Gandhi Jayanti: Mahatma Gandhi’s heart beats again as India begins celebrating his 150th birthday

Commemorations for landmark anniversary set to last two years as world reflects on what Gandhi's legacy means today

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Blood-stained and riddled with bullet holes, the robes Mahatma Gandhi wore when he died are the star attraction at the national museum dedicated to him in Delhi. Now, in the next room and 70 years after his death, visitors will be able to listen to the beating heart of the man known here as the “Father of the Nation”.

The installation, modelled on Gandhi’s real heart rate measured by ECG in 1937, is just one of a range of initiatives being launched on Tuesday to mark the national holiday of “Gandhi Jayanti” – Gandhi’s birthday.

This year the commemorations are particularly ambitious because 2019 will be the landmark 150th anniversary of Gandhi’s birth. The government has said that, starting on Tuesday, it wants to lead the world in two full years of celebrations honouring the independence leader’s legacy.

That legacy, though, is hotly contested. Across the country, children will mark the day by learning about Gandhi in school, dressing up in his trademark white dhoti and wire-rim glasses and emulating his teachings by performing community service – often cleaning.

The prime minister, Narendra Modi, is expected to give a speech marking the occasion and will order the early release of possibly thousands of convicts jailed on lesser charges, in what his government called a “homage to the humanitarian values Gandhi stood for”.

Outside of India, the rest of the world will observe 2 October as International Day of Non-Violence, remembering Gandhi’s single most important principle of resistance without bloodshed. But while all these tributes will be positive, experts argue it is a mistake to see Gandhi as someone who can be safely consigned to history.

“The problem with Gandhi is that he refuses to remain trapped in the past,” says Faisal Devji, professor of Indian history at Oxford University. “Whether it is for his acolytes or his enemies, he remains very much a living figure in India today.”

For Dr Devji, a “great example” of this is the shutting down of a copper smelting site in Tamil Nadu, southern India earlier this year, after 13 peaceful environmental protesters were killed by police gunfire during marches and sit-ins at the site.

Even without invoking Gandhi’s name explicitly, the protesters defeated the plant owners using methods that are immediately recognisable as Gandhian, Dr Devji says.

“Gandhi’s idea was that you have to demonstrate you are willing to absorb more violence and sacrifice more than the violent person,” he explains. “You literally have to invite violence and redirect it towards yourself, and it takes guts to do that.”

Gandhi’s legacy is strongest when it is inspiring activists and protesters, Dr Devji says, but his influence is so pervasive that he also gets cited on behalf of causes which he showed little interest in during his lifetime.

The ‘India Against Corruption’ movement (in 2011) explicitly used Gandhian leaders as a mobilising force, he says. “Gandhi of course would have been against corruption, but he never made that the foundation of any of his movements.

“It’s not that it didn’t exist at the time, but Gandhi realised it is not a political issue, it is a structural problem. Technically everybody is against corruption, you can’t draw a line and argue either side. So of course it is a problem, but it’s not one Gandhi himself really went into in his work.”

For Ramachandra Guha, an author and Gandhi biographer who has just published a 1,150-page book seen as the definitive history of Gandhi’s years in India, many of the claims staked on the great leader’s legacy are problematic.

That’s because most people who say they are honouring Gandhi are actually engaging in cherry-picking, he says. He reserves his fiercest criticism for those who celebrate Gandhi for winning India’s freedom while supporting oppressive policies against India’s modern-day minorities.

“Of course Gandhi wanted to rid this country of foreign domination, but he also urged Indians to look within at the failures and fault lines in their own society,” Mr Guha says.

“His campaign against untouchability was based on the premise that if we so grossly oppress a section of our own people, we are not fit to claim freedom from the foreigner. Likewise his campaign for Hindu-Muslim harmony was based on the premise that even if freedom came, he did not want Hindu domination.”

By taking foreign leaders to see Gandhi’s home in Ahmedabad, plastering the image of Gandhi’s glasses across government programmes and, most recently, dedicating a UN environmental champion award to Gandhi, Mr Modi is “associating his name” with that of the national hero, Mr Guha says.

“At the same time, if Gandhi’s central message was that India belongs as much to Muslims and Christians as it does to Hindus, then what the Modi government has done in the last four years is completely antithetical to what Gandhi stood for.”

Of all the issues dearest to Gandhi, interfaith relations are the most under threat in modern India, Mr Guha says. “Never before has there been such systematic persecution [of Muslims], aided by ruling party politicians. It would absolutely horrify Gandhi.”

At the National Gandhi Museum, the heartbeat installation is not the only contribution to the nation’s Gandhi celebrations. On Monday afternoon, the museum’s director A Annamalai unveiled what he called a “comprehensive” digital learning kit on Gandhi, encompassing the man’s own writings and books about him, video and audio recordings of Gandhi speeches and prayers, and audiovisual tours of his former homes.

The kits will be used in outreach programmes for disadvantaged schools – ensuring that the legacy of Gandhi continues to live on for generations to come.

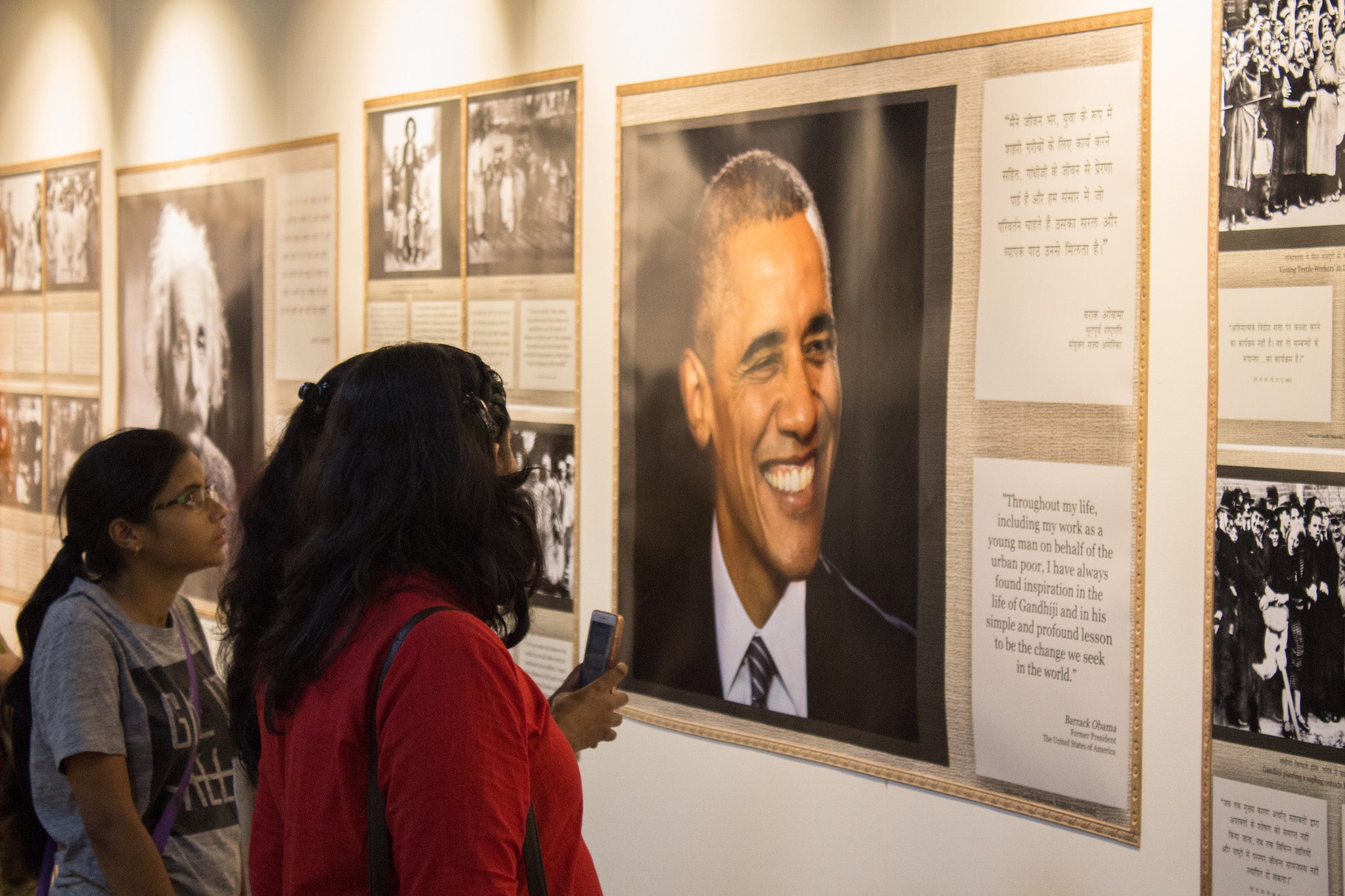

At the same launch event, the director of the Mahatma Gandhi Centre for Peace Studies, Professor Ramin Jahanbegloo, unveiled a new special exhibition showing photos of Gandhi in his last years alongside quotes from major world leaders talking about how Gandhi inspired them.

Professor Jahanbegloo says he believes that – though he may be the Father of the Nation for India – Gandhi has taken on an even bigger role in inspiring moral leadership in the rest of the world.

“I can define Gandhi’s legacy in two words,” he tells The Independent on a tour of the new exhibition. “Democratising democracies.

“Gandhi is now more relevant outside India than in India,” he said. “If we look around the room at the leaders featured here – Mandela, Obama, Martin Luther King – they all took the message of Gandhi and they made it their own.

“Gandhi’s message is very much alive. He taught us that you must listen, learn from others and only then can you lead. In today’s world, with leaders like Putin or Trump worst of all, there is no moral capital in politics. That’s why the world is suffering so much, we have leaders who do not understand the message of Gandhi.”

One of the first people to use the Gandhi museum’s installation to listen to his heartbeat is a woman whose mother, up until he died when she was 14, knew it very well first hand.

Sukanya Bharatram is Gandhi’s great-granddaughter. She tells The Independent that she does not see her great-grandfather’s legacy in terms of movements, governments or international politics.

“Mahatma Gandhi transcends all of that,” she says. “The search for Gandhi is everywhere, it is not restricted by boundaries of religion, of caste, of colour.

“The best way to commemorate Gandhi is through introspection, and self-criticism. He was constantly searching within himself. Anyone who is going through that process, if it is done with love and in the pursuit of truth, at some point this search will coincide with Gandhi’s.”

After listening to Gandhi’s heartbeat, Ms Bharatram says she does not believe it means any more to her than to anyone else. “Mohandas K Gandhi belongs to our family but Mahatma Gandhi – he is just as much a part of you as he is of me,” she says.

“My mother explained it best; she said that when Gandhi died, he evaporated. He’s in the ether now. In that sense he doesn’t belong to me or my family – he belongs to everybody.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments