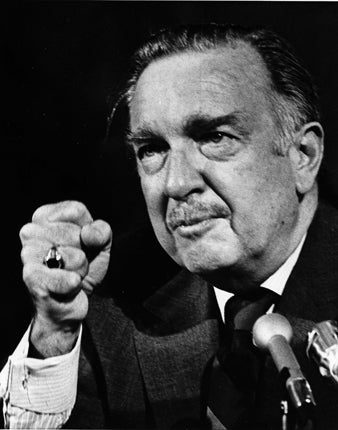

Walter Cronkite: That's the way he was

Walter Cronkite, the TV news pioneer who died on Friday, was in his time perhaps the most famous man in the US. Rupert Cornwell looks back on his career

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There will never be another like him, for a simple reason. There cannot be. Walter Cronkite, the legendary American television journalist, who died on Friday night, was a titan from a vanished era, when the three broadcast networks ruled the airwaves unchallenged.

It is inconceivable that another TV news anchor could ever be to Americans what Cronkite was during the 1960s and 1970s: a sort of national family uncle, wise, reassuring, understanding, a man they could trust to tell them the news – to borrow his own sign-off line from the CBS Evening News – the way it was.

The clout of network TV news back then is hard to grasp for anyone reared exclusively in the modern universe of the internet, blogs, and 24/7 cable news channels. CBS Evening News, which under Cronkite overshadowed the rival programmes at NBC and ABC, had a viewership of some 20 million, almost as much as the combined audience of the three shows today, when the national population is half as large again.

At the height of his career, Cronkite was arguably the most famous and influential individual in the US. The moment when he told his countrymen of the death of John F Kennedy, his composure for once crumbling, his eyes misting with emotion as he slowly took off and replaced his black-rimmed glasses, is seared into America's collective memory scarcely less deeply than the dreadful images from the motorcade itself. "From Dallas, Texas, the flash, apparently official," he intoned. "President Kennedy died at 1pm Central Standard Time."

Instinctively, Cronkite was what today would be called a liberal. On screen, however, impartiality was his trademark, an impression amplified by his deliberately slow delivery and taste for understatement. At one point he was voted the most trusted man in the country – a point brought home to President Lyndon Johnson in 1968 with the most momentous consequences. After the Vietcong's Tet offensive that January, Cronkite went to South Vietnam for a first-hand look at what was happening. His TV editorial concluding that the war was a stalemate, and that a negotiated settlement was the only way out, shocked Johnson, as it laid bare the infamous "credibility gap" between the administration's rosy depiction of the war, and the ever more obvious reality.

"If I've lost Cronkite, I've lost Middle America," LBJ is said to have remarked to an aide. Within weeks, the President announced that he would not seek a second elected term, and vowed to search for a negotiated peace – just as Cronkite had urged.

But Americans adored him, too, for a boyish excitement, never more visible than when he covered the Apollo 11 moon mission in 1969. "Man on the Moon ... oh boy ... whew, boy," were his words as the lunar module Eagle touched down. "There they sit on the Moon ... by golly." At Cronkite's last national convention in 1980, when the Democrats renominated Jimmy Carter, the delegates chanted "Walt-er, Walt-er" with a passion that eclipsed their feelings for the incumbent president. His last evening in the anchor's chair, on 6 March 1981, was a major news event in itself. Weeks before, T-shirts appeared with the legend, "Oh my God, what are we going to do without Walter Cronkite?" It was a joke, but not entirely.

His career amounted to a history of the American news business in the middle and late decades of the 20th century. From his high-school days in Texas, he wanted only to be a journalist. After working for a year at the Houston Post, and then as a news and sports announcer for radio stations in Kansas City and Oklahoma, Cronkite joined the United Press, then the pre-eminent US news agency. Soon he was a hardened war reporter, covering the allied bombing campaigns against Germany, the 1944 Normandy landings and the Battle of the Bulge. After the Nazi defeat, he was UP's chief correspondent at the Nuremberg war trials, before spending two years in Moscow, as the Cold War began.

In Moscow, he resisted the initial attempts of Ed Murrow, the bureau chief of CBS radio and future patron saint of the network's entire news division, to recruit him. But in 1950, back in the US, Murrow and CBS got their man, and Cronkite's television career began. The medium was then in its infancy, but Cronkite quickly realised it would soon overtake radio and print journalism to become the prime source of news for Americans, and a crucial factor in its politics. Even early on, it was plain that his natural, avuncular style (which today would probably be derided as pompous) connected with viewers. By 1962, CBS had named Cronkite as the first of the newfangled "anchormen" for its flagship television evening news programme. In September 1963, it became the first network to extend the usual 15-minute programme to half an hour, launching the first expanded format with an interview with JFK. Just two months later, Cronkite was covering the President's assassination.

He was 64 when he was eased out of his evening news chair to make way for the young Dan Rather – a retirement he regretted almost the instant he stepped down. He continued to make programmes for some years, but always resented the way that he had been treated. If CBS seemed to forget him, however, Americans never did, and to younger generations of reporters and anchors he was a father figure.

In retirement, his liberal colours showed more clearly. Cronkite was a fierce opponent of the 2003 Iraq invasion, insisting that had he still been behind the anchor's desk he would have condemned George Bush's intended war just as he had condemned LBJ's war 35 years before. The Cronkite era, though, could never return. In his heyday, he was the first true celebrity newsman, more famous than the politicians and stars he covered. But he was also a consummate professional, fiercely competitive and always mindful of his start in wire journalism, then as now the coalface of the news industry. "I want to win," he said once. "I not only want to win, I want to be the best." He was.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments