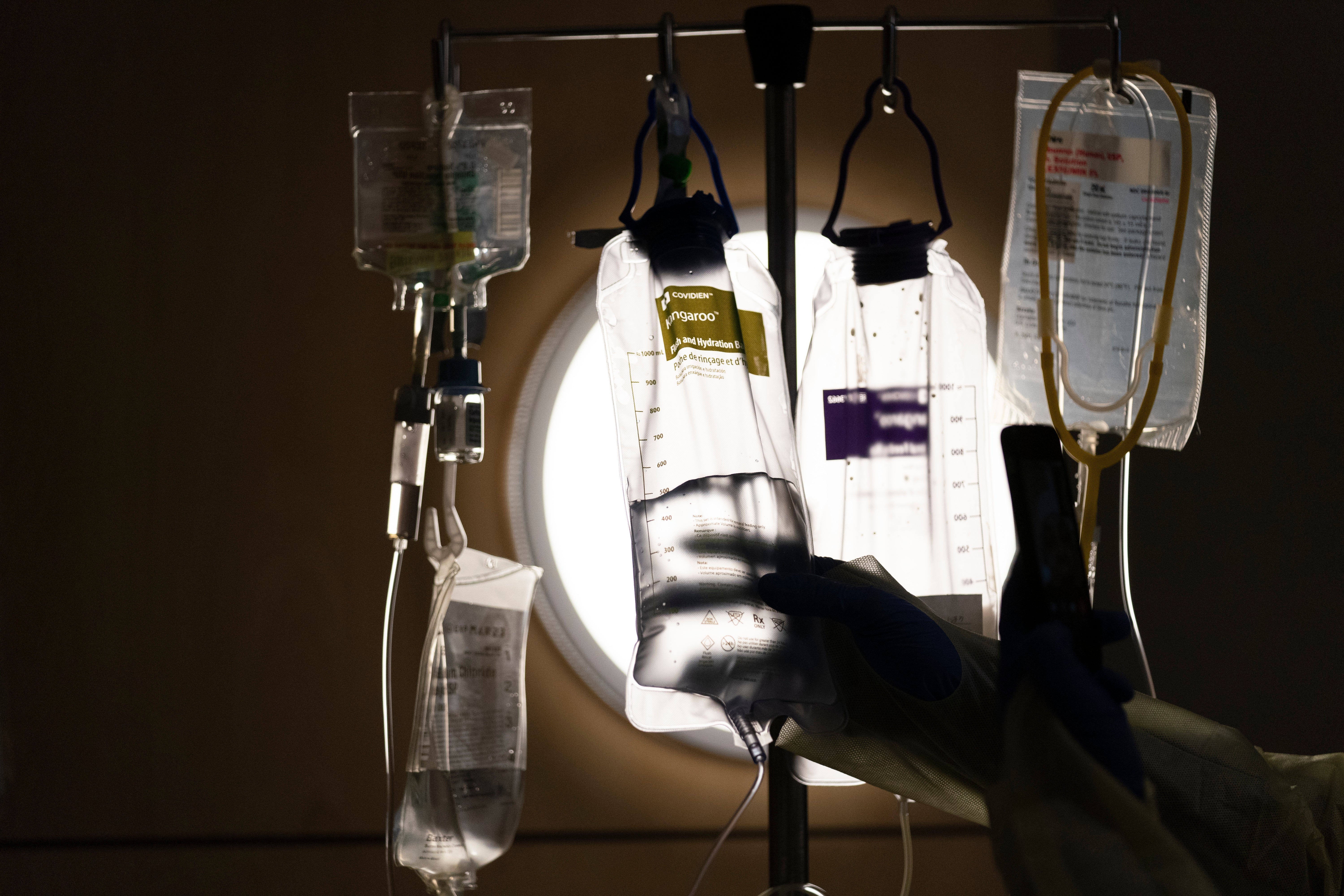

New conservative target: Race as factor in COVID treatment

Some conservatives are taking aim at policies that allow doctors to consider race as a risk factor when allocating scarce COVID-19 treatments, saying the protocols discriminate against white people

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Some conservatives are taking aim at policies that allow doctors to consider race as a risk factor when allocating scarce COVID-19 treatments, saying the protocols discriminate against white people.

The wave of infections brought on by the omicron variant and a shortage of treatments have focused attention on the policies.

Medical experts say the opposition is misleading. Health officials have long said there is a strong case for considering race as one of many risk factors in treatment decisions. And there is no evidence that race alone is being used to decide who gets medicine.

The issue came to the forefront last week after Fox News host Tucker Carlson, former President Donald Trump and Republican Sen. Marco Rubio jumped on the policies. In recent days, conservative law firms have pressured a Missouri-based health care system, Minnesota and Utah to drop their protocols and sued New York state over allocation guidelines or scoring systems that include race as a risk factor.

JP Leider, a senior fellow in the Division of Health Policy and Management at the University of Minnesota who helped develop that state’s allocation criteria, noted that prioritization has been going on for some time because there aren’t enough treatments to go around.

“You have to pick who comes first,” Leider said. “The problem is we have extremely conclusive evidence that (minorities) across the United States are having worse COVID outcomes compared to white folks. ... Sometimes it’s acceptable to consider things like race and ethnicity when making decisions about when resources get allocated at a societal level.”

Since the pandemic began, health care systems and states have been grappling with how to best distribute treatments. The problem has only grown worse as the omicron variant has packed hospitals with COVID-19 patients.

Considerable evidence suggests that COVID-19 has hit certain racial and ethnic groups harder than whites. Research shows that people of color are at a higher risk of severe illness, are more likely to be hospitalized and are dying from COVID-19 at younger ages.

Data also show that minorities have been missing out on treatments. Last week, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention published an analysis of 41 health care systems that found that Black, Asian and Hispanic patients are less likely than whites to receive outpatient antibody treatment.

Omicron has rendered two widely available antibody treatments ineffective, leaving only one, which is in short supply.

The Food and Drug Administration has given health care providers guidance on when that treatment, sotrovimab, should be used, including a list of medical conditions that put patients at high risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19. The FDA’s guidance says other factors such as race or ethnicity might also put patients at higher risk.

The CDC's list of high-risk underlying conditions notes that age is the strongest risk factor for severe disease and lists more than a dozen medical conditions. It also suggests that doctors and nurses “carefully consider potential additional risks of COVID-19 illness for patients who are members of certain racial and ethnic minority groups.”

State guidelines generally recommend that doctors give priority for the drugs to those at the highest risk, including cancer patients, transplant recipients and people who have lung disease or are pregnant. Some states, including Wisconsin, have implemented policies that bar race as a factor, but others have allowed it.

St. Louis-based SSM Health, which serves patients in Illinois, Missouri, Oklahoma and Wisconsin, required patients to score 20 points on a risk calculator to qualify for COVID-19 antibody treatment. Non-whites automatically got seven points.

State health officials in Utah adopted a similar risk calculator that grants people two points if they’re not white. Minnesota’s health department guidelines automatically assigned two points to minorities. Four points was enough to qualify for treatment.

New York state health officials’ guidelines authorize antiviral treatments if patients meet five criteria. One is having “a medical condition or other factors that increase their risk for severe illness.” One of those factors is being a minority, according to the guidelines.

The protocols have become a talking point for Republicans after The Wall Street Journal ran an op-ed by political commentators John Judis and Ruy Teixeira this month complaining that New York’s policy is unfair, unjustified and possibly illegal. Carlson jumped on Utah's and Minnesota’s policies last week, saying “you win if you’re not white.”

Alvin Tillery, a political scientist at Northwestern University, called the issue a winning political strategy for Trump and Republicans looking to motivate their predominantly white base ahead of midterm elections in November. He said conservatives are twisting the narrative, noting that race is only one of a multitude of factors in every allocation policy.

“It does gin up their people, gives them a chance in elections,” Tillery said.

After the Wisconsin Institute for Law and Liberty, a conservative law firm based in Madison sent a letter to SSM Health on Friday demanding that it drop race from its risk calculator, SSM responded that it already did so last year as health experts' understanding of COVID-19 evolved.

“While early versions of risk calculators across the nation appropriately included race and gender criteria based on initial outcomes, SSM Health has continued to evaluate and update our protocols weekly to reflect the most up-to-date clinical evidence available,” the company said in a statement. “As a result, race and gender criteria are no longer utilized.”

America First Legal, a conservative-leaning law firm based in Washington, D.C., filed a federal lawsuit Sunday against New York demanding that the state remove race from its allocation criteria. The same firm warned Minnesota and Utah last week that they should drop race from their preference factors or face lawsuits.

Erin Silk, a spokeswoman for New York state's health department, declined to comment on the lawsuit. She said the state’s guidance is based on CDC guidelines and that race is one of many factors that doctors should consider when deciding who gets treatment. She stressed that doctors should consider a patient’s total medical history and that no one is refused treatment because of race or any other demographic qualifier.

Minnesota health officials dropped race from the state's criteria a day or two before receiving America Legal First’s demands, Leider said. They said in a statement that they’re committed to serving all Minnesotans equitably and are constantly reviewing their policies. The statement did not mention the letter from America Legal First. Leider said the state is now picking treatment recipients through a lottery.

Utah dropped race and ethnicity from its risk score calculator on Friday, among other changes, citing new federal guidance and the need to make sure classifications comply with federal law. The state's health department said that instead of using those as factors in eligibility for treatments, it would “work with communities of color to improve access to treatments” in other ways.

Leider finds the criticism of the race-inclusive policies disingenuous.

“It’s easy to bring in identity politics and set up choices between really wealthy folks of one type and folks of other types,” he said. “It’s hard to take seriously those kinds of comparisons. They don’t seem very fair to reality.”