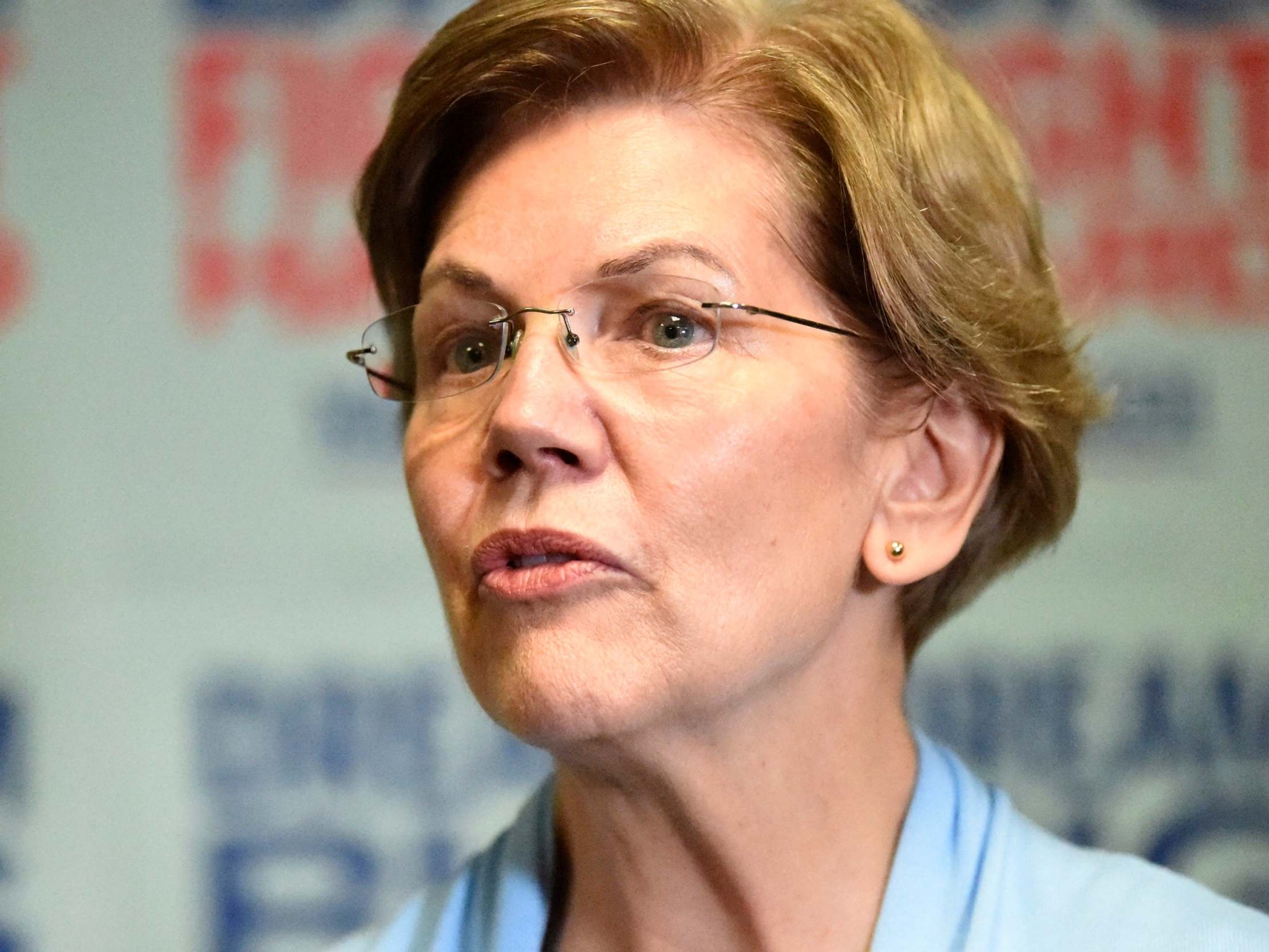

Elizabeth Warren helped company to avoid clearing up toxic waste, document reveals

Democratic hopeful's past work conflicts with her later green credentials

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The memo from then-professor Elizabeth Warren was written on Harvard University law school letterhead, a symbol of gravitas for a scholar renowned as a champion for consumers victimised by predatory banks and other big businesses.

But on this occasion, Ms Warren was not arguing on behalf of vulnerable families, nor was she offering the sort of stinging rebuke of corporate greed that would later define her political career. Rather, Ms Warren was representing a large development company that was trying to avoid having to clean up a toxic waste site.

The memo, which Ms Warren wrote in 1996, used legalistic and often dense language to argue that businesses faced the “risk of the unknown” from a growing threat of lawsuits, and that defended the company's right to “maximise its returns to its unpaid creditors and to survive as an employer.”

“Environmental claims, product liability claims, and mass tort claims, for which we have currently only seen the tip of the iceberg, are multiplying against American businesses,” wrote Ms Warren, who, according to her campaign, was arguing that a different company should bear the cleanup costs.

The eight-page memo, which has not previously been reported, offers a rare glimpse of Warren in action during her past work as a corporate consultant - one whose arguments were at times out of step with the liberal presidential campaign she is running today.

Ms Warren's compensation in the 1996 case was included in a summary released by her campaign late on Sunday night showing that she had been paid about $2m (£1.5m) as a legal consultant during her time as a professor, most of it between 1995 and 2009.

But Ms Warren, who has released 11 years of tax returns, has not disclosed her tax records from most of that time period. And her campaign has provided few details about her private legal business beyond short descriptions released in May of cases she worked on and the Sunday night disclosure, which came amid a growing feud over transparency between now-senator Warren and rival Pete Buttigieg.

Mr Buttigieg, who has accused Ms Warren of not being fully up front about her legal work, on Monday responded to criticisms from Ms Warren about his own secrecy - announcing he had secured permission from the McKinsey & Co consulting firm to disclose information about his time there and saying he would reveal names of major donors collecting checks for his campaign.

Ms Warren's private legal work spanned a diverse portfolio - arguing motions in court, consulting behind the scenes, and filing briefs. Though most of the work was paid, she occasionally provided her services for free, including to help seniors protect retirement accounts and guard against asset seizures.

Among the multiple corporations that hired Ms Warren was Dow Chemical, which spent years trying to ward off liability after a subsidiary company's silicone breast implants began to rupture. She also worked for LTV Steel, a firm that battled with the labour movement as it tried to avoid paying millions of dollars for retired coal miners' health care.

The 1996 case, in which she represented a real estate development company called CMC Heartland fighting in court to avoid having to pay to clean up a polluted old rail yard along the Puget Sound in Washington state, stands out because her memo offers a road map for how she made her arguments.

Warren was paid about $21,000 (£16,000) for the work, according to the data released on Sunday by her campaign.

CMC Heartland Partners was trying to avoid a newly enacted Washington state law that could put it on the hook for about $4m (£3m) of the cleanup costs, according to local news reports. The company, which had acquired the land through a bankruptcy proceeding, argued that the legal manoeuvre should have shielded it from responsibility.

Ms Warren's memo was sent to the US Justice Department in an effort to elevate the matter to the US Supreme Court - a move seen by activists at the time as a delay tactic that would jeopardise public health.

Environmentalists who fought to clean up toxic waste sites say they are familiar with that tactic and the frustrations it caused.

“Every time somebody takes a breath of air or touches soil, they're getting poisoned while they're fighting in court,” said Lois Gibbs, who founded the Centre for Health, Environment and Justice, a nonprofit that helps communities fight environmental health threats. “How many lives were changed while they had that fight? How many women weren't able to carry their baby full term or had a birth defect or had a child that got cancer?”

Ms Warren's campaign has defended her past consulting work, saying she was providing services as an expert in a bankruptcy system designed to protect the rights of businesses as well as everyday Americans.

“In her books, speeches, research, and advocacy, Elizabeth has consistently argued for preserving key legal principles that allow bankruptcy to produce the best and fairest distribution of compensation when a company goes broke - including to victims and consumers and including for environmental harms,” said her spokeswoman, Kristen Orthman.

Pointing to the Puget Sound dispute, Ms Orthman added: “Elizabeth wrote a single memo related to a six-year litigation on a legal issue arising from the unique circumstances of a particular case that arguably threatened one of those foundational bankruptcy principles.

“There was no question the rail yard would get cleaned up; the question was which company would pay,” Ms Orthman said. “Elizabeth's memo was not about the merits of environmental laws, which she strongly supports and has fought to expand both in the senate and as a presidential candidate.”

By the time Ms Warren was tapped for the case, the dispute had been building for years.

The case focused on a 50-acre plot that had switched owners several times and was long home to aluminium smelters and pulp mills, contributing to the region's infamous “Tacoma aroma.” Workers cleaned out rail cars on that spot for years, spilling oil into the soil, court records say.

The real estate went to CMC Heartland Partners after the railway went bankrupt in 1977. The parcel was then sold to another firm, Union Pacific, and ultimately to the Port of Tacoma - which demanded a cleanup.

The new state law had been approved by voters and was modelled after a federal law designed to clean up what are known as Superfund sites. It sought to require even past owners of polluted land to contribute to cleanup costs.

Ms Warren presented the case as a philosophical clash. “This is not a simple case of debtor versus creditor . . .” she wrote. “Instead this is [a] question about the scope of the bankruptcy laws.” She added that it is “not even a slight exaggeration” to say the dispute “relates to the very heart of an important part of the legal system.”

The Supreme Court declined to take the case, letting stand lower court rulings against Heartland and requiring it to finance the cleanup.

Ms Warren's argument put her in line with numerous other major corporations that were also seeking a Supreme Court review of the Washington state law.

CMC Heartland Partners' counsel of record for the case was Ken Starr, who at the time also served as the independent counsel examining allegations of misconduct against President Bill Clinton. Ms Orthman said Ms Warren does not recall Mr Starr being her contact for the case, and Mr Starr did not respond to attempts to contact him.

Another top lawyer working for Heartland was Richard Cordray, an Ohio politician and a Warren ally to this day. In an interview, Mr Cordray said neither he nor Ms Warren was arguing that the toxic waste site should not be restored.

“It wasn't like there was going to be nobody responsible for cleaning the place up,” he said. “It's just which of two companies was responsible, and what percentages.”

Ms Warren's campaign pointed to an analysis by Edward Janger, a bankruptcy professor at Brooklyn Law School, whom it asked to review the case after The Washington Post began asking questions about it. Mr Janger said that strong bankruptcy protections like those advocated by Ms Warren made it more likely - not less - that money would be available for cleanups.

“Unless a debtor can address [its] liabilities in the re-organisation, it will typically be forced to liquidate - costing jobs and leaving much less for everybody, including those seeking recovery of environmental cleanup costs,” Mr Janger said.

But Marv Coleman, a retired state official who helped oversee the cleanup, said the companies trying to shift responsibility to each other made the environmental effort that much harder.

“Quite often . . . one company could point the finger to another company,” Mr Coleman said. “That was very common in that period, and that was kind of frustrating.”

David Rieser, who worked on the case for Union Pacific (and had not known about Ms Warren's role), said the new environmental laws were designed to spread costs widely, so that enough money could be raised for expensive cleanups.

“All of these environmental laws were a real change to the liability scheme,” Mr Rieser said. “Even if a company had gotten rid of something 100 years ago, they could still be liable for it under this law.”

Heartland did end up paying. By October 1998, after the Supreme Court decided not to hear the case, the company settled with the Port of Tacoma, records show.

The site is in productive use today, said Scott Hooton, a program manager for the port who oversaw the cleanup from 2007 to 2015. Rows of new cars from Asia are often parked there, ready to be shipped by rail or highway to dealerships across the country. “It's been a successful cleanup,” Mr Hooton said.

Heartland, though, has not been as successful. It declared bankruptcy in 2006.

The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments