USS Oklahoma: The first US victims of the Second World War are finally coming home

The US is using DNA to identify sailors who died in the attack on Pearl Harbour

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Inside an old aircraft factory, behind the glass windows of a pristine laboratory, the lost crew of the USS Oklahoma rests on special tables covered in black foam.

Their bones are brown with age after 50 years in the ground and, before that, months entombed in their sunken battleship beneath the oily waters of Pearl Harbour. Legs, arms, ribs, vertebrae. Some have blue tags tied with string, identifying the type of bone. Some have beige tags, indicating that experts also want samples for DNA testing.

They are the unidentified remains of hundreds of American sailors and marines who perished 74 years ago when Japan launched the surprise air attack on Hawaii that finally brought the US into the Second World War. Now, seven decades later, the government is trying to put names to those who died when their ship was sunk that fateful December Sunday morning.

Over the past six months the bones have been exhumed from a cemetery in Hawaii to be brought to a new laboratory in Nebraska for scientists to begin the task. The goal is to send the remains of those who died back home. “It’s important for the families,” said Carrie Brown, an anthropologist with a newly created agency, the DPAA, which is responsible for accounting for those captured, killed or missing in action. “For a lot of people, it’s an event that happened in their family history.

“We need to get these guys home. They’ve been not home for too long.”

The USS Oklahoma had a complement of about 1,300, including 77 marines. Its loss of life – a total of 429 sailors and marines – was second only to the 1,100 lost on the USS Arizona, whose wreck remains a hallowed Pearl Harbour historic site.

Thirty-two were rescued by intrepid crews who heard them banging for help, cut into the hull and made their way through a maze of darkened, flooded compartments to reach them. Others managed to escape by swimming underwater to find their way out. A few managed to escape through tiny port holes – pushed by brave comrades who couldn’t fit or were determined to let others go first. One who made that sacrifice were a Catholic priest, Lieutenant Aloysius Schmitt, the ship’s chaplain. Father Schmitt’s corroded chalice and water-stained Latin prayer book were found in the wreckage.

Among others who died was Machinist Mate Eugene Eberhardt, of Newark. His niece, Joan Roberts, 78, of Rockport, Massachusetts, said: “For years on Memorial Day we bring out his picture and toast him. Everybody loves him, and we have loved him forever.”

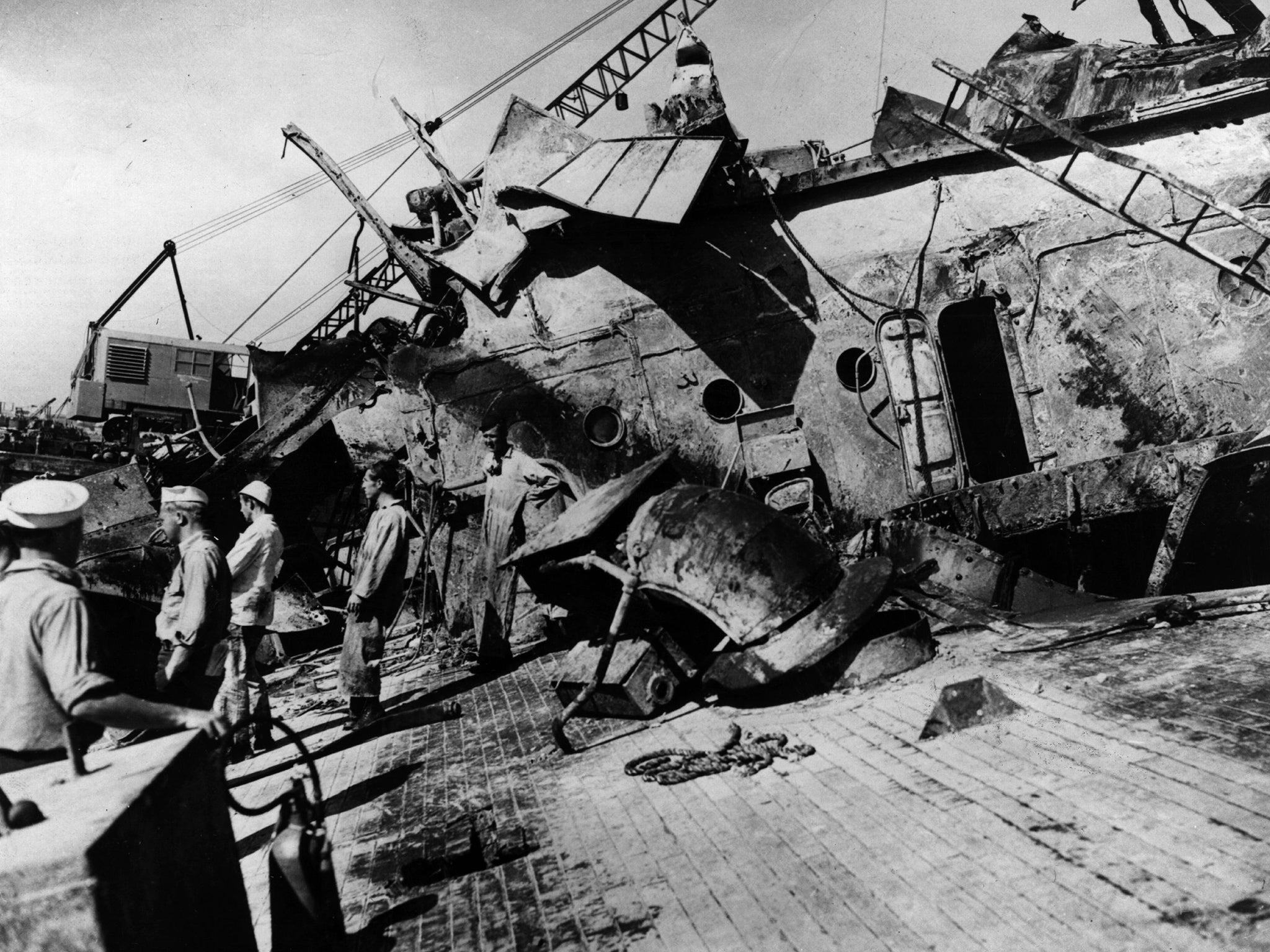

In the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbour, the handling of the crew’s remains suffered error, confusion and poor record keeping. Most were retrieved during the long salvage operation, especially after the Oklahoma was righted in 1943, but the bodies had been reduced to skeletons. By 1944, the jumbled remains, still saturated with fuel oil, had been buried as unknowns in Hawaii.

In April, the Pentagon decided to exhume and identify the Oklahoma’s 388 “unknowns” – using dental and medical records and gathering DNA samples from the crew’s relatives. Some 61 rusty coffins from 45 graves were found each to contain several bundles of bones, often mixed up.

Debra Prince Zinni, a forensic anthropologist involved in the project, said they now had the techniques needed to carry out the project, but admitted it would take years to complete. “It is a very large task,” she said.

Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments