‘I knew who I could go to’: How Tim Walz gave his queer high school students a refuge

Before he was Kamala Harris’s running mate, the Minnesota governor was a geography teacher, coach and faculty adviser for a gay-straight alliance at Mankato West High School. His former students tell Alex Woodward about their unlikely ally, and why dozens are now campaigning for him

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A straight, football-coaching national guardsman wasn’t the LGBT+ ally that Seth Elliot Meyer expected.

But Meyer, who came out as queer in his freshman year of high school in 2000, admits he was wrong about Tim Walz.

“I just sort of naively believed that someone who was a big, masculine dude with a deep voice was never someone who’s going to be on my side,” Meyer says.

“As much as those younger students who were courageous enough to be out in those years, it was just as important to have those very kind of ‘normal,’ strong, straight, masculine allies backing us up.”

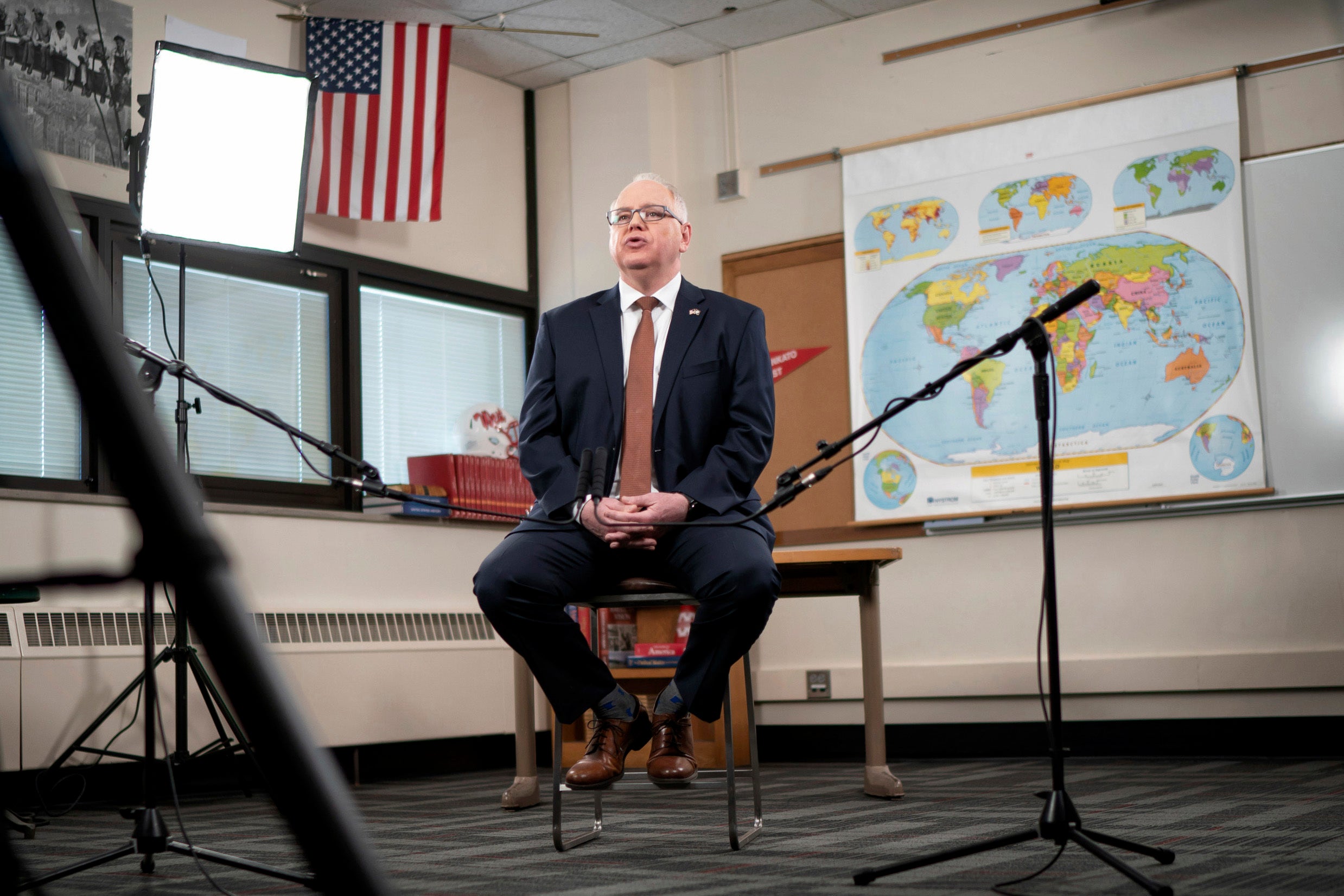

Before he was governor of Minnesota, before he was a member of Congress, and before he was a candidate for the next vice president of the United States, he was “Mr Walz,” a geography teacher at Mankato West High School, roughly 80 miles south of Minneapolis.

In 1999, Walz agreed to be the faculty adviser for the school’s first ever gay-straight alliance (GSA).

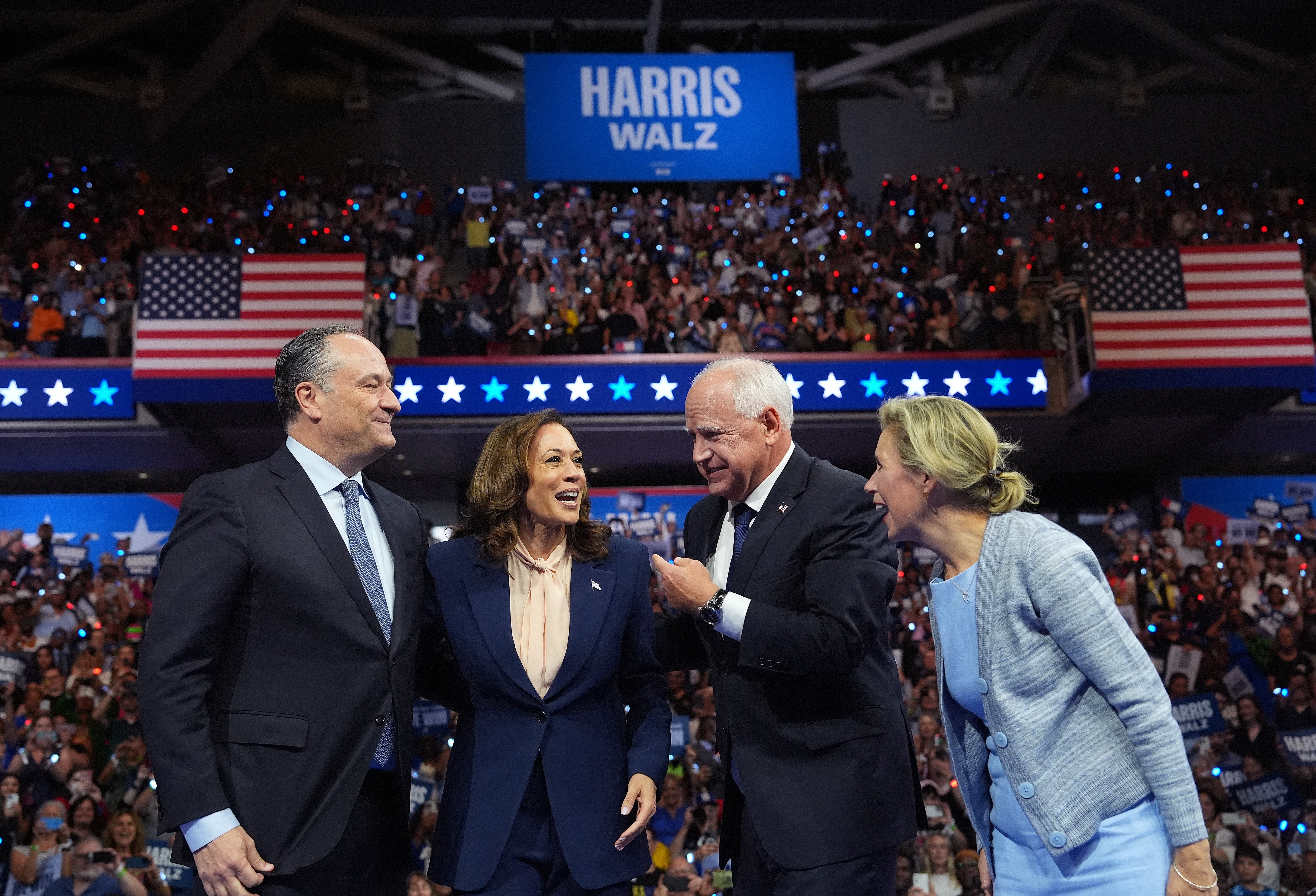

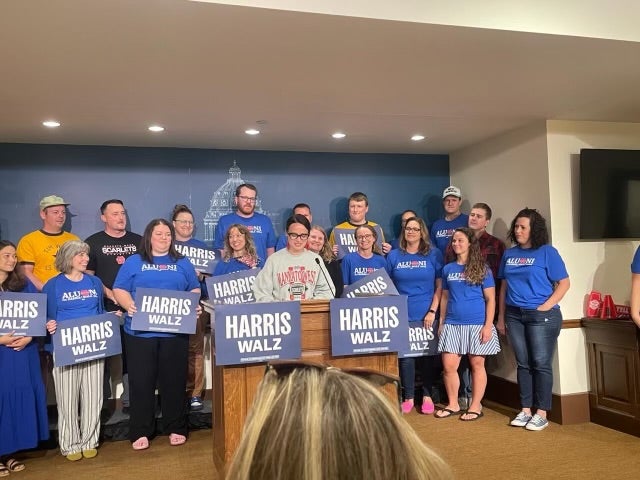

Walz and his wife Gwen, who also taught at the school, were a refuge for their LGBT+ students, alumni tell The Independent. Dozens of those former students are now campaigning for him to reach the White House.

In 2018, Walz told the Minneapolis Star Tribune that he felt it was important that he served as a GSA faculty adviser because “it really needed to be the football coach, who was the soldier and was straight and was married”.

There are now roughly 4,000 such groups, now known as gender-sexuality alliances, across the country.

“He was totally fine being a dude who would say, ‘Why the hell aren’t we all treated equal?’” Meyer, 38, tells The Independent.

“A lot of people have talked about how he’s genuine or not phony, and that’s true, but I don’t think that’s quite specific enough,” he says. “He just sounds like a human being before he sounds like a politician.”

At a Philadelphia rally earlier this month, Kamala Harris introduced her running mate by telling supporters how an openly gay student had asked Walz to serve as the group’s faculty adviser.

That student was Jacob Reitan, now a disability rights attorney and LGBT+ activist in Minnesota.

On his first day in Gwen Walz’s English class in 1997, the teacher “stood up and said that this was a safe place for LGBT students,” Reitan told MSNBC.

“It meant the world to me,” Reitan said. “I had never heard a teacher from the front of the classroom talk about gay and lesbian issues. My heart was literally beating out of my chest.”

In his junior year, Reitan and Amanda Hinkle, a senior at the time, made a banner to promote an “anti-oppression week,” with students using each day to recognize human rights abuses targeting race, religion, women’s rights, children and sexual orientation.

Hinkle wrote in her high school journal, pages of which she shared with The Independent, that students threatened to leave school if they learned about LGBT+ issues, and “kids were tearing down signs that said stuff about gay tolerance”.

Mankato West’s GSA started small, and the size and membership ebbed and flowed over the years. After founding the group in 1999, Reitan became something of a “gay legend” among LGBT+ students who joined the school in the years that followed, according to Micah Kronlokken.

“As a teenager, you’re like, ‘Oh God, if I joined the GSA, that means that everyone’s gonna think that I’m gay and know that I’m gay, so I can’t do that,’” Kronlokken tells The Independent.

Walz, however, was a “safe person, and you knew that if you needed something, you could go to him, and he could help you with it”.

“He understood that high school students are teenagers and need to be cared for,” Kronlokken says. “They can also grow by being treated a little more like adults and trusted to have tricky conversations, and that high school is a microcosm for our world at large.”

Walz coached Kronlokken in track and field in seventh grade, when he was “a young, closeted queer kid” more interested in music and the arts. (His parents bribed him into sports with a PlayStation.)

At one practice, Walz kept pace alongside him to ask him about his life and lessons he had learned from Chariots of Fire, a film that both Walz and Kronlokken loved. Two years later at Mankato West, Walz was an immediate friendly face in the hall.

“He just has this insane memory for people,” Kronlokken remembers.

Meyer attended his first GSA meeting in ninth grade in the fall of 2000 along with the handful of other group members, though he was scared he would be bullied.

“You knew who your peers were and who your allies were among both students and faculty, and that’s when I really started to understand just how much of an important role that Mr and Mrs Walz played,” Meyer says.

“I knew that if I was having a hard time and needed to talk to someone, or if someone was giving me a hard time, and I needed someone to defend me, I knew who I could go to.”

If Reitan and others hadn’t started the group in 1999, “I don’t want to imagine what my high school experience would have been like,” Meyer says.

That welcoming message stands in stark contrast to a wave of Republican-driven policies targeting LGBT+ students, faculty and school staff, including legislation inspired by Florida’s so-called “Don’t Say Gay” law taking aim at school discussion of LGBT+ people and issues. A lawsuit settlement earlier this year clarified that the law cannot be used to break up campus groups like GSAs.

Nearly 500 bills targeting LGBT+ people, including dozens of bills targeting students and young trans people, were filed in state legislatures this year, according to the Human Rights Campaign.

Walz left Mankato West in 2006 to run for Congress, where he served until 2019.

The Walzes made sure that “every kid felt like they had a place, that they had community”, Hinkle says.

When Hinkle designed a set for a school production of the two-act play The Nerd, which called for a staircase to a second level in the script, Walz built it.

“He literally made my dreams come true,” says Hinkle, who graduated from the school in 1999 and is now a theater educator in New York. “This was the biggest thing that ever happened to me in terms of trying something, being encouraged by teachers to do it, and seeing it actualized.”

Richelle Norton, an art teacher who graduated from Mankato West in 2001, spent hundreds of hours with the Walzes during her junior year, when Tim Walz taught global geography and Gwen Walz taught advanced composition, American literature and an ACT prep course in the evenings.

“They were really like the school mom and dad,” says Norton, who launched the Mankato West Alumni For Walz group.

“You don’t have to ask who the former Walz students were,” she said at a campaign launch event on August 14, while wearing a gray Mankato West football championship sweatshirt from 1999. “We will tell you, and we will not stop.”

Meyer is now a teacher in Atlanta, where he advises the school’s own GSA.

His students reported an increase in bullying during the city’s Pride in October. He shared with them what he learned as a scared teenager in Minnesota: “You didn’t do this just for you.”

“The message that I got — to bring this full circle to my high school and Mr Walz and the people who are visible allies — is it’s not about scoring political points,” he says. “It’s about showing people they can be comfortable being who they are.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments