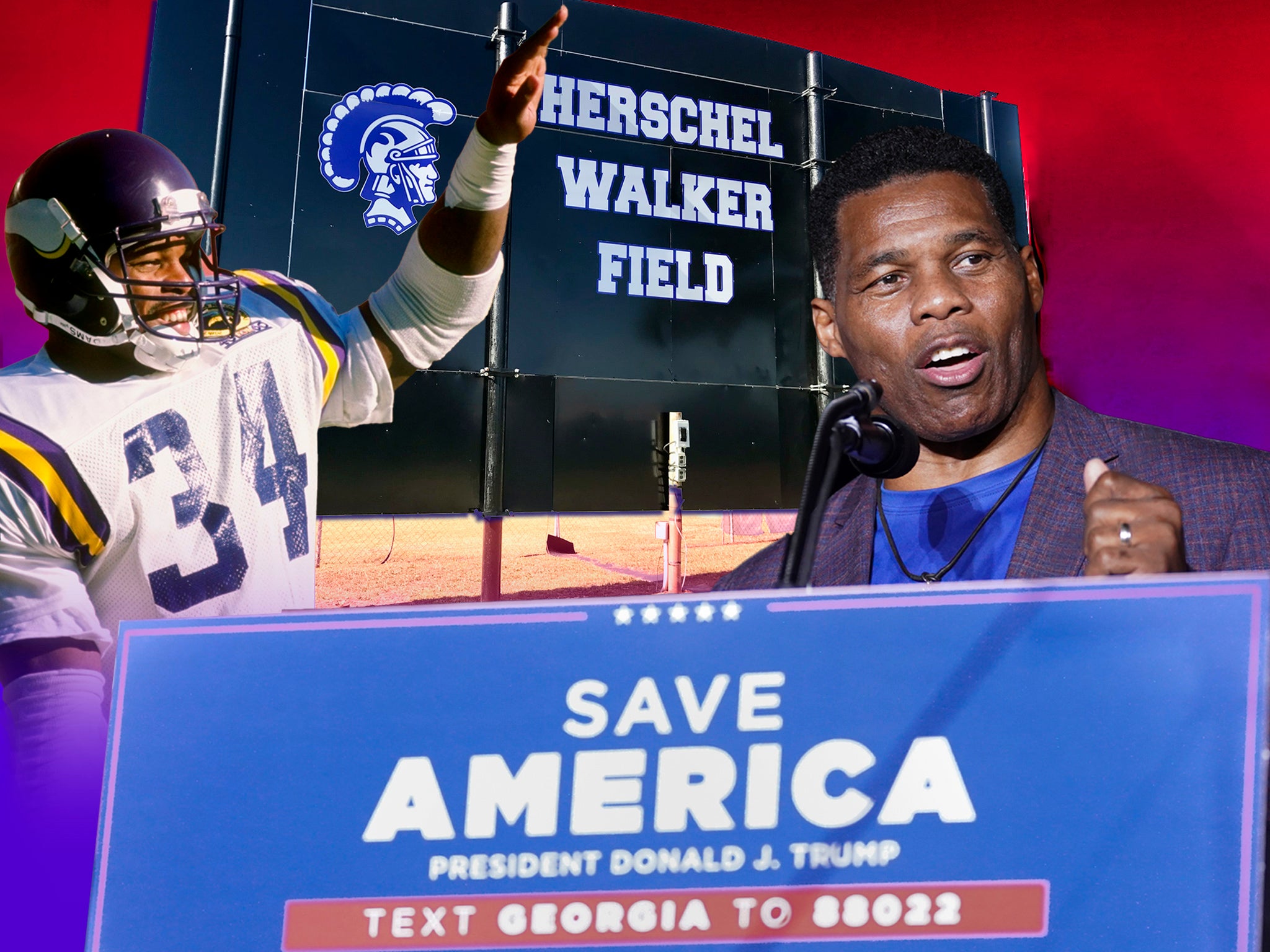

Hero or hypocrite - what do voters in football-mad Georgia really think of Herschel Walker?

The Republican is certainly a celebrity but it’s not clear that will be enough to secure victory, writes Andrew Buncombe in the former football star’s hometown of Wrightsville, Georgia

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.There’s a buzz when The Trojans bound onto the field – zipping with speed and elasticity even if they are half-blinded by the stadium lights.

The Trojans of Johnson County High School are something of a powerhouse in this part of Georgia, winning the first of several state championships all the way back in 1979 with the help of a certain Herschel Walker.

Walker, of course, is not on the team tonight, but there is excitement about 18-year running back Germivey Tucker, who is close to breaking one of the former player’s records set decades ago.

And everyone remembers Walker as the startlingly powerful student athlete who overcame adversity and is now trying to lever his fame and reputation for political office. Several in the crowd say they played against him.

“He is very well known. He was the best,” says 63-year Ricky Todd. “I will be voting for him. I vote Republican.”

Herschel Walker, now aged 60, is hoping there are lots of people in Georgia like Ricky Todd.

One of seven children and who grew up in rural Georgia around the time of the passage of the 1965 Voting Rights Act, Walker has put his personal story at the very centre of his campaign for political office.

If he could defy the odds to become a record-breaking high school athlete, then a star player at the University of Georgia and win an esteemed prize, and complete 15 seasons as a professional, then do not bet against him to win a seat on the US Senate, he says.

“God prepared me for this moment,” he recently told Fox News anchor Sean Hannity.

Yet it is not that simple – far from it. Walker is certainly revered in this part of conservative, football-mad Georgia, for his sporting achievements and for a putting part of the state on the sporting map.

But not all of those admirers think Walker is cut out for political office. When he entered the race last year, there were plenty of voices who questioned his suitability for the job.

As it was, Walker – endorsed by Donald Trump on whose Celebrity Apprentice he had once appeared – easily won this summer’s Republican primary, bettering his nearest challenger, Gary Black, by more than 50 points.

His Democratic rival, Rev Raphael Warnock, elected in January last year, did not appear insurmountable. With Joe Biden’s approval rating at best modest, and inflation seemingly unstoppable in the short term, perhaps Republicans could pick up this seat and help win back control of the upper house of Congress.

There were no doubt some vulnerabilities. Walker’s past included struggles with mental health, and an episode from 2001 when he pulled a gun on his estranged first wife and threatened to kill her.

But Walker had written about this in a 2008 book, Breaking Free: My Life with Dissociative Identity Disorder, when he talked about his mental health struggles and being raised literally on the wrong side of Wrightsville’s railway tracks. He revealed he had been diagnosed with dissociative identity – or split personality disorder – and claimed he did not remember the incident of aggression

If it was a showdown between between two personalties, Warnock could win, former House Speaker and Georgia native Newt Gingrich told Politico this summer.

He added: “But if this is a big race, and it comes down to Warnock’s being part of nine per cent inflation and highest price gas in history, and you can go down the list, then I think Warnock loses.”

But then Walker’s campaign was shaken, with a succession of jolts more firmly felt even than those incurred driving over the disused tracks near his home.

Firstly it was reported by The Daily Beast that Walker – who had publicly berated absentee fathers within the African American community – had a son whom he had never acknowledged, in addition to the son he often talked about.

It was then reported he had two other children, a son and a daughter.

Days later, it was claimed that Walker, a conservative Christian running in a state where abortion had just been all but banned, had paid for a woman to have an abortion, once in 2009, and then a second time in 2011 when she declined to do so and instead gave birth to the child.

Walker rejected claims of trying to hide having four children, saying he wanted to spare them from the spotlight, and he denied the claims about paying for abortions, despite reporters obtaining the receipts for the documents.

One of those calling the sports star a hypocrite was his son Christian Walker.

He tweeted: “Every family member of Herschel Walker asked him not to run for office, because we all knew (some of) his past. Every single one. He decided to give us the middle finger and air out all of his dirty laundry in public, while simultaneously lying about it.”

In a different era – or perhaps most critically at a different stage in the race – all this might have marked the end of Walker’s campaign.

How could a purported Christian, a man running on a “pro-life” platform of opposition to all abortions apparently without exceptions, have acted in such a hypocritical way? Who would ever believe what he said.

Yet, in Georgia it seems that Republican supporters of the sports star have rallied around him, not because of his status as an athletic hero, but plain and simply because he is their candidate, and there is no time to select another.

Polls back up this perception.

One by Quinnipiac, that gave Warnock a lead of around seven points over Walker, has remained unchanged at 52-45. “In the wake of a controversy that’s landed Republican Senate candidate Herschel Walker in the national spotlight, the race for US Senate in Georgia remains essentially unchanged,” says the polling company.

A collation of polls by the website Five Thirty Eight suggests the Democrat has gained three points since the controversy. An average by Real Clear Politics gives a similar lead to Warnock.

Many of those who are most outspoken in their defence of Walker are white Christians who have placed “Walker For Senate” signs in their homes and gardens.

Janibeth Outlaw, a Republican, was sworn in as Wrightsville’s first female mayor two years ago. She says she is hopeful Walker will win.

“I met Herschel Walker several years back. In our very first conversation it was like I was talking to an old friend,” says the 37-year-old.

“Herschel is a great guy, a wonderful person. We’re excited about the possibility of him representing Wrightsville, Georgia, not only for our town but small towns like ours all across the state. Sometimes rural Georgia gets left out a little bit.”

But what do the people of Wrightsville, population 3,600 and located 150 south east of Atlanta, make of the accusations that have been leveled at his campaign and the allegations of hypocrisy?

“I know people are very concerned that some of that was fabricated,” she says. “And I know people are looking at what his policies are now. Most people know that he is pro-life, and they are going to vote based on what he’s saying now.”

Also rooting for Walker is 60-year-old Jeff Powell, another white resident, who said the Democrats had allowed inflation and the cost of gasoline to sky-rocket.

He says he does not believe the allegations being leveled at Walker. “I think he will do a good job.”

Mark and Lisa Clark live close to where Walker grew up on the edge of town.

Clark says they are both conservatives and that he and wife, who went to the city’s high school, though not at the same time as Walker, will vote for him.

He says that on holidays such as July 4, Walker and his family take part in local parades. “I plan to vote Republican because we’re a conservative household.”

It was at Wrightsville’s Johnson County High School that Walker first turned heads with his powerful performances as a student athlete.

He ran track, and his powerful presence made him a useful member of the basketball team.

Yet it was as part of the Trojans American football team from 1976 to 1979 that he began to cement himself in sporting lore. In his senior year, he rushed for a still unbroken record of 3,167 yards, and helped The Trojans win their first state championships.

The stadium where he performed such feats is now named Herschel Walker Field, and in 2017 the road that leads from outside the school to his family home was named Herschel Walker Drive.

While people are happy enough to stop and chat about Wrightsville’s association with the player, there are few other fixed markers of his association with the community. Indeed, that is something frequently raised as a criticism of the former star – that has he never gifted a sports centre or other sort of facility to the place he grew up.

“I will not be voting for Herschel Walker. There have been too many lies,” says 69-year-old Vivian Lee, leaving a grocery store with his brother. “He should not become a politician.”

Walker’s camapign did not respond to questions from The Independent. Yet the criticisms are set against a backdrop of genuine struggle in Johnson County, as in many other parts of rural Georgia and beyond.

Data from the 2020 census suggests the county, which is 60 per cent white, and 34 per cent Black, has an average individual income of around $21,000.

Around 35 per cent of children under the age of 18 are said to live in poverty, along with 14 per cent of senior citizens.

In a Dollar General budget store, customer Stepphon Smith says: “Herschel Walker has done nothing good for us.”

An assistant, Whitney Bell, says she also went to Johnson County High School. Walker was still famous, she says, but “people are not going to vote for him because he has done nothing for his home town”.

Another critic, a 69-year-old woman who did not want to give her name, says: “He’s disowned his home. He has done nothing for it”.

It is hard to exaggerate the level of passion and enthusiasm across large swathes of rural America for non-professional American Football.

It is true there is also love for college football – as well, of course for the highly-paid professionals of the NFL of which Walker was one for 15 years – and every city has its own devotees, usually alumni who spend the rest of their post-student lives maintaining loyalty to those teams.

But it perhaps at high schools in countless unremarkable small towns and cities, where support for the sport can feel most pure and unadulterated.

If you have watched movies such as Friday Night Lights or Remember the Titans, or the spin-off television series they led to, then the drama and passion they contain feels pretty close to real life in terms of the utter centrality of the sports teams to the broader life of the community.

In towns across places such as North Carolina, or Texas, things come to a halt on Friday nights, when hundreds of people gather to watch their high school team.

And it is not just the players they come to see.

They come to watch the highly-drilled cheerleading teams, and school bands that play and blast and blow. There are hot dogs and cheese fries and sodas.

There are lottery tickets to raise money to buy new equipment.

There are photographs and paintings of the players and the staff and sometimes their parents, captured in a moment of seemingly carefree youth, a moment of intensity and attention that will perhaps seldom be repeated in their lives.

Wrightsville, Georgia, is one of those places.

On a recent autumnal Friday, on a day that temperature had started to drop, The Independent drove 50 miles to watch The Trojans play away against the Panthers of Glassock County High School, located in the town of Gordon .

“You’re lucky,” says an official. “Last week we were away, and it was two hours drive each way.”

There is a fizz of expectation in the air. Among the white-jerseyed Trojans is Germivey Tucker, an 18-year running back who is less than 1,000 yards from breaking Walker’s record.

[Tucker will knock off another 246 yards tonight, and be named Offensive Player of the Game in the 47-7 victory over the Panthers.]

For his professional career, Walker wore the No 34 shirt, but at The Trojans he wore 43. Tucker wears 3.

Johnson County coach Don Norton says it is impossible and unfair to make a comparison between Walker and Tucker.

Asked whether he thinks Tucker can beat Walker’s record, he says the team would like him to “break the record”.

“When they wrote the team’s goals down, that was one of [them],” he says.

There are several hundred gathered to watch the game and everyone appears to know Herschel Walker.

Some say they played against him, more than 40 years ago.

Gary Walker is watching his 15-year-old son play for Glassock. He played against Walker at basketball.

Despite that, the retired auto-mechanic says he is backing Democrat Raphael Warnock when it comes to selecting a senator. “Herschel has too much in his past,” he says

On the away team’s bleachers, Anthony Connolly is watching his son play too.

He says he also played against Walker when he was a student at Wilkinson County, before they moved to Wrightsville. He says Walker had the speed and size to “roll you over”.

“He was very good,” says Connelly, who says he is voting for Walker in the upcoming election.

Does he think he can win? “Yes, I think he has a good chance”

Geneva Hicks, who has travelled from Wrightsville to support the team, says she too is backing Walker.

Hicks is 73 and drives school buses. She says she knows he has no experience in elected office. But she agrees with his conservative stance on various positions.

“I think he can surround himself with good people who can help him” she says.

Did she ever see Walker play in person?

Just once, she replies. “He was good.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments