The formula for fame and fortune in South Korea? Teach maths

Lecturers are going online, donning costumes and singing with celebrities to get their academic messages across - and making a lot of money in the process. But some politicians fear the pressure on children is too much

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Clasping his headphones and closing his eyes as he sings into the studio microphone while performing a duet with one of South Korea’s hottest actresses, Cha Kil-yong looks every bit the K-pop star.

But Cha is not a singer or an actor. He’s a unique kind of South Korean celebrity: a teaching star. And the song he sings with Clara, a Korean celebrity, in a video that wouldn’t be out of place on MTV? It was called “SAT jackpot!”

In the education-obsessed South Korea, Cha is a top-ranked maths teacher. But he doesn’t teach in a school.

He runs an online “hagwon” – or cram school – called SevenEdu that focuses entirely on preparing students to take the university entrance exam in mathematics.

In South Korea, teaching pays: Cha said he earned a cool $8m (£5.1m) last year.

“I’m madly in love with maths,” says Cha, looking the height of trendiness in his crimson shirt, trousers and tweed jacket, in his office in Gangnam – a wealthy part of Seoul famous for its conspicuous consumption and featured in the worldwide pop hit “Gangnam Style.”

It is hard to exaggerate the premium South Korea places on education.

It is a society in which you have to get into the right nursery, so that you can get into the right primary school, then into the right secondary school, and finally into the right university.

The last, of course, gets you the right job and, potentially, the right spouse.

There’s even a phrase to describe the Korean version of the US helicopter mother – “chima baram”, literally “skirt wind” – the type of parent who rushes into the classroom to demand a front-row seat for her child or to question teachers’ marking.

Many Korean families split and live on opposite sides of the world in pursuit of a better education: the mother and children live in the United States or another English-speaking country, to secure entry to a prestigious university (preferably Harvard, Oxford or Cambridge). The “goose father” continues working in South Korea, flying in to visit when he can.

All of this combines to make South Korea’s equivalent of the SAT pre-university exams the most important event in a young person’s life.

The vast majority of teen-agers do a double shift at school: they attend normal classes by day but go to hagwons for after-hours study. Increasingly, online hagwons are replacing traditional brick-and-mortar cram schools. The hagwons have become a £13bn industry.

This devotion to studying is credited with helping South Korea rank consistently at the top of the developed world in reading, maths and science. However, the latest rankings from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development also show that Korean students come last when asked whether they are happy at school.

South Korea also has the highest suicide rate in the developed world, which many suggest is related to a high stress focus on education.

Some politicians and educators are questioning whether things have got out of hand. But even parents opposed to this punishing system find it difficult to opt out – their children complain that they can’t keep up if they don’t go to a hagwon.

That is good news for instructors like Cha, who started teaching at a hagwon to pay his way through his PhD programme.

About 300,000 students take his online class at any given time, paying £25 for a 20-hour course (traditional cram schools charge as much as £385 for a course). He teaches them tricks for the timed exams, including shortcuts to solve a problem.

Asked what makes him stand out, Cha says: “Suppose you give the same ingredients to 100 different chefs. They would make different dishes even though they’re working with the same ingredients. It’s the same with a maths class. Even though it’s all maths and all in Korean, you can use different ingredients to come up with different results.”

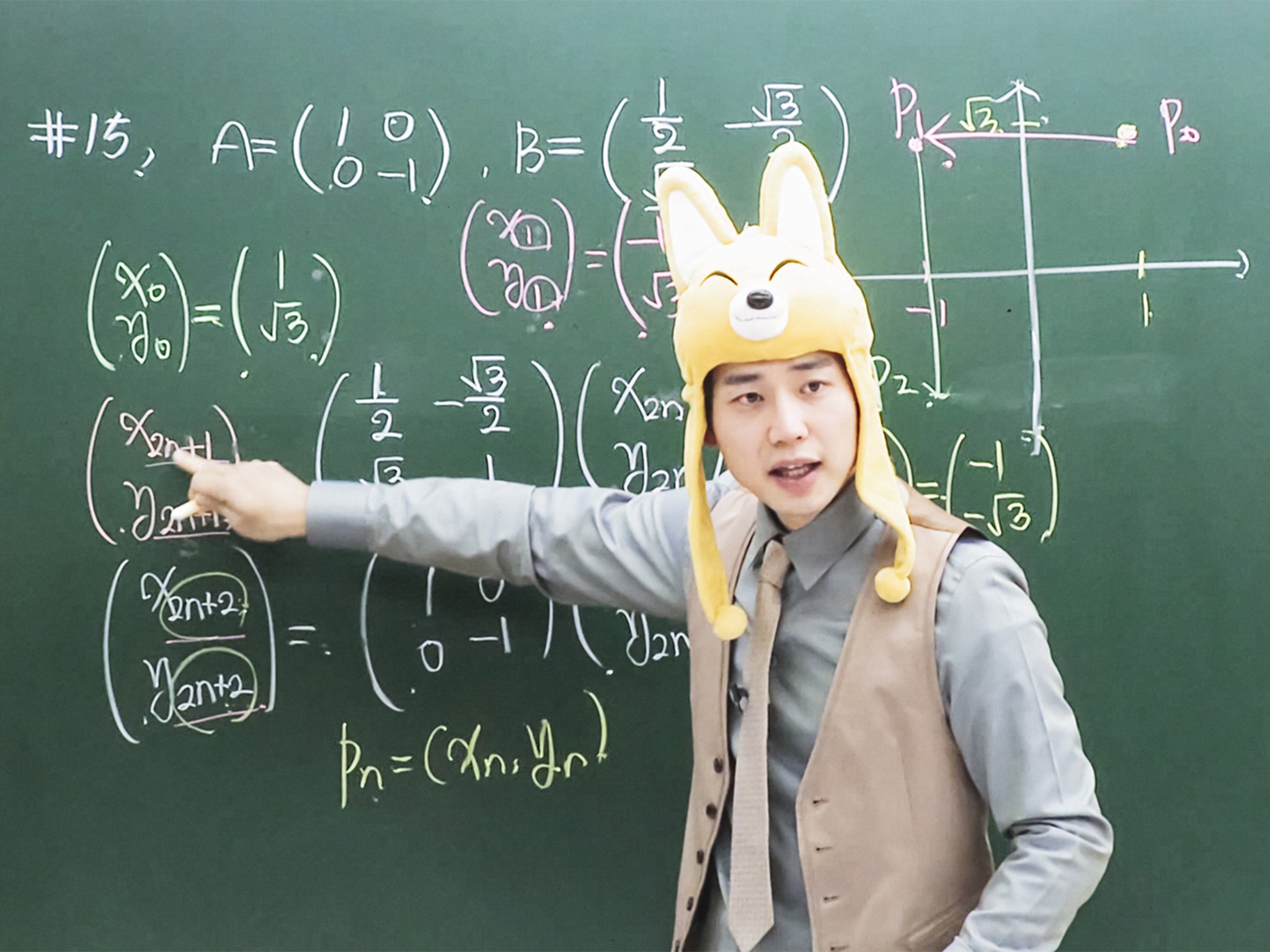

His studio is set up with a green chalkboard and desks. Behind the camera are piles of props – including a hippo, Batman masks and a gold sequined jacket. “You’re not only teaching a subject, you also have to be a multi-talented entertainer,” says Cha, declining to give his age and offering only that he’d been working for 20 years.

On exam day, he visits schools to offer encouragement to test takers. He also does television adverts, endorsing products such as a red ginseng drink meant to boost brain power.

Kwon Kyu-ho, a top-ranked literature teacher, also appears with K-pop stars and has a lucrative side business in celebrity endorsements, lending his name to a chair meant to help people study better.

Maintaining his position doesn’t require just good lessons. Kwon, 33, also gets regular facials and works out. He said some teachers even had stylists. “I always wanted to be a teacher, but I feel that regular school teaching has its limits. There is a certain way you have to teach,” says Kwon, whose lessons appear on the sites Etoos and VitaEdu. “And, of course, I’m making a lot more money this way.”

He won’t disclose how much he earns, only that it was “several millions” of pounds a year. The secret of his success, Kwon says, was finding the parts of tests that make most students stumble. He focuses lessons on those problem areas. This style of education has its upsides, he says.

“One of the benefits of private education is that teachers compete with each other,” he says. “We have money. We can invest in ways normal teachers cannot.”

As President Park Geun-hye promotes a “creative economy” as the key to taking South Korea to the next level in its development, many analysts say the country would do well to take a more creative approach to education.

Lee Ju-ho, who was Minister of Education until last year, is among them. “Late-night study could lead to problems in enhancing other skills, like character and critical thinking,” he says. “Hagwon is all about rote learning.”

He says all the problems stem from the university admissions procedures, which have been slow in looking beyond test scores to other criteria such as extracurricular activities and personal essays, as is common in many Western countries.

“We really need to change,” says Lee, now a professor at the Korea Development Institute’s School of Public Policy and Management.

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments