‘Who wants to tell him what happened?’: Republican mocked for saying Socrates would be ‘canceled’ today

‘If Socrates was out philosophising in American society today, he would be canceled real quick’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Florida Republican state Representative Anthony Sabatini waded into the online fray around “cancel culture” with a nod to the ancient philosopher whom he calls his hero.

“If Socrates was out philosophising in American society today, he would be canceled real quick,” the attorney and Republican lawmaker tweeted late Thursday.

The replies and quote-tweets came in the thousands, pointing out that the famous Greek “gadfly” faced what some might call the ultimate cancellation - execution.

“Socrates was literally forced to drink hemlock.”

“Who wants to tell him what happened to Socrates?”

“If I saw this in a student’s essay, I would immediately know they didn’t do the reading,” one person said.

Mr Sabatini, who majored in philosophy and history in college, says he was well aware of how Socrates was executed for corrupting the youth and was trying to make a point - “5th century BC, challenging political correctness got you killed; today it gets you canceled,” as he put it in Twitter messages to The Washington Post.

The controversial conservative, who is now running for Congress against Republican incumbent Representative Daniel Webster, also said that he was demonstrating “Socratic irony” - defined by Oxford Languages as “a pose of ignorance assumed in order to entice others into making statements that can then be challenged.”

“[By] not being VERY explicit for sophist Twitter, [its] automatic response and conventional assumption that a Republican wouldn’t know . . . ends up displaying sophist Twitter’s own ignorance about cancel culture as the societal punishment that Socrates would endure,” Mr Sabatini told The Post.

But Twitter was already abuzz with derision - and discussion about the ways in which Socrates did or did not reflect the politically polarizing concept of being “canceled” for views deemed unacceptable. It fed into a long-running divide: Some, like Mr Sabatini, see an intolerant society where blowback for unpopular opinions can amount to persecution. Others see “cancel culture” as an exaggerated and nebulous charge deployed against legitimate criticism.

“Socrates is actually a great example of ‘cancellation’ as it is often meant, in that he could have easily avoided punishment by taking Crito’s ship away from Athens but instead decided to stick around so he could be martyred and get attention,” tweeted Quinta Jurecic, an editor with legal and national security blog Lawfare.

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy describes Socrates as a towering but mysterious figure who lived from 469 to 399 BC and who profoundly shaped philosophy even though he left behind no writings. Historians have pieced his life together through disciples and a playwright, though they acknowledge these accounts may be flawed.

He stuck out - traveling “barefoot and unwashed, carrying a stick and looking arrogant,” according to the Stanford Encyclopedia. As Plato wrote in “Apology,” Athens would soon recognize Socrates as an intellectual titan who challenged his disciples to question the credibility of men believed to be of wisdom and virtue. In “The Clouds,” playwright Aristophanes depicts the philosopher in the comic play as teaching Pheidippides how to build up arguments that justify him striking and assaulting his father.

Aristophanes noted how many in Athens connected Socrates to the Sophists, “a set of charlatans that appeared in Greece in the fifth century BC, and earned ample livelihood by imposing on public credulity,” according to G.B. Kerferd’s 2009 book “The Sophistic Movement.” Though Socrates denied a connection to Sophism, the supposed link stuck among detractors in Athens who saw Sophists as poisoning the minds of disrespectful youth.

“Professing to teach virtue, they really taught the art of fallacious discourse, and meanwhile propagated immoral practical doctrines,” Mr Kerford wrote of Sophists.

Plato documented how the Socratic method, which aims to promote critical thinking through questions, would be imitated by the impressionable youth of Athens.

His sweeping influence, as well as Socrates’s views on politics and religion - namely that gods should be good or they shouldn’t be gods at all - triggered a trial in 399 BC, as the philosopher was charged with moral corruption of Athenian youth and impiety.

Meletus, who brought Socrates to trial when the philosopher was about 70, pointed to treasonous actions from two of his students, Alcibiades and Critias, who “betrayed Athens and helped Sparta during one of the most devastating wars in the region’s recent memory,” according to Ancient World magazine. To this, Socrates snapped at Meletus, Plato recalled, saying, “[Meletus] cannot harm me, for I do not think it is permitted for the better man to be harmed by the worse.”

Socrates went on to say that his life of questioning did him much good.

“To put it bluntly, I’ve been assigned to this city as if to a large horse which is inclined to be lazy and is in need of some great stinging fly and all day long I’ll never cease to settle here, there, everywhere, rousing and reproving every one of you,” Socrates said, according to “Apology.”

His remarks, however, were in front of a jury that had already determined his fate. He was found guilty of corruption of the youth in Athens and impiety, namely “failing to acknowledge the gods that the city acknowledges” and “introducing new deities.” He was sentenced to death, ordered to take a drink poisoned with hemlock, a highly toxic plant.

This was what getting canceled looked like for Socrates.

Citizens expected Socrates to flee Athens before he had to drink the hemlock, but he refused to run from his legal responsibility, leaning on his teachings of civil obedience to the law.

“All of philosophy is training for death,” he said, according to Plato’s “Phaedo.”

As detailed in “Phaedo,” Socrates, who chose to cover his face, was instructed to walk around after drinking the poison until his legs grew numb. Slowly but surely, the numbness inched up his body and into his heart.

Before his Socrates tweet, Mr Sabatini has been a constant presence in the headlines since he began serving in the Florida House in 2018. State Democrats called on him to resign in 2019 after a photo of him wearing blackface in high school resurfaced - an image the lawmaker claimed was part of a “silly high school prank.” Months later, Sabatini seemingly showed his support for an attack on an Orlando Sentinel reporter. In reply to a video of a Trump supporter who smacked a journalist’s phone and was later arrested, Mr Sabatini simply tweeted, “MAGA.”

Hours before President Donald Trump left office, Mr Sabatini pushed a proposal to rename US Route 27 after Mr Trump. Democrats responded that “not even a bench” should “ever bear the name of this traitor” in the days following the failed insurrection at the Capitol.

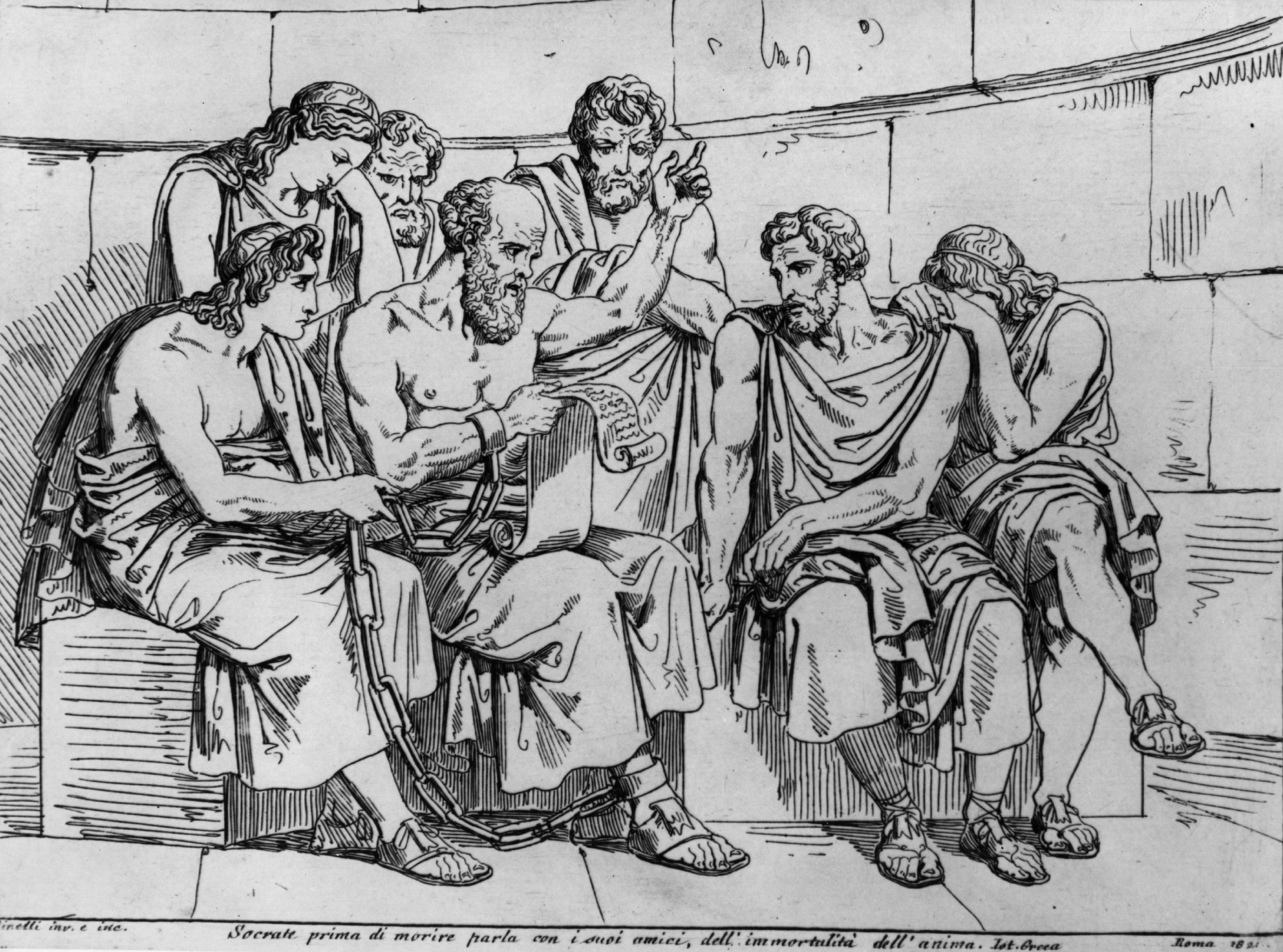

While Mr Sabatini tweeted Friday that he’d been misconstrued, that didn’t stop online critics from having some fun reinterpreting “The Death of Socrates,” the legendary 1787 oil canvas work from French painter Jacques-Louis David. Some even renamed it “The Cancellation of Socrates.”

Max Kennerly, a Philadelphia attorney, even offered a new caption for the canvas that could have fallen in line with Mr Sabatini’s tweet: “Pictured: Socrates enjoying a glass of wine, telling his students, ‘Nobody will ever cancel me!’”

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments