Democrats need another miracle in Georgia – can Stacey Abrams deliver?

Abrams narrowly lost the 2018 election to Brian Kemp in a defeat that remains bitterly painful and controversial. Four years later, she hopes to pull off an against-the-odds victory, Andrew Buncombe writes from Atlanta

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

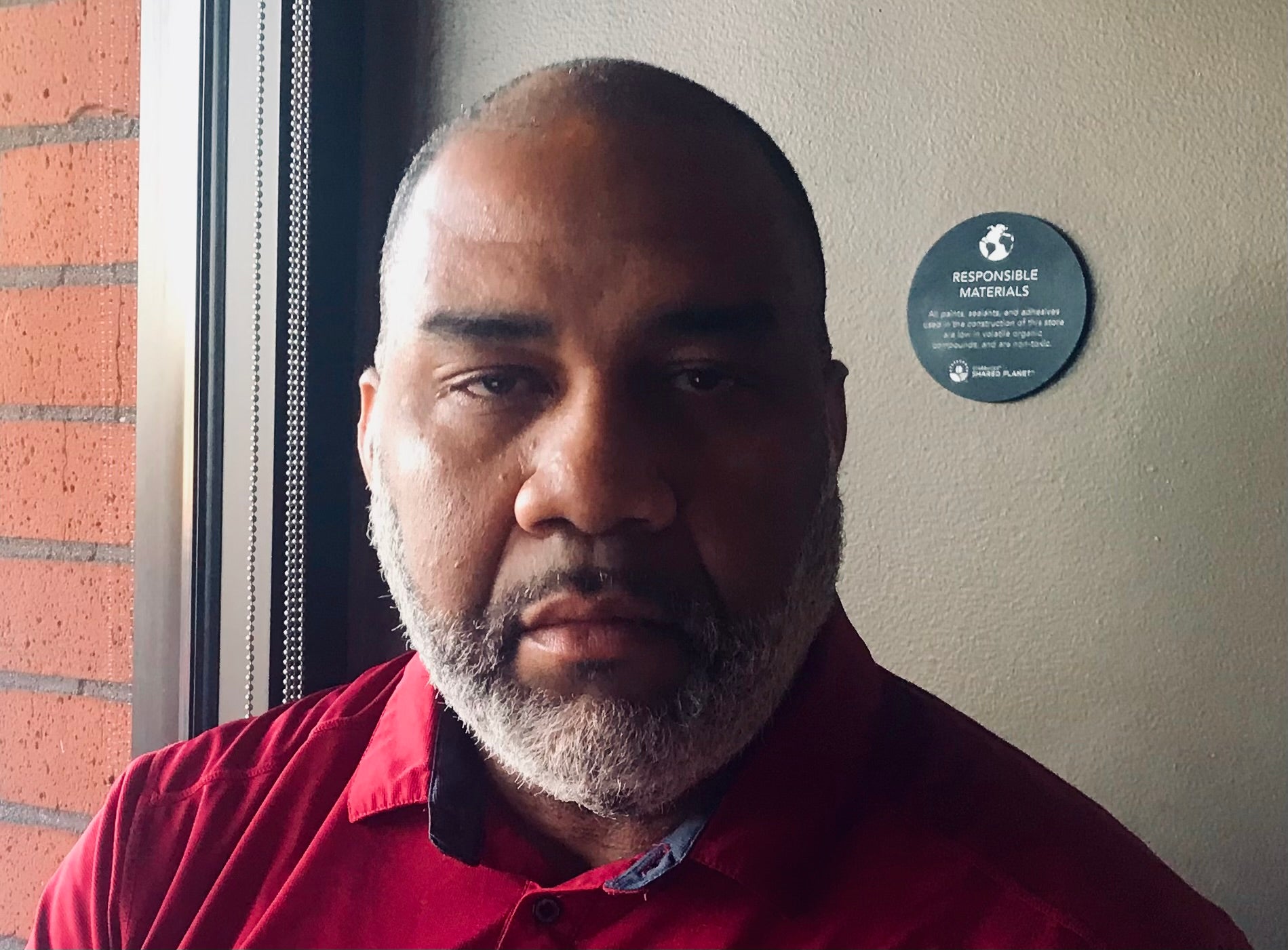

Your support makes all the difference.Delmar Whittington agrees with a lot that Stacey Abrams says.

He attended Atlanta’s historically Black Morehouse College, while his wife went to Spelman, the similarly celebrated women’s university, where Abrams also studied. She was just a couple of years behind them

Like Abrams, Whittington believes the interests of too many people in Georgia – poor and disenfranchised, and often people of colour – have been overlooked for too long.

And like Abrams, he believes the Democratic candidate for governor can pull off an against-the-odds victory, no matter what the polls may say.

“I think there’s chance for her to win, but she has to get out the vote,” he says, sitting in a coffee shop on a chilly Atlanta morning that appears to mark the start of winter. “I do think that people are engaged.”

Whittington, 49, a tech consultant who moved to Georgia more than 20 years ago, is not only planning to vote for Abrams, but encouraging others to do so.

He says he will try to knock on the doors of those who may feel the election has little to offer them, and urging them to register.

Abrams, 48, narrowly lost four years ago to Brian Kemp in a defeat that remains bitterly painful and controversial; she alleged many of her would-be potential supporters were unable to cast a ballot as a result of voter suppression laws he supported in his then position as Georgia’s Secretary of State.

Abrams’ response to that 2018 loss was to commit herself to registering new voters, many of them Black, and telling them that they could make a difference, if only they showed up.

Two years later, in November 2020, Abrams was hailed as nothing less than a hero and credited with registering up to 800,000 new voters, a turn-out that allowed Joe Biden to narrowly win Georgia, the first Democrat to do so since Bill Clinton in 1996.

Biden won by just 11,779 votes, a figure reached at two weeks post-election day, after officials ordered a state-wide audit and deflected demands from Donald Trump to “find” him extra votes.

“We changed not only the trajectory of Georgia, we changed the trajectory of the nation,” Abrams said at the time.

“Because our combined power shows that progress is not only possible, it is inevitable.”

Back then, it was assumed that Abrams would be able to deploy the same strategy to win beat Kemp in a rematch, and in doing so become the state’s first Black governor.

But the polls, as well as interviews with people across the state, suggest it is not going to be that easy.

A lot of people credit Kemp with adopting policies that helped Georgia endure the pandemic, and keep its economy strong.

One recent poll, commissioned by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution gives Kemp a lead of seven points. An average of polls collated by Real Clear Politics, puts the Republican at 7.6 points ahead of Abrams.

Some have said there is more than the governorship itself riding on the outcome of the race.

Abrams, a multi-tasking progressive who was formerly minority leader of the Georgia House of Representatives, as well as a successful novelist, was among those Biden considered as a potential running mate back in the summer of 2020, before choosing Kamala Harris.

If Abrams loses to Kemp a second time, there will be questions not simply about her own future, but also about her tactics of trying to secure victory with the support of part of society that does not always vote, instead of tailoring her message for a more moderate middle ground that needs to be less “persuaded”.

In particular, questions have been asked whether Abrams has failed to communicate adequately with African American men.

Black women are traditionally the most reliable voters for Democratic candidates, but a poll showed her support among Black men a little less than it was in 2018. The polls suggested she was securing less traction than Democratic senator Raphael Warnock, who won a special election in Georgia in 2021 and is seeking election to a full term.

Perhaps understandably, Abrams has snapped at the suggestion she has paid insufficient attention to one part of the electorate, especially given she was credited in large part not just for the victories of Biden and Warnock, but also Jon Ossoff, whose win in another run-off gave Democrats control of the Senate.

Talking to the New York Times, she was asked why she had “struggled” in that respect.

“We have not struggled. Your story was wrong. And I’m going to say that very directly because in 2018, I had the very same conversations,” Abrams said firmly. “In 2018, I was castigated in Georgia because I was having conversations with communities that were marginalised and disadvantaged. And in 2022, I did the exact same thing because I know that these are persuasion voters.”

She added: “But I’m not persuading them not to vote for a Republican. I am persuading them that voting matters and that they can trust a political leadership that they have really never seen deliver for them.”

In an attempt to gauge the mood of voters, The Independent drove to the city of Rome, in northwest Georgia, and the seat of Marjorie Taylor Greene, from Wrightsville, the hometown of Republican Senate candidate and former American Football player Herschel Walker.

There were lots of signs for both Kemp and Abrams.

In the more rural areas, there were more Kemp posters and banners, his name set in white letters against a deep blue background with a red trim.

In the approach to Atlanta, Abrams’s yard signs – her name also written in white on blue background, with a white trim – outnumbered those of Kemp.

It was an imperfect way to poll support, but a useful pointer to their bases of support. In places such as Atlanta, Abrams really needs to win big.

Working up a sweat at a car wash in Milledgeville, a small town about 100 miles southwest of Atlanta, Herman Holl denies the suggestion that African American men will not vote for Abrams.

“I’m a Democrat all the way,” says Holl, 60, himself African American. He says he remembers Walker as a football star, but that he will be voting for Raphael Warnock, the Democratic candidate in the senatorial showdown.

Of Abrams, he says: “I hope she wins this time.”

In the historic city of Forsyth, 60 miles south of Atlanta, African Americans account for 49 per cent of the population, the largest group.

Parts of the city look run down to say the least. The 2020 census suggests 20 per cent of its residents live below the poverty line.

“Stacey Abrams should have won the last election,” says a 41-year-old man who goes by the name Mr Lamar. He points out that in 2018 and this year, Kemp is being supported by the National Rifle Association (NRA).

Critics of Kemp claim that this spring his campaign for re-election received $50,000 from Daniel Defense, a Georgia company that sells and ships controversial AR-15 semi-automatic rifles, including the one used in the attack on the school in Uvalde, Texas.

It emerged that $25,000 of that money was donated less than a month Kemp signed into law new legislation that weakened gun regulations.

Paulette Davis, 62, has a sign in her front garden proclaiming her support for “Miss Abrams”.

“I voted for her four years ago,” she says, adding she will also be supporting Warnock, and that she watched some of the debate between him and Herschel Walker.

She says the economy is bad, and that people are having to pay extra for gasoline for their cars. Despite that, she thinks “if you believe, it can happen”.

Of Abrams, she adds: “I hope that this year will be different.”

But will it?

For every hopeful champion such as Davis, there is someone such as Jerry Ward, a 60-year-old lawyer who is having coffee in the same Atlanta Starbucks as Delmar Whittington, the Abrams supporter.

Ward and Whittington are sitting at nearby high-stool tables, drinking their coffee and tapping away at their laptops. While Whittington is backing Democrats for each race, Ward is voting Republican.

He says the economy is the most important issue to him and says Kemp has performed well.

“I don’t like Stacey Abrams,” he says of the progressive’s ideas. “I think Kemp has shown he can do the job.”

Another problem for Abrams is that when you speak to Democrats across Georgia, they fear that many independents – and even perhaps some in their own party – will end up voting for Kemp because of the way he stood up to Donald Trump in November 2020 and rebutted his demand help him sway the election.

Some people have been reminded of such episodes by the hearings of the Jan 6 committee, that not only examined the pressure put on Kemp, but the Republican Secretary of State, Brad Raffensperger.

Abrams was asked about this in her interview with the New York Times.

“He didn’t commit treason,” she hit back.

“Every other governor also managed to not commit treason. We are lionising someone because he did what every other governor in American history has done. That’s it.”

Abrams and Kemp have held two debates.

In the first they clashed over Covid and crime, with Kemp accusing her of being soft on crime and not having the support of any state-wide law enforcement organisations

“Mr Kemp, what you are attempting to do is continue the lie that you’ve told so many times, I think you believe it’s the truth,” she said. “I support law enforcement and did so for 11 years, and worked closely with the Sheriffs Association.”

Over the weekend, they sparred again. “This debate’s going to be a lot like the last one,” Kemp said. “Ms Abrams is going to attack my record because she doesn’t want to talk about her own record.”

Clearly sensing the need to make up some ground with Kemp, whose position is helped by being the incumbent, Abrams sought to tie him to the scandals that jolted the campaign of Walker, who has been been accused of having been violent towards an ex-wife and paying for a former girlfriend to have an abortion.

Walker has denied the allegations and it is unclear to what degree the allegations have harmed his chances.

Abrams said Kemp had “defended Herschel Walker, saying that he didn’t want to be involved” in his personal life. She added: “But he doesn’t mind being involved in the personal lives and the personal medical choices of the women in Georgia. What’s the difference?”

If she wins, Abrams would not only be Georgia’s first Black female governor, but the first in the nation. (Georgia has only had men fill the job, all of them white. Indeed, there have only been four Black governors in America’s history.)

As such, when people of colour in Georgia talk about the scale of the challenge Abrams is facing it is very much based on their own lived experience.

In the city of Forsyth, that traces its founding to 1823, Catanaja Jones, 52, a social worker, is among those tying to educate people about Abrams, and the election.

She says the state needs someone at its helm who helps “all the people”.

“We all bleed the same colour – red,” she says.

Does she think Abrams can pull off this feat against the odds?

“Of course there is a possibility,” she says. “If we were united, we would be better.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments