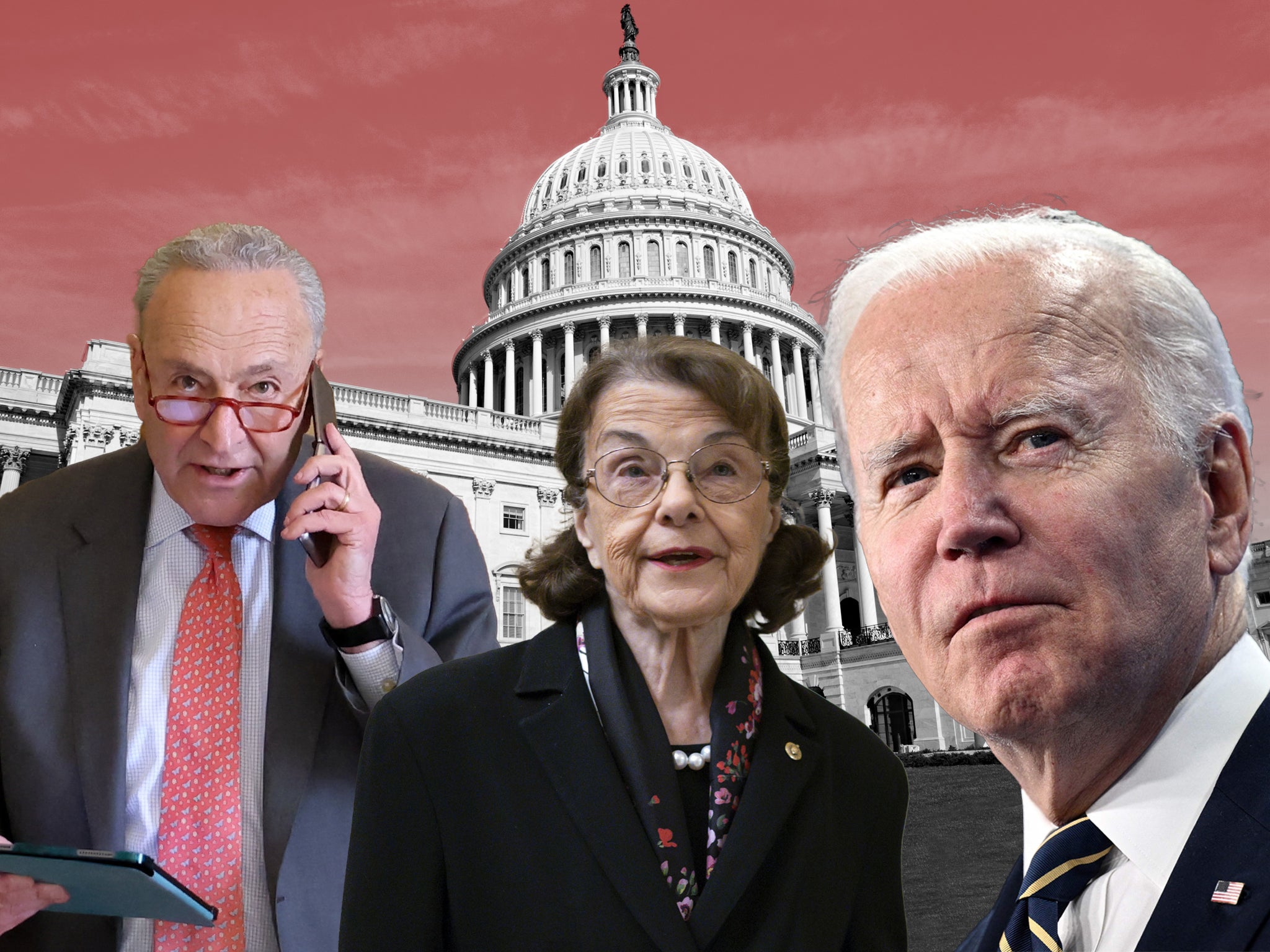

The danger of America’s ageing politicians

As the occupants of the White House and Congress grow older, how will generational conflicts define the future of American politics? Josh Marcus reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Late last month, as Washington’s political and media elite gathered at the Hilton hotel for the White House Correspondents’ Dinner, Joe Biden, 80, couldn’t gloss over a fact that’s increasingly colouring his political future: He’s just an exceptionally old person to be president.

In fact, he’s the oldest person to ever hold the White House.

“I believe in the First Amendment, not just because my good friend Jimmy Madison wrote it,” the president began in his remarks, before good-naturedly taking The New York Times to task for stories about his age.

“You call me old? I call it being seasoned,” he said. “You say I’m ancient? I say I’m wise. You say I’m over the hill? Don Lemon would say that’s a man in his prime.”

The reference was a telling one. Mr Lemon, who was ousted from CNN last month, caused a minor media scandal when he commented about women of a certain age being past their “prime”. This remark was itself a reaction to former South Carolina governor and current presidential contender Nikki Haley calling, somewhat scandalously, for mental competency tests for politicians over age 75.

Generational conflict is nothing new in American politics, but age has played an especially prominent role in Washington in recent months, impacting everything from leadership battles in Congress to the future of the presidency, raising questions about fairness, gender, and the vitality America’s very institutions themselves, which have scarcely ever been filled with more senior citizens.

Mr Biden may have been in a laughing mood at the Correspondents’ Dinner, but that may have just been him putting on a smiling face for the cameras.

His pollsters are surely worried about recent data, such as a March poll finding 68 per cent of registered voters thought he was too old for another term, or an April poll finding that 70 per cent of adults said Mr Biden shouldn’t run again, with the roughly same percentage saying age was a factor in that decision. The age-related worries are just the tip of the iceberg though. Overall, there’s a marked lack of enthusiasm for Mr Biden, with 57 per cent of respondents in a recent poll suggesting the Democrats should nominate someone else in 2024. If these doubts were vanquished, and Mr Biden did win again, he would be 86 by the end of his second term.

If Mr Biden was re-elected, it would further cement the dominance baby boomers have exerted over national politics in recent decades, according to Kevin Munger, assistant professor of political science and social data analytics at Pennsylvania State University, author of Generation Gap: Why the Baby Boomers Still Dominate American Politics and Culture.

“We’ve had 28 years of boomer presidency in a row,” he said. “That streak was only ended by Joe Biden, who is technically too old to be a boomer by two years. That is unprecedented for a single generation.”

Age was a political accelerant during the Donald Trump presidency, too.

Prior to Mr Biden, the billionaire, at age 70, was the oldest person ever to become president. Throughout his presidency, Mr Trump’s mental fitness and cognitive health was a political flashpoint, with the former president bragging about his results on mental competency tests, psychologists openly opining about the president’s mental acuity, and former advisers gossiping to the political press that Mr Trump’s mental decline was so serious cabinet officials considered invoking the 25th Amendment and removing him from office.

Of course, Mr Trump, the insult-comic-in-chief, found a way to turn this speculation against his rival, dubbing Joe Biden “Sleepy Joe” throughout the 2020 campaign season.

It’s not just the White House, though, where age has been a concern.

The present Congress contains the second-oldest Senate and third-oldest House in US history. Generationally, the US population fits roughly into four, equal-sized blocks of about 20 to 25 per cent: ages 0 to 18, 19 to 34, 35 to 54, and 55-plus. The composition of Congress, meanwhile, is drastically tipped toward the elder part of that range, with the median House member aged 57.9 and the median senator aged 65.3.

Beyond just being another way the US government doesn’t mirror the wider diversity of the US population, age within Congress can become a political weapon, used by both parties as part of their machinations.

In March, Senator Dianne Feinstein, 89, the oldest US Senator, who has been dogged in her later years with accusations of declining mental faculties, was hospitalised with shingles, and has had to miss large swathes of in-person work in the upper chamber as she recovers.

The following month, she asked to temporarily be replaced on the key Senate Judiciary Committee, which handles the appointment of federal judges, one of the few remaining ways the Democrats can exert lasting influence in a divided Congress.

However, Republicans, knowing that the full Senate must approve committee assignments, have added a major, likely unacceptable demand for the Democrats: they’ve asked that Senator Feinstein must resign the Senate entirely before they consider a replacement.

In a sign of just how scrambled the politics of age are on the Hill, members of both parties have argued such treatment is unfair, but that hasn’t stopped the GOP from changing its tune.

Sen Chuck Grassley, Republican of Iowa, called the demands “very anti-woman” and “very anti-ageing” in an interview with The Independent, while Sen Elizabeth Warren, Democrat of Massachusetts, argued, “The Republicans are saying no, for no reason, other than trying to block the court from going forward in its investigation of the Supreme Court and pass more judges, which is the right of the majority to do.”

The issue has divided the Democratic Party as well.

In April, rising star California congressman Ro Khanna forcibly called for Sen Feinstein to resign.

“We need to put the country ahead of personal loyalty,” he said. “While she has had a lifetime of public service, it is obvious she can no longer fulfil her duties. Not speaking out undermines our credibility as elected representatives of the people.”

Age has also been a clear undercurrent in House leadership battles, where former House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made a point to highlight the comparative youth of the new slate of Democratic leadership, following at times barbed exchanges between her and younger, more progressive parts of the party like representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

“The hour has come for a new generation to lead the Democratic caucus,” she said in November when she stepped aside. “Now we must move boldly into the future, grounded by the principles that have propelled us this far, and open to fresh possibilities for the future.”

All told, according to Professor Munger, the age of America’s most senior politicians – Sen Chuck Schumer is 71, Sen Mitch McConnell is 81 – often means that issues that matter to other generations don’t get top billing, leading both to disaffection and to bigger-picture existential issues, like a lack of serious climate legislation or the impending funding crisis of social security.

“It’s been clear that because of the size of the boomer generation, at a certain point we were either going to have to raise taxes on the workforce or cut the benefits,” he said. “We didn’t do either of those things. Sometime in the 2030s, it’s going to run out. They’re not going to cut benefits to boomers. Instead, younger generations are going to have to fully fund this obvious 30-year shortfall.”

In the case of social security in particular, many of the leaders deciding on the issue are current recipients, while those younger generations who will likely pay more or get less in the future aren’t represented in office. A similar problem arises with climate change: the leaders holding up urgent action on the climate likely will not be alive to see the very worst impacts of their inaction.

“The issues that matter to younger generations don’t get on the agenda at all,” Prof Munger added.

Instituting a parliamentary system, he said, instead of our current winner-take-all model might lead to more representational and ideological diversity, but like major climate or benefit reform, overhauling the US election system doesn’t seem to be a consensus priority at the moment.

And those younger generations in turn don’t participate as much as they fully could at the national level.

In the 2022 midterms, only 23 per cent of eligible young Americans cast a ballot, up from 2014’s woeful 13 per cent, but still well below the participation rate of older generations. The same held true in 2020, the highest turnout election of the 21st century: 76 per cent of those aged between 65 and 74 voted, while only 51.4 per cent of those aged 18 to 24 did.

Some of this demographic dominance is unavoidable, argues Philip Bump, Washington Post columnist and author of The Aftermath: The Last Days of the Baby Boom and the Future of Power in America. The boomers, born in the abundant post-war years between 1946 and 1964, were until very recently the largest generation in US history. During their lifetimes, America cemented its place as a global economic superpower, the voting age was lowered to 18, and the federal government poured millions into creating a new middle class. It’s no surprise then, Mr Bump says, that this generation has a strong hold on power.

“The baby boomers make up a disproportionate share of elected officials, especially at the federal level, simply by virtue of scale,” he told The Independent.

Combine that with the built-in political advantages of incumbency and wealth, and you have a recipe for a political system tilted towards older people.

“Senators are not usually just elected out of the blue,” he added.

Some argue that critcising elected leaders, and the system at large, over age concerns is ageist, and often sexist as well, given the extra scrutiny paid to leaders such as former Speaker Pelosi or Senator Feinstein.

However, according to Amanda Litman, co-founder of Run for Something, an organisation that encourages young people to run for office, this is largely missing the point. Any one elected leader can be an effective and competent advocate regardless of age, she told The Independent, but we must acknowledge that the system at large needs to allow more young people in.

“This isn’t about any one person. This is about a collective problem of Congress not being reflective of the American people,” she said. “We know that in business, and in other governments, things work better when they’re made up of diverse perspectives. All of us would be better served if there were more voices at the table.”

According to Penn State’s Professor Munger, debates about age in politics aren’t new. During Ronald Reagan’s second term, similar conversations about mental fitness and age circulated around the Beltway and the country at large. And, despite the apparent controversy of someone like Nikki Haley calling for age limits, the US already has such policies in other arenas, like age requirements for generals or pilots, or mandatory retirement ages in certain other professions.

What makes these conversations often intractable, though, is that they’re not really ever just a conversation about age or reform, he argues. Both parties are always considering the partisan stakes.

“There’s no way to have that debate except through the lens of immediate political reference,” he said.

Finding some resolution to the generation wars will be urgent, however. There’s a higher per cent of Americans older than 65 than there has ever been in US history, so questions about age, competence and representation aren’t going away any time soon. Neither are big-picture problems like the climate crisis, where urgent action is needed now to prevent impacts that will play out in both a matter of seasons and centuries.

Ms Litman, of Run for Something, is encouraged by recent research her organisation did, which found that more than 130,000 young people around the country wanted to run for office. To her, it showed that for all the inaccessibility of the US political system, younger generations have the same urge to serve as those who came before them.

“We often hear, young people don’t vote. They don’t want to engage,” she said. “That’s not true. You have to ask. You have to open the door to them. When you do, they are ready and eager to run right through it.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments