An increasingly belligerent China is reshaping the neighbourhood and its own future

The communist nation is increasingly falling out with its neighbours, who will keep a wary eye on events in Beijing during 2021, reports Mayank Aggarwal in Delhi

The year 2020 will be best remembered by people in most countries for the struggle to contain a deadly virus that originated in China.

But for several of China’s neighbours, the year has also seen a dramatic increase in fraught territorial conflicts with the communist nation.

The flash of violence on the Himalayan border between China and India has been perhaps the most visible example of Beijing’s increased assertiveness, a huge and deadly military standoff that has seen the forces of the two nations stand eye to eye for more than 200 days now.

Through the year, though, China has clashed in one way or another with all of the Philippines, Japan, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Nepal, Bhutan, Mongolia, South Korea and Kazakhstan.

China’s imposition of a strict new national security law in Hong Kong, and subsequent crackdown on the protest movement there, has worried others in the region. Taiwan, which China claims as its own territory, fears a similar fate amid ongoing threats from Beijing of a military invasion. In October, the Taipei government revealed it spent almost $900m (£670m) in the first nine months of 2020 scrambling its air force to respond to Chinese incursions.

And in many ways Australia is bearing the brunt of China’s bullishness, with its attempts to rejoin the Quad naval drills and calls for an international investigation into Covid-19’s origins punished by new trade tariffs designed to disrupt Australian exports.

In some ways this should have been expected, as China’s economy grows and it overtly seeks to challenge American hegemony. Harsh V Pant, professor of international relations at King’s College London, says it is normal for countries that are becoming increasingly powerful to begin flexing their muscles through a range of geopolitical actions.

He tells The Independent that most of China’s acts can be viewed through this prism, whether it is its negotiations with the US, its involvement in regional trade deals, its territorial disputes with neighbours or its dealings with Hong Kong and Taiwan.

Professor Pant adds that China’s actions, diplomatically and militarily, at the global level and also more regionally stems from the assumption that it is China’s moment on the world stage. “It has led to China being aggressive and assertive while being explicitly open about it” for the first time, he says.

Not everyone would agree with that characterisation, of course. Hu Xijin, the outspoken editor of the Communist Party-run Global Times and ally of president Xi Jinping, wrote in an article in September that most of China’s land disputes have been resolved through negotiation, not force, and the impression that it is “isolated” in the Asia-Pacific neighbourhood is wrong.

At the same time he admitted that China is still engaged in ongoing land and maritime disputes with India, countries around the South China Sea and Japan.

China’s current standoff with India in Ladakh is also not a one-off event unique to 2020. In 2017, the two were involved in a months-long standoff in Doklam – a small region at the trijunction of China, India and Bhutan.

Reports have also suggested Chinese border encroachments in some areas of Nepal, sparking alarm in India, even as Kathmandu has pursued closer ties with Beijing.

Dr BR Deepak, professor of Chinese Studies at Delhi-based Jawaharlal Nehru University’s Centre of Chinese and Southeast Asian Studies, says that China’s manoeuvres in the past two decades have seen it increase its influence dramatically in the South China Sea without firing a single shot.

“It is China's robust economy that has helped China increase its technological and defence capabilities. It has also helped China increase its influence with countries like Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Bhutan, Maldives and others who despite the fear of debt trap welcome China's investment – somewhere India has failed to live up to their expectations irrespective of its closer cultural affinity,” Dr Deepak says.

According to a June report by a group of US and European experts on China, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) has become considerably “more assertive, demanding, unyielding, confrontational, and punitive in its international posture”. They say this includes “wolf warrior” diplomacy, economic punishments, increased foreign propaganda and influence operations, mercantilist trade behaviour and a rapidly modernising military.

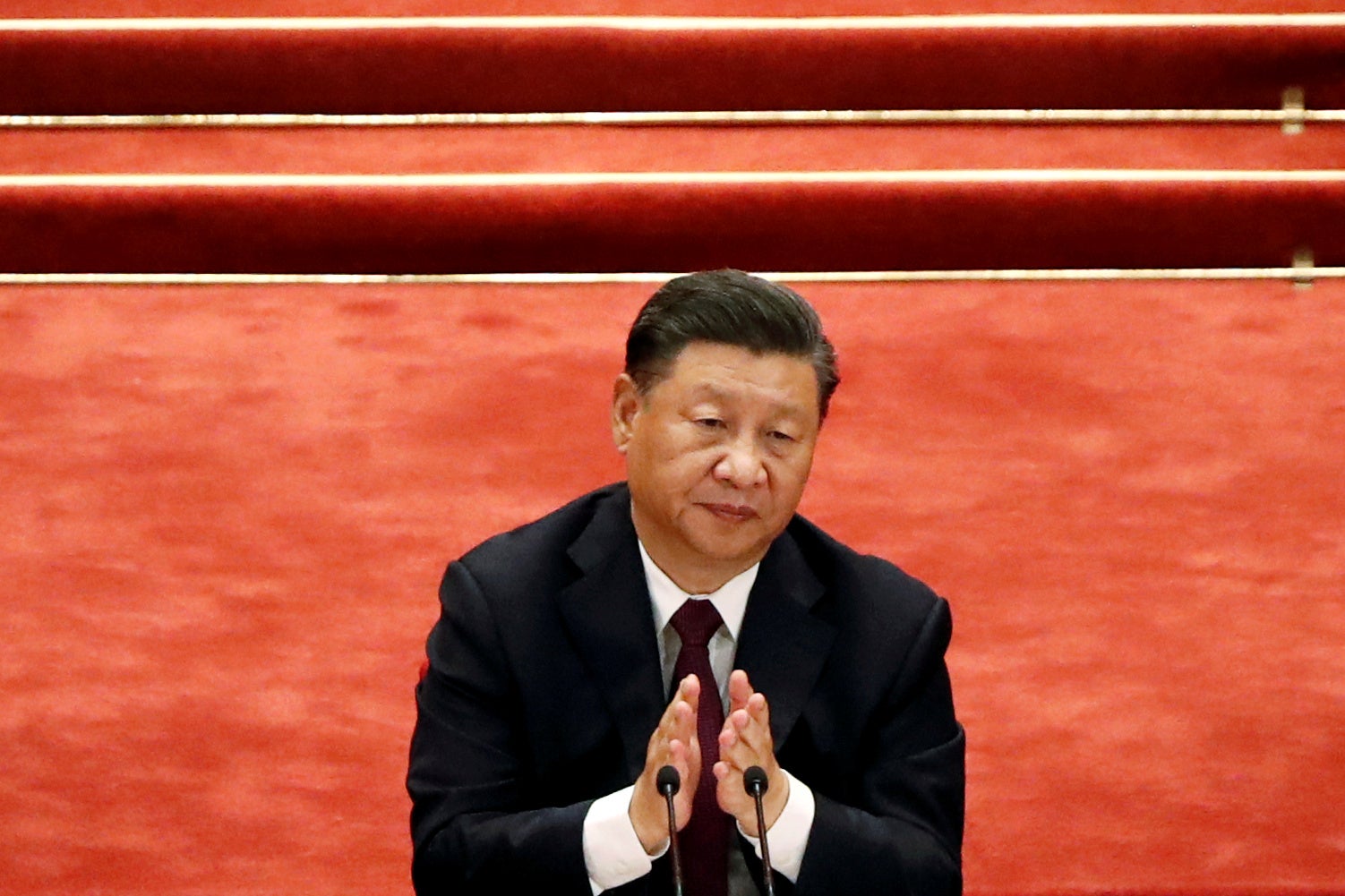

While these moves can be traced back decades – “the successful organisation of the 2008 Olympics could be a starting point”, suggests Dr Deepak – there is no question that they have accelerated following the unprecedented consolidation of power domestically with China’s President Xi.

Xi became the president in 2013 and, in 2018, his control on the CCP tightened enormously when the two-term limit for presidents was removed – effectively allowing him to remain president for life.

“Domestic consolidation of power and aggressive foreign policy approach are two simultaneous forces that need to be understood,” says Prof Pant. “The more he [Xi] centralises his power turning into an all-powerful supreme leader, the more aggressive and assertive he becomes in dealings on the global stage.”

Dr Deepak says that the unprecedented infrastructural development that was Xi’s main USP in his first term gave him the confidence to take China to the next level – in other words, after eradicating absolute poverty at home his next goal is to transform China into a prosperous modernised world power by 2035.

“For instance, before him, only 5,000 kilometres of the high-speed railway lines were built but during the last eight years, more than 30,000 km of high-speed railway lines connecting the remotest areas inside China has been laid down. All these factors contribute to the rise of Xi Jinping and his assertiveness on the global scale including the immediate neighbourhood.”

In addition to the international resistance to China’s muscular posturing, some experts argue that there are concerns within China as well, though people are afraid to speak out against Xi openly.

“He has purged a lot of his critics,” says Prof Pant. “In the early phase of pandemic, there was a disenchantment against his handling of the crisis but there is an absence of a mechanism to channel that.”

Moreover, the opening of so many fronts at once - all around China’s periphery – doesn’t necessarily reflect a successful foreign policy strategy, even if that is being used as a projection of strength, Pant argues. Xi will have his hands full in the coming years dealing both with the fire in China’s neighbourhood and pushback from the US at the same time.

A few days ago, a paper by Kalpit A Mankikar of the Observer Research Foundation, a Delhi-based think tank, had stressed that “as Xi fortifies his hold over the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the country, repressive policies in Tibet and Xinjiang and excessive curbs on academic freedom can pose potential political threats”.

“At the same time, issues like ecological degradation and widening wealth disparities may add to Xi’s challenges. How Xi and the CCP aim to navigate these flashpoints will have a significant bearing on the future of the country, the party, and the president himself,” says the paper.

It mirrors questions of many who are closely monitoring the developments as China readies itself for centenary celebrations of the Communist party in 2021 – which may also give signs of the policies China chooses for the decades ahead.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments