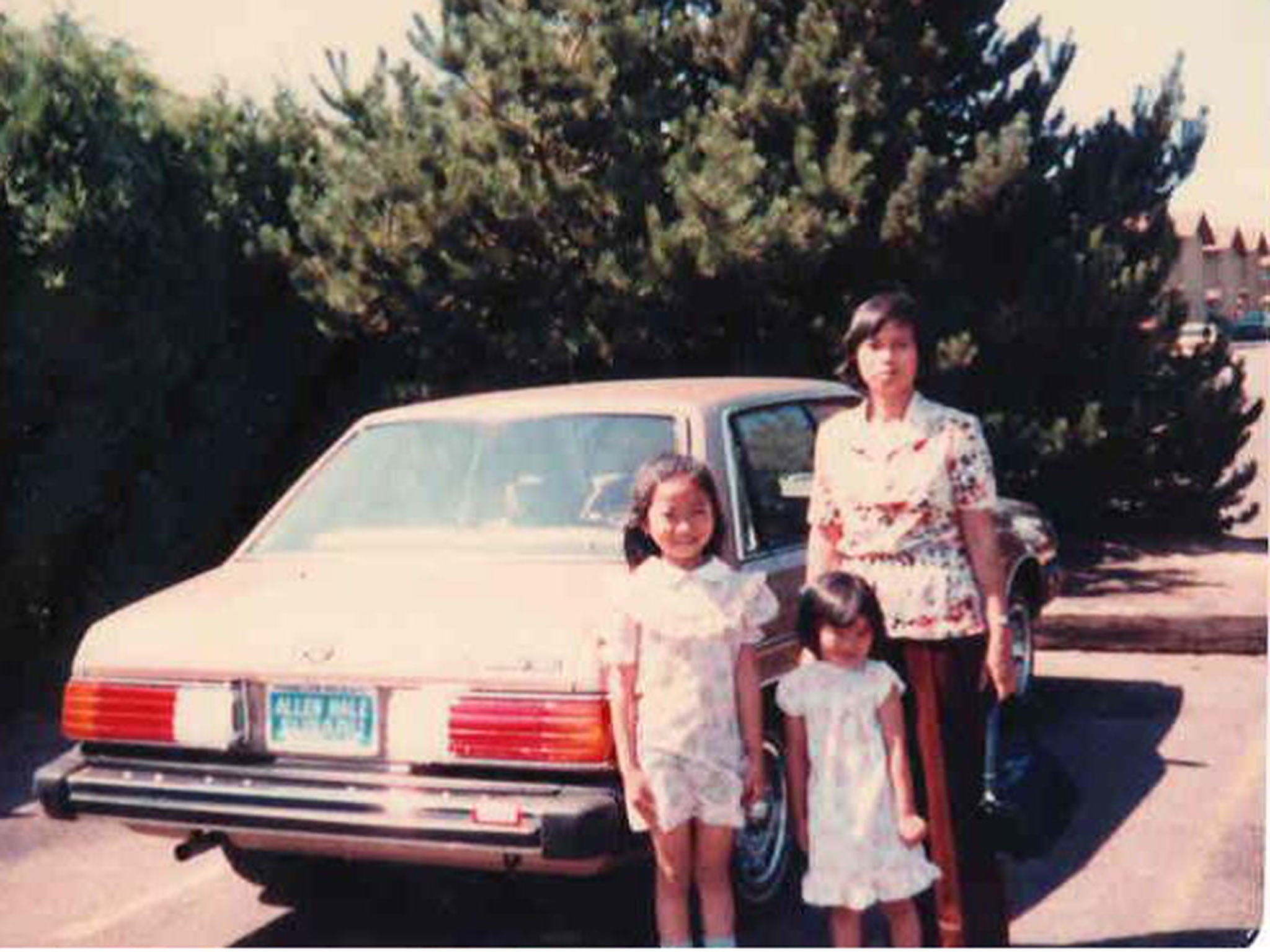

After more than a year of scrubbing toilets, mowing lawns, cleaning houses and picking berries, we finally saved up enough money to buy a car. My mother showed up to the first car dealership, wearing shabby clothes from the reject bin at the charity shop we cleaned at night. "We buy car," she excitedly said in her broken English, pulling out stacks of one, five, 10 and 20 dollar bills. The first dealership turned her away, unsure of what to make of this bedraggled bag lady. Undeterred, we went to another dealership which sold us a Nissan Sentra.

Thanks to this work ethic ingrained in me by my mother, I graduated from Crescent Valley High School as the valedictorian (graduating with the highest grades) and attended Oregon State University – the very school where my mother mopped floors. I went on to earn a medical degree at Oregon Health Sciences University and a Master's in health services research at Yale. Today, 35 years after leaving Cambodia, I'm a surgeon. My mother cleaned bedpans at Good Samaritan Hospital; now I operate on patients at Overton Brooks VA Medical Centre. My mother fought to read in a one-room, rural school house. I learned from dignitaries and power brokers in the Ivy League. My sister is a podiatrist, taking care of patients with renal failure and diabetes.

Now in her early 70s, my mother still has the same untameable spirit. In January, she returned to her home village in Cambodia for her third trip. She led worship services, helped to baptise 33 people, passed out nearly 1,000 Khmer language Bibles and distributed new school uniforms for children.

My mother doesn't like to say that she's proud of us. Mostly she says that she's happy for us – happy that her children had a chance at an education. The very fact that I survived, when so many lost their lives during the Killing Fields, is astonishing and humbling. That my sister and I work as doctors, safe and free, is a miracle.

SreyRam Kuy, MD, is the author of the forthcoming book 'The Heart of a Tiger'

© Washington Post

Legacy of the Khmer rouge

By Andrew Buncombe

In the four decades since the Khmer Rouge took power, Cambodia has not been a happy country. But how could it be, when a former Khmer Rouge commander still rules?

In 1998, when Hun Sen manoeuvred himself into the premiership, he was one of the world's younger leaders. Now 62, he is one of the longest-serving – and shows no intention of stepping aside.

His story is remarkable in so many ways. In 1975, he was among the Khmer Rouge rebels who swept into Phnom Penh and set the country on a deadly, regressive course of agrarian socialism. Anywhere up to a fifth of the population – an estimated 1.7 million, lost their lives either through hunger, exhaustion or in the countless "Killing Fields".

In 1977, during a purge, Hun Sen fled to neighbouring Vietnam, only to return to Cambodia two years later when Vietnamese forces invaded and he found himself a major figure in the new regime imposed by Hanoi. While the Vietnamese departed in 1987, Hun Sen never left the centre field of politics.

Most in Cambodia, where more than half the population is estimated to be under 25, have never known a time when he was not a central figure. And his grip on power has tightened, not lessened, during the years when the country has described itself as a democracy. Potential rivals within his own party have been given senior positions, alongside members of his family, while opponents such as Sam Rainsy, have been smeared, sidelined and out-manoeuvred. His administration has been often accused of torturing, and even killing, dissidents.

Hun Sen's cementing of political power has taken place alongside painful efforts to try and bring to justice some of the premier's former senior colleagues. The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia was finally established in 2006, to try some of the ageing senior Khmer Rouge figures.

In 2010, Kaing Guek Eav – also known as Comrade Duch, who oversaw the Tuol Sleng interrogation camp in Phnom Penh – was found guilty of genocide and crimes against humanity, and a court sentenced him to 35 years imprisonment. Last summer, Khieu Samphan, the 83-year-old former head of state of the Khmer Rouge, and 88-year-old Nuon Chea, its chief ideologue, were similarly found guilty.

But they are slim pickings. Five KR leaders had originally been brought for trial. But the former foreign minister, Ieng Sary, died in 2013, while his wife, the social affairs minister Ieng Thirith, was deemed unfit to stand trial. The most senior leader, Pol Pot, died in 1998.

Whether there will be any more trials remains unclear. The tribunal has been rocked by allegations that Hun Sen was trying to interfere. He has said that he believes it threatens to tear society apart. However, commentators have suggested privately that he simply wants to protect colleagues. Forty years after the Khmer Rouge seized Cambodia, the impact of their actions continues to reverberate.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments