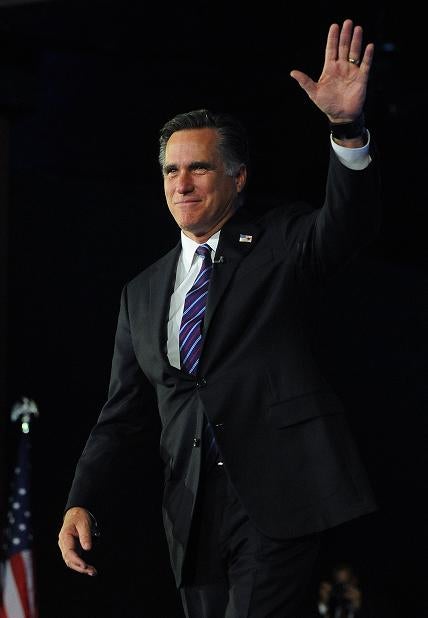

Romney's belief in himself never wavered

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Mitt Romney ended his Election Day sprint believing that, in the end, he waged the campaign he always wanted.

At this moment of make-or-break anticipation, Romney was serene and contemplative. Jetting to two more battleground states Tuesday, betting that one last visit might push him over the edge in the razor-sharp contest, he sat thinking. His eyes were closed, his chin resting on his clasped hands and his legs stretched out before him. One aide described it as a prayerful position.

Then Romney pulled out his iPad. "I just finished writing a victory speech," he later told reporters aboard the Romney plane for its final flight. "It's about 1,118 words."

What about a concession speech?

"I've only written one speech at this point," the would-be next president said.

Romney wasn't entertaining any what-ifs. Not on this day. He thought the White House would be his. That sense of destiny was reinforced when he landed at the Pittsburgh airport for an unannounced afternoon visit to discover hundreds of fans cheering him on from a faraway parking garage.

"Intellectually I've felt that we're going to win this, and I've felt that for some time," Romney told reporters. "But emotionally, just getting off the plane and seeing those people standing there — we didn't tell them we were coming. We didn't notify them when we'd arrive. Just seeing people there, cheering as they were, connected emotionally with me."

This is how Romney wanted to end his campaign. To get here, he followed a sometimes tormented path. He lurched to the right to survive a bruising primary. He faced painful scrutiny of his business career and personal wealth. And now, advisers said, he feels satisfied that he finished the campaign not as Mitt the "severe conservative," nor as Mitt the out-of-touch plutocrat, but as Mitt the middle-of-the-road problem solver.

"We're talking about the moderate Mitt, the guy who makes things happen, who walks in a room and tries to work out a deal, and it makes him feel better that we're not talking about this kind of odd guy who's hard to relate to," said Tom Rath, a longtime adviser.

Romney thought that if he won, he would win it by being himself. And if he lost, he would go out on his own terms.

Romney also thought that to achieve victory, he should make one last push. He rearranged his schedule at the last minute to make a final appeal to blue-collar voters in Pennsylvania as well as Ohio, the must-win battleground state where polls heading into Tuesday showed him lagging behind Barack Obama.

But first he had to vote. Obama had voted days ago, the first president to take advantage of early voting, but not Romney. He showed up with his wife, Ann, at their polling precinct near their home in Belmont, Mass., next to the soccer fields where he goes to watch his grandkids play on weekends.

It took Romney just a couple of minutes to complete his ballot. Asked whom he voted for, Romney didn't say, exactly. "I think you know," he said with a smile.

Then he got to work. Romney flew to Cleveland, where he visited a campaign office to buck up volunteers. "This is a big day for big change," Romney told them.

Then he and his running mate, Rep. Paul Ryan, Wis., stopped for lunch at a Wendy's. The former Massachusetts governor, parodied as an out-of-touch elitist, chowed down on a quarter-pound burger, chili and a Frosty — trying to demonstrate his Everyman sensibilities, even if it was after many voters had already gone to the polls.

Why Wendy's?

"We figured because Wendy's was invented in Ohio," he said, "what better place to get lunch than Wendy's, right?"

All day Tuesday, friends e-mailed Romney to say they were proud of the race he ran. And as he flew home to Boston, he could watch the sun setting out his window. His work for the day — and for this long, tumultuous chapter in his career — was finished.

"I feel like we've put it all on the field," he told reporters. "We've left nothing in the locker room. We fought till the very end."

When he touched down in Boston, Romney's Secret Service detail ferried him to his suite at the Westin, where he reunited with his family, a tight-knit clan of 30. They ate chicken and meatloaf and watched the television networks start to call the states.

There went Pennsylvania, hopes of an upset dashed. And Michigan, Romney's beloved Michigan — that one fell into Obama's column pretty quickly. Florida was tight, maybe too tight for the Republican who had thought he was pulling away there in the final weeks.

Then came the tough blows. New Hampshire, his adopted home state where he launched his campaign 17 months ago and staged his final rally Monday night to close with a deafening rally. Gone. Iowa, the prairie state that bedeviled him in the caucuses but that he was so sure he would win on Tuesday — Obama.

A couple of hours earlier, holding his 50th and final media availability of this campaign, Romney was talking about his transition, about appointing a Cabinet and getting to work. He said he might get a Weimaraner puppy when he moves to Washington.

In the end, though, his focus turned instead to his concession speech. Shortly before midnight, he assembled his motorcade to head to a ballroom full of supporters. The White House, he had found out, was not his destiny.

---

Felicia Sonmez in Boston contributed to this report.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments