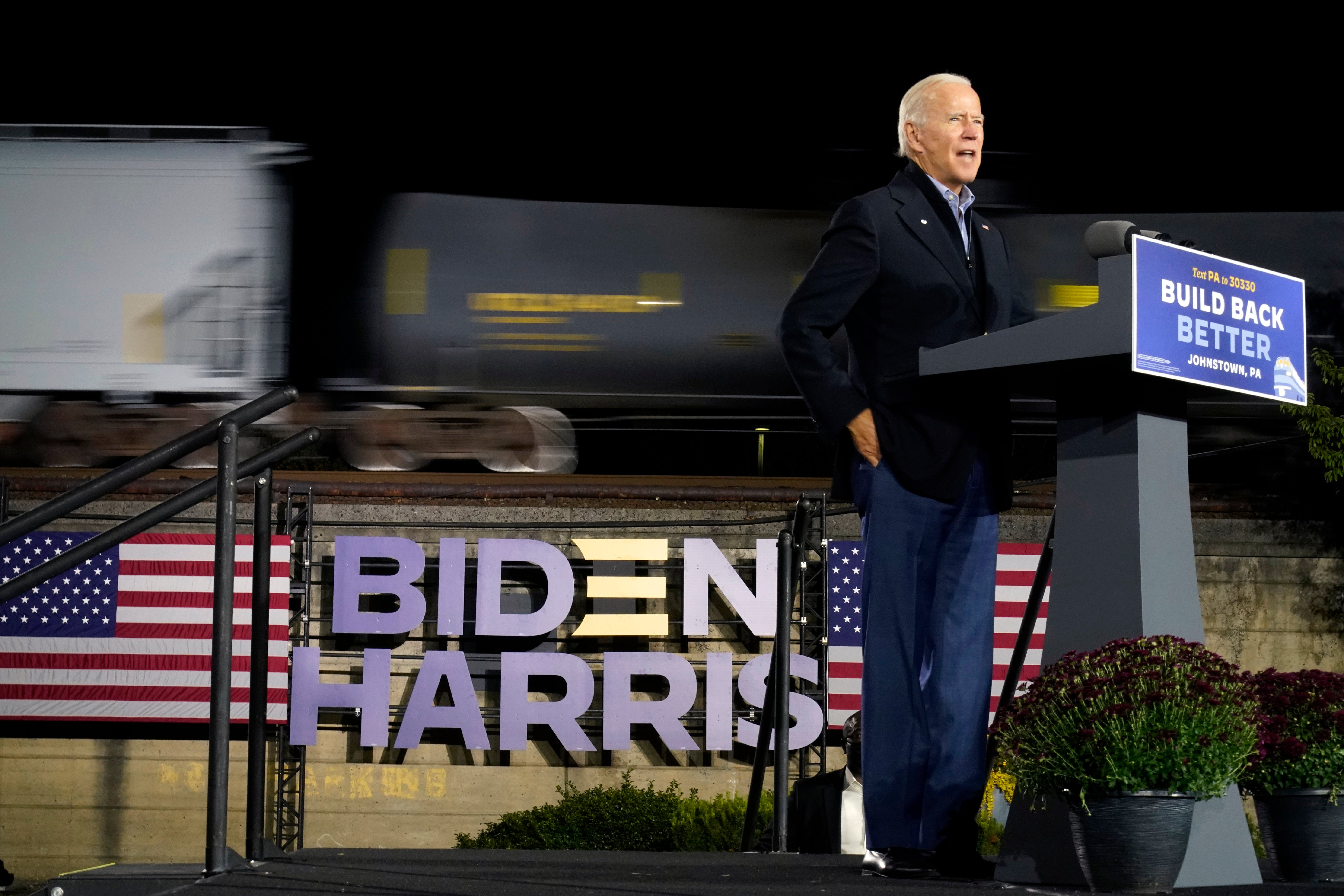

Biden's tight spot: a union backer out to avert rail strike

President Joe Biden believes unions built the middle class

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.President Joe Biden believes unions built the middle class. He also knows a rail worker strike could damage the economy ahead of midterm elections.

That left him in the awkward position Wednesday of espousing the virtues of unionization in Detroit, a stalwart of the labor movement, while members of his administration went all-out to keep talks going in Washington between the railroads and unionized workers in hopes of averting a shutdown.

United Auto Workers Local 598 member Ryan Buchalski introduced Biden at the Detroit auto show as “the most union- and labor-friendly president in American history” and someone who was “kickin’ ass for the working class.” Buchalski harked back to the pivotal sitdown strikes by autoworkers in the 1930s.

In the speech that followed, Biden recognized that he wouldn’t be in the White House without the support of unions such as the UAW and the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, saying autoworkers “brung me to the dance.”

But back in Washington, officials in his administration were in tense negotiations to prevent a strike — one of the most powerful sources of leverage that unions have to bring about change and improve working conditions.

A stoppage could begin as early as Friday if both sides can't agree on a deal. Out of the 12 unions involved, the International Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers District 19 rejected a deal but agreed to prolong talks through Sept. 29. That bought a bit of time, but not necessarily any more certainty as a stoppage is still possible that could halt shipments of food and fuel at a cost of $2 billion a day.

Far more is at stake than sick leave and salary bumps for 115,000 unionized railroad workers. The ramifications could extend to control of Congress and to the shipping network that keeps factories rolling, stocks the shelves of stores and stitches the U.S. together as an economic power.

That’s why White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, speaking aboard Air Force One as it jetted to Detroit, said a rail worker strike was “an unacceptable outcome for our economy and the American people.” The rail lines and their workers’ representatives “need to stay at the table, bargain in good faith to resolve outstanding issues, and come to an agreement,” she said.

Biden faces the same kind of predicament faced by Theodore Roosevelt in 1902 with coal and Harry Truman in 1952 with steel — how do you balance the needs of labor and business in doing what's best for the nation? Railways were so important during World War I that Woodrow Wilson temporarily nationalized the industry to keep goods flowing and prevent strikes.

Inside the White House, aides don't see a contradiction between Biden's devotion to unions and his desire to avoid a strike. Union activism has surged under Biden, as seen in a 56% increase in petitions for union representation with the National Labor Relations Board so far this fiscal year.

One person familiar with the situation, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss White House deliberations on the matter, said Biden's mindset in approaching the debate was that he's the president of the entire country, not just for organized labor.

With the economy still recovering from the supply chain disruptions of the pandemic, the president's goal is to keep all parties at the table until a deal is finalized. The person said the White House saw a commitment to keep negotiating in good faith as the best way to avoid a shutdown while exercising the principles of collective bargaining that Biden holds dear.

Biden also knows a stoppage could worsen the dynamics that have contributed to soaring inflation and created a political headache for the party in power.

Eddie Vale, a Democratic political consultant and former AFL-CIO communications aide, said the White House is pursuing the correct approach at a perilous moment.

“No one wants a railroad strike, not the companies, not the workers, not the White House," he said. "No one wants it this close to the election.”

Vale added that the sticking point in the talks was about "respect basically — sick leave and bereavement leave,” issues Biden has supported in speeches and with his policy proposals.

Jake Rosenfeld, a sociologist at Washington University in St. Louis, noted that the sticking points in the talks involve “more schedule predictability, and the ability to take time off to deal with routine medical procedures as well as emergencies."

On a policy front, the administration generally supports these demands, and that lessens their “willingness to really play hardball with the unions who have yet to settle,” said Rosenfeld, who wrote the book “What Unions No Longer Do.”

Sensing political opportunity, Senate Republicans moved Wednesday to pass a law to impose contract terms on the unions and railroad companies to avoid a shutdown. Democrats, who control both chambers in Congress, blocked it.

“If a strike occurs and paralyzes food, fertilizer and energy shipments nationwide, it will be because Democrats blocked this bill,” said Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky.

The economic impact of a potential strike was not lost on members of the Business Roundtable, a Washington-based group that represents CEOs. It issued its quarterly outlook for the economy Wednesday.

“We’ve been experiencing a lot of headwinds from supply chain problems since the pandemic started and those problems would be geometrically magnified,” Josh Bolten, the group's CEO, told reporters. “There are manufacturing plants around the country that likely have to shut down. ... There are critical products to keep our water clean.”

The roundtable also had a meeting of its board of directors Wednesday. But Bolten said Lance Fritz, chair of the board’s international committee and the CEO of Union Pacific railroad, would miss it “because he’s working hard trying to bring the strike to a resolution.”

Back at the Labor Department, negotiators ordered Italian food as talks dragged into Wednesday night.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.