Secret plans could give US president emergency powers to shut down the internet, report says

Murky Cold War orders that granted presidents sweeping emergency powers have never become public, but adjacent documents help piece together what the commander-in-chief may be able to do in certain circumstances

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new analysis of documents from the War on Terror era has indicated that the emergency powers granted to the president during the Cold War could allow the commander-in-chief to take shockingly drastic steps without oversight during an emergency – including turning off all electronic communications.

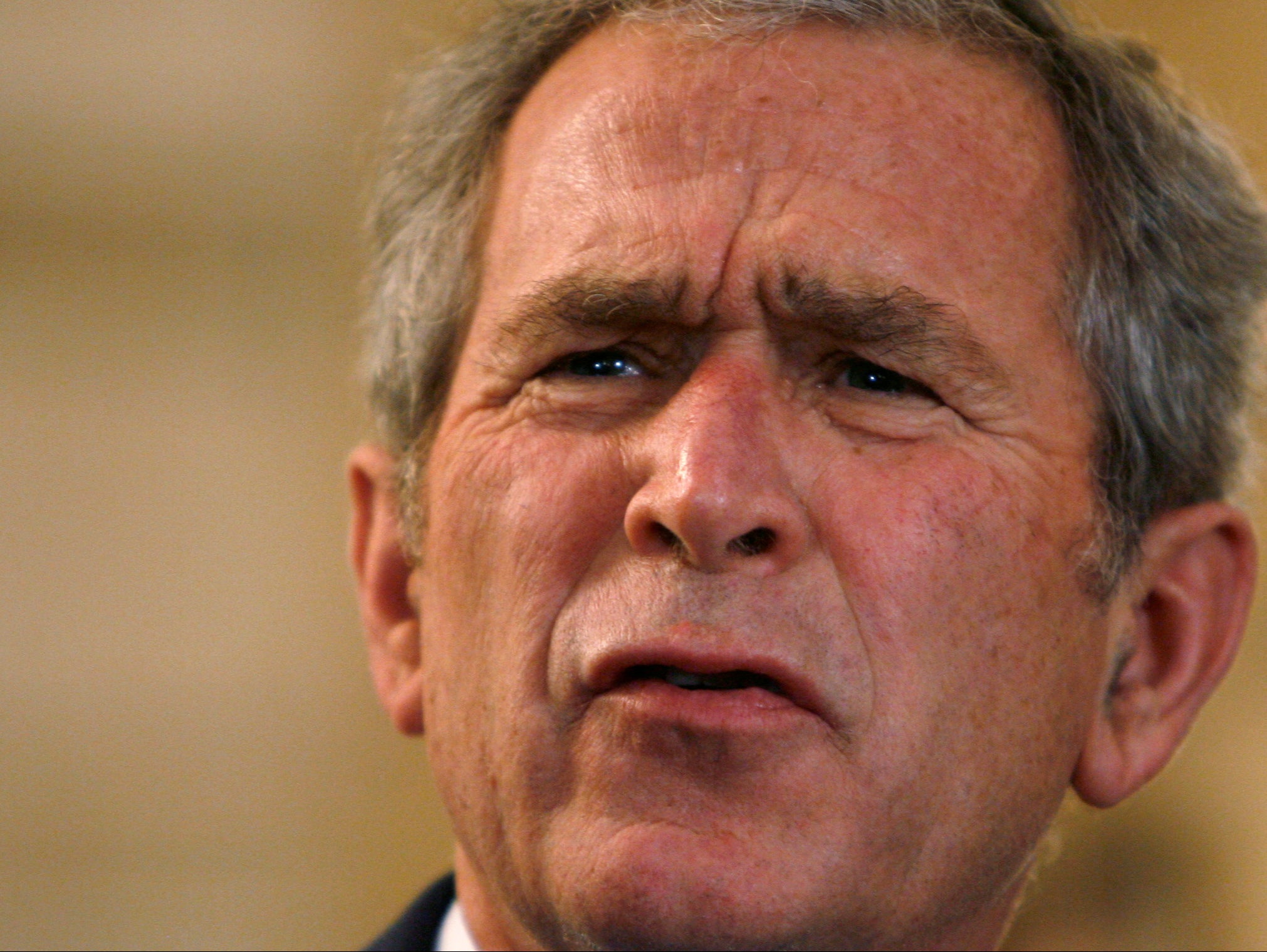

Analysed by the nonpartisan Brennan Center for Justice, the documents in question date from the administration of George W. Bush, and are the product of senior staffers’ efforts to refresh the secret Eisenhower-era plans made to ensure that the executive branch could ensure continuity of government in the event of nuclear war.

Though their purpose and existence is well known, these plans, known as “presidential emergency action documents” (PEADs), have largely remained secret since they were first drafted in the early Cold War era.

As spelled out by the Brennan Centre’s investigation, however, it has long been suspected that PEADs gave the president the authority to take extreme measures to close down national institutions and remove civil liberties – “to suspend habeas corpus, detain ‘dangerous persons; within the United States, censor news media, and prevent international travel.”

According to the centre, which secured details of the Bush administration’s review via freedom of information requests, the War-on-Terror-era staff looking into the extent and limits of the PEADs and adjacent documents found them to be “very broad” – and in particular one that could theoretically allow the president to close down the internet.

“At least one of the documents under review,” write the centre’s investigators, “was designed to implement the emergency authorities contained in Section 706 of the Communications Act. During World War II, Congress granted the president authority to shut down or seize control of ‘“any facility or station for wire communication’ upon proclamation ‘that there exists a state or threat of war involving the United States’.

“This frighteningly expansive language was, at the time, hemmed in by Americans’ limited use of telephone calls and telegrams. Today, however, a president willing to test the limits of his or her authority might interpret “wire communications” to encompass the internet – and therefore claim a ‘kill switch’ over vast swaths of electronic communication.”

By the time the review in question was completed, the Bush administration had already faced years of criticism over its dramatic expansion of the government’s ability to circumvent previously standard practices when it came to the arrest and detention of suspects and the surveillance of everyday Americans.

Along with the increased use of torture and “extraordinary rendition” – the practice of abducting suspected terrorists in other countries and transporting them via secret flights to detention facilities beyond US borders – the administration was also heavily criticised for authorising the National Security Agency to eavesdrop on Americans’ international phone and email communications without first obtaining warrants from courts.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments