Afghanistan: Aid workers pull out in the face of Isis and Taliban threat, turning a healthcare revolution into a crisis

A five-hour trip by donkey to give birth, hundreds of thousands of children left unvaccinated: Afghanistan is a sick nation, 14 years after the US-British invasion heralded a new era of healthcare. Bilal Sarwary reports from Kabul

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.From dawn, the queues grow. Several thousand of the walking wounded wait patiently, hoping to flee for Pakistan, India and Iran.

Among the few perceived success stories of the American and British invasion of Afghanistan in 2001 was much-vaunted investment in health and education. But the long lines of Afghans outside embassies in Kabul this week paint a different picture, one of a nation in a healthcare crisis, rocked by a renewed Taliban threat.

In the face of attacks from the Taliban in Helmand and Kunduz provinces, many aid workers who provided a lifeline for thousands of Afghans have withdrawn. In Kunduz, the city where a US air strike hit a clinic run by Médecins Sans Frontières in October, the United Nations said aid workers were pulling back from the front line.

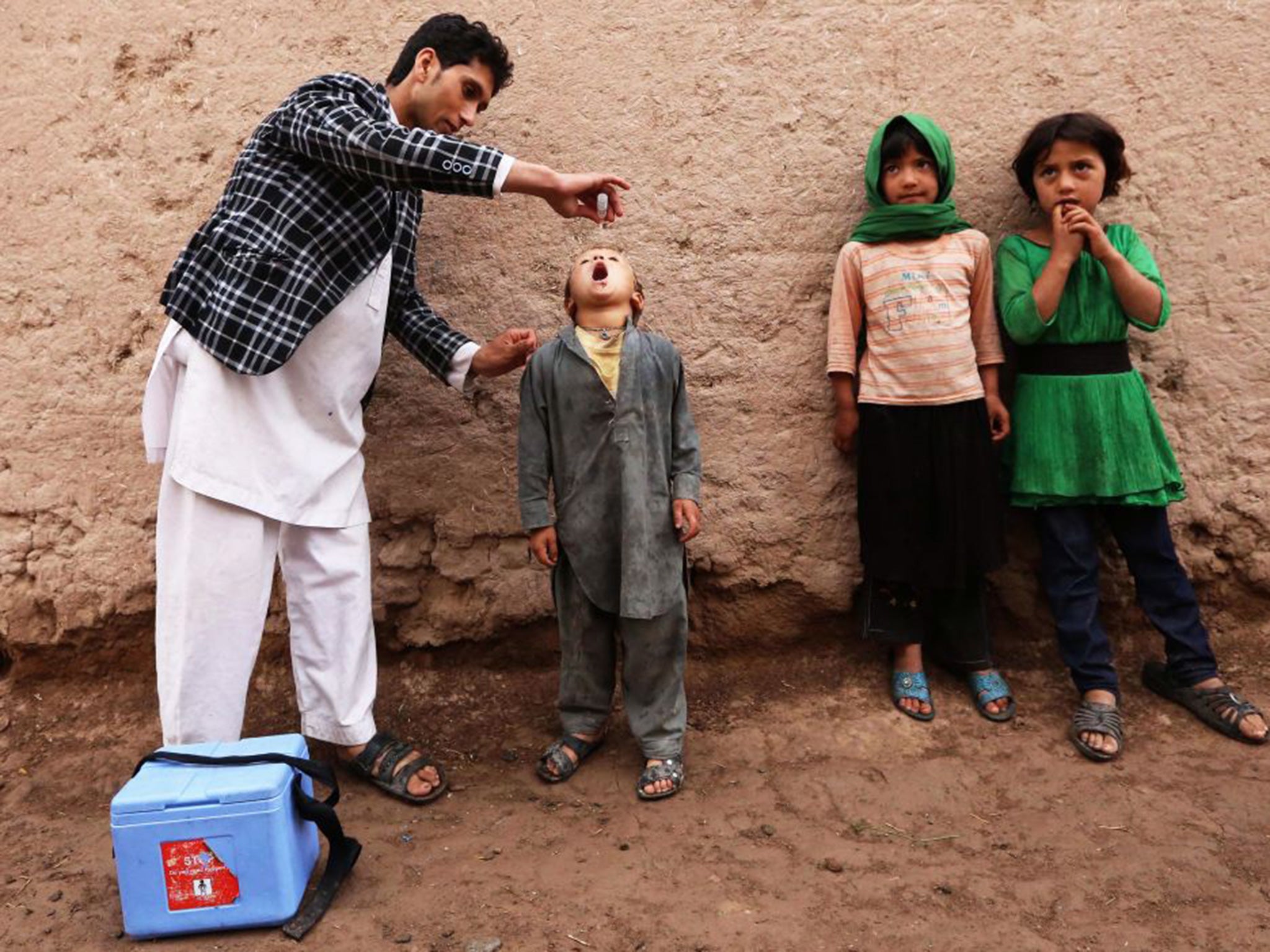

The Taliban is not the only threat. Isis, the jihadist group whose influence has extended beyond Iraq and Syria to Afghanistan, is now blocking government polio vaccinations across the country, telling residents that the Afghan government and the West are using health workers for “intelligence-gathering purposes”, or that the vaccine contains forbidden pork.

The Afghan ministry of health said that around 100,000 children had not been vaccinated in 14 eastern and southern provinces because of the group’s threats. Afghanistan and Pakistan are the only nations where polio remains endemic.

Only eight cases have been confirmed this year, compared with 108 in Pakistan.But on Monday, two vaccination volunteers who were visiting a house in Kandahar – a woman and her teenage daughter – were shot dead. A local health official, Abdul Qayum Pukhla, told Reuters: “[It] was the last day of the campaign and as the workers were leaving a house, the gunmen opened fire and fled.”

Some of the most remote areas have been left with virtually no doctors, with healthcare workers unwilling to risk their safety for poor pay.

“We have a district in Badakhshan, Ragh, which is the reason Afghanistan has the highest infant mortality rates in the world,” said Dr Nilofar Ibrahimi, a member of parliament from Badakhshan province and a gynaecologist.

“This is a crisis. We have another district, Tagab, where 20,000 people have only a nurse. There is not a doctor there. The problem is corruption of the past 14 years and a lack of a vision. And then you have to think about lack of support for doctors – from salaries to insurance.”

Last year, a British government report on the UK’s progress in Afghanistan lauded healthcare success. More than half of the population had access to primary healthcare, compared with 9 per cent in 2003, the report said. Maternal mortality had halved and life expectancy was at its “highest ever” level.

In Kijran, in Daykundi province, on the border of Helmand and Uruzgan, Bibi Khadijah, a mother of eight, was forced to travel for five hours by donkey to see a midwife when she gave birth to her youngest daughter. “I am one of the lucky ones,” she said. “For basic and simple diseases there are no doctors or medicine. When children have diarrhoea or chicken pox, we can’t get treatment.”

Security is only part of the problem in Afghanistan, and investment only part of the solution. “Investment in health has taken place. But this doesn’t help. Corruption was the reason for the problems in the health sector,” the chairman of the parliamentary health committee, Dr Enayat Ibrahimi, told The Independent: “There has been mismanagement in the past 14 years.”

An investigation by the US-based Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (Sigar) has questioned where $210m of US aid money to the Afghan ministry of public health has been spent, after co-ordinates provided by USAID for the location of health clinics turned out to be empty.

Haji Baaz Mohammad, a 68-year-old farmer in the eastern province of Nuristan, where there are no government hospitals, despite funds being allocated for one in 2010, said: “There is only one surgeon in the entire province of at least half a million people. Our patients die on donkeys and mules on their way to Pakistan. Despite all the aid, people in Nuristan are dying because of lack of medicine and doctors.”

There are some success stories, however. Fatima Gailani, 61, has become a ray of hope for children, some of whom have less than six months to live. The children she helps suffer from a congenital heart defect, commonly referred to as a “hole in the heart”, and need surgery to survive. Their only hope is the money Ms Gailani and her team are trying to raise at the Afghan Red Crescent compound in the modest Kabul neighbourhood of Afshar-e-Silo.

“There is increasing incidence of the disease in Afghanistan,” Ms Gailani said. The daughter of a prominent Mujahideen leader, Ms Gailani spent much of her life in exile, and moved back to Afghanistan after the fall of the Taliban.

For her, the biggest challenge for the Afghan Red Crescent is raising funds. “There is this perception that people in Afghanistan are not willing to spend on a good cause. We wanted to change this perception,” she said, adding that the former President, Hamid Karzai, had called several prominent Afghan businessmen, asking them to donate. His successor, Ashraf Ghani has asked the Indian ambassador in Kabul to facilitate the treatment of Afghan children in his country.

“The Afghan Red Crescent has managed to fund the treatment of 3,320 children since 2008,” Ms Gailani said. “But there are 4,000 children still in need of care. Of these, 1,600 have six months or less to live if surgery is not carried out soon. We can’t afford delays. Afghanistan will have to help Afghanistan.”

Total casualty figures for Afghan security forces have not been published, but are said by Nato sources to be 28 per cent higher than in 2014, when the toll was around 5,000.

The Afghan forces have had a tough year on the battlefield, having to fight the insurgents alone for the first time, following the drawdown of international combat troops at the end of last year. The Taliban has used this to step up its offensives across the country.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments