How Hong Kong avoided a single coronavirus death in care homes

Care homes learnt a ‘painful lesson’ from SARS, and quickly sprung into action to make sure the same thing didn’t happen with Covid-19, as Laurel Chor reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

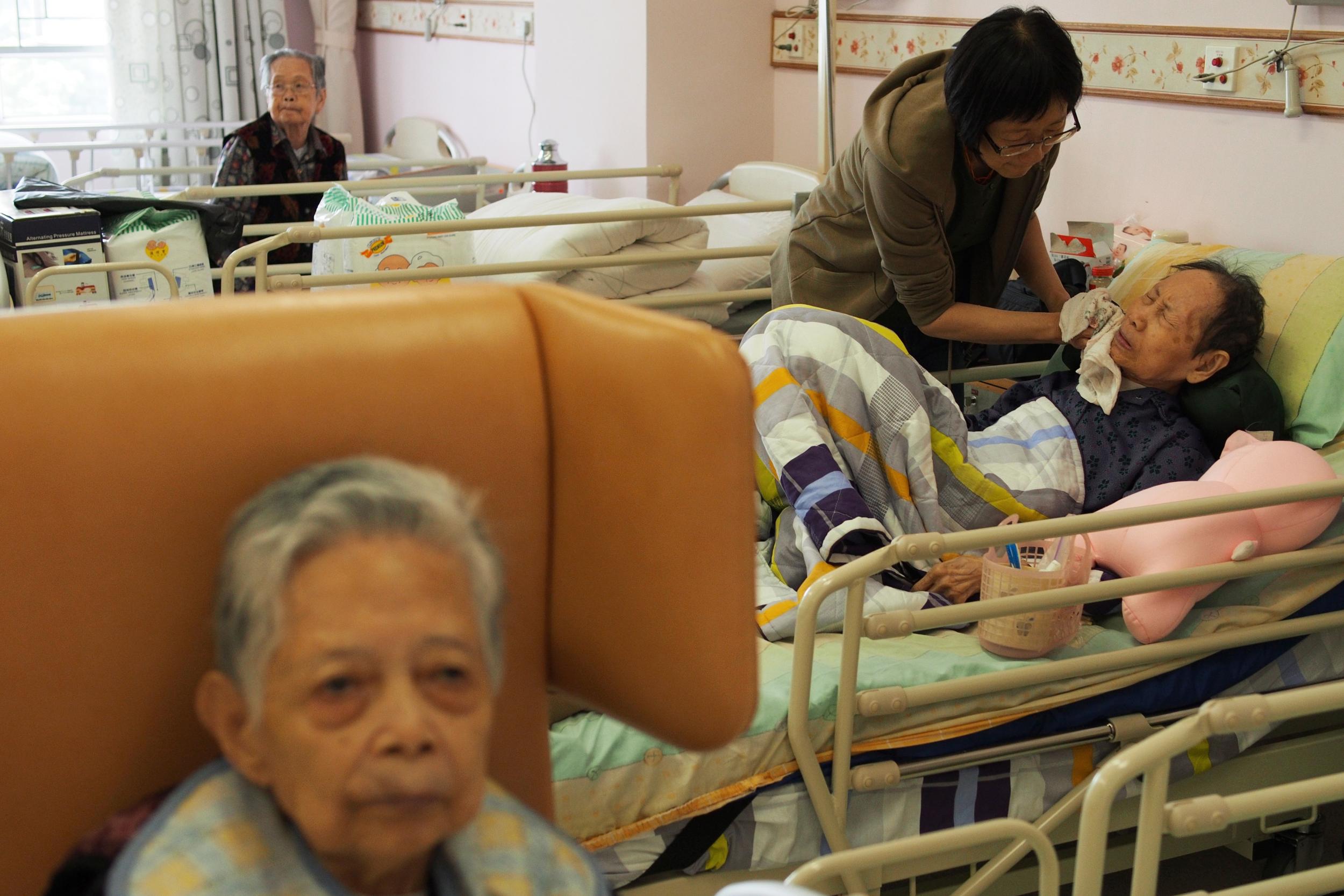

Your support makes all the difference.Coronavirus has ravaged care homes across Europe and America, killing tens of thousands, but in Hong Kong, not a single resident in care has even contracted Covid-19. Its apparent success offers vital lessons – ones that the city learned the hard way almost two decades ago.

In Sweden and Belgium, care home residents make up roughly half of each country’s Covid-19 deaths. In Spain alone, almost 18,000 nursing home residents have died from the virus, El País estimates. And in England and Wales, more than 90 per cent of those who have died from the coronavirus have been people over the age of 65, including 12,500 care home residents, according to the Office for National Statistics.

No one would have been surprised if Hong Kong suffered from a major Covid-19 epidemic. It shares a border with mainland China, which is crossed by hundreds of thousands of people every day. Most of the city’s tourists come from the mainland, accounting for tens of millions of visitors every year. In early February, Hong Kong had its first death from coronavirus – only the second death outside of mainland China. But to this day, there have been only four Covid-19 deaths in Hong Kong, a city of 7.5 million.

This is not the first time Hong Kong has faced a novel coronavirus. In 2003, six years after the former British colony was handed back to China, it became the epicentre of the SARS outbreak: 299 people died, accounting for almost 40 per cent of the global death toll. The disease had first appeared the year before in Guangdong, the Chinese province that borders Hong Kong.

As is the case with Covid-19, the elderly were the most susceptible to SARS, and similar to the UK, about a fifth of Hong Kong’s population is over the age of 65. By the epidemic’s end, 54 nursing homes had had cases of SARS. Two nursing home workers died. It was not a trauma the industry would quickly forget.

“The nightmare of SARS is still on everyone’s minds, so [care homes] were really afraid,” Prof Terry Lum, the head of the department of social work and social administration at the University of Hong Kong, told The Independent.

“We had learned a very painful lesson,” he continued, “and since then the nursing homes had been preparing for another outbreak.” Seventeen years after SARS, Hong Kong’s nursing homes were taking no chances.

On 21 January, an infected tourist from Wuhan crossed the border into Hong Kong, becoming the city’s first case. Four days later, the government announced that it would be enacting the emergency phase of its infectious disease protocol.

Because of Hong Kong’s collective memory of SARS, individuals, organisations and businesses did not need to wait for instructions from the government. Nursing homes enacted their own measures, Prof Lum recounted.

They began limiting the length of workers’ leaves, in order to prevent them from taking weekend trips to mainland China and possibly bringing the virus back. When nursing homes were instructed to take the temperature of all visitors, they took it one step further: they banned visitors altogether, effectively closing off their residents from the outside world by the end of January. There were still only 13 confirmed cases in Hong Kong at the time.

To stop the spread from hospitals into nursing homes, any confirmed cases were also quarantined for up to three months. Testing is available free of charge to all patients who exhibit symptoms, whether at private or public clinics, with the government continuously expanding its capacity to test asymptomatic people.

The Facebook page for care home China Coast Community once served as a chronicle of the lively visits, parties and performances that brought joy to its residents year-round. But since the beginning of 2020, the tone of the posts took a turn as the community locked down; one post showed a sign that said “NO VISITORS!!!” in a bold, red font, highlighted in yellow.

The lack of visitors has taken its toll. “We are missing our visits from family, friends, and volunteers,” said one post in February. One of the nurses had begun cutting the residents’ hair. A post in late March lamented: “We have lost track of how many weeks our restrictions have been in place.”

But still, the home was proud it upheld its rules: “It’s reassuring to know the rigid restrictions we put in place all those weeks ago, has reduced the risk and spread of infection amongst our Residents.”

Protecting the elderly from the virus is protecting the healthcare system, which protects everyone

Social activities were cut down, as well: mahjong – a tile-based game that’s a favorite pastime among Hong Kong’s older generations – was no longer allowed. Recently, some care homes allowed their residents to play again, much to their delight.

“It was really difficult for them [to stop], so they’re very happy now,” said Henry Shie, the chairman of the Association of Bought Place Elderly Services, which manages around 1,300 beds in care homes. Tables are now further apart, and the elderly, usually reluctant to wear masks, are more than happy to do so in order to play. “Ok, I’ll put on a mask, just let me play mahjong!” Shie recalled them saying.

Technology has also helped to lessen the loneliness brought on by fewer visits and social activities. “Through WhatsApp video calls, they can see their family members,” said Alex Au, who’s in charge of the Tung Chung Silverjoy care home. His staff try to arrange calls for each resident every week to “maintain the elderly’s connections with their families”, often to emotional effect. “Sometimes, the elderly resident cries, the family also cries, they cry with happiness.”

Wherever possible, nursing home residents were no longer taken to hospital for medical visits. This was relatively easy to accomplish: after SARS, the Hong Kong authorities ramped up the capacity of its visiting doctor programme for care homes.

Doctors understood that the fewer hospital visits the elderly make, the lower the risk of transmitting disease. “Treating sick elders within the old age homes, as far as possible, is an effective way to halt infections spreading to and from these elders,” Dr Sammy Tsoi wrote, back in 2004, in the journal of the Hong Kong College of Family Physicians.

Masks and other protective equipment were also an essential part of the care homes’ defensive strategy. Though the rest of the world would continue to debate the efficacy of masks for months during the Covid-19 pandemic, Hong Kong experts have advocated their use for years, with Hong Kong people – battle-tested by SARS – following suit, with none of the resistance seen elsewhere.

“Hong Kong and all other locales that adopted universal masking early in their outbreaks dramatically suppressed or drove down daily case growth rates, even though some of those locales did not have other strong interventions such as contact tracing or testing,” said Prof De Kai, a leading machine learning scientist based in Hong Kong.

Surveys found that 7 out of 10 Hong Kong residents were already wearing face masks in January. They continued to do so despite the city’s leader, chief executive Carrie Lam, instructing her own officials to stop wearing masks, to the criticism of local experts. By the beginning of April, almost everyone – 96.6 per cent of residents – was wearing face masks, according to another study.

The lessons learned from SARS proved to be lifesaving, time and time again. Although the city’s mask supplies quickly began running low, Prof Lum said most nursing homes kept one to three months’ supply of protective equipment. Along with the thousands of masks donated to them by various community charities, their stocks bought them time before the government began distributing 2 million masks to care homes a month from April onwards.

Perhaps most importantly, Hong Kong’s health workers understood that it was critical to prevent Covid-19 from spreading among the elderly not only because they were the most vulnerable, but because it would save the healthcare system from eventually becoming overwhelmed. Elderly people are more likely to contract the virus, more likely to be admitted, more likely to stay longer, and more likely to need ventilators – taking up precious resources.

“So far we have zero infections of frontline healthcare workers. It’s a totally different story in the UK, in Italy, or in the US,” said Prof Lum. If there’s one takeaway he wants the world to know, it’s this: “Protecting the elderly from the virus is protecting the healthcare system, which protects everyone.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments