Dissolved migrant caravan sign of tougher Guatemala stance

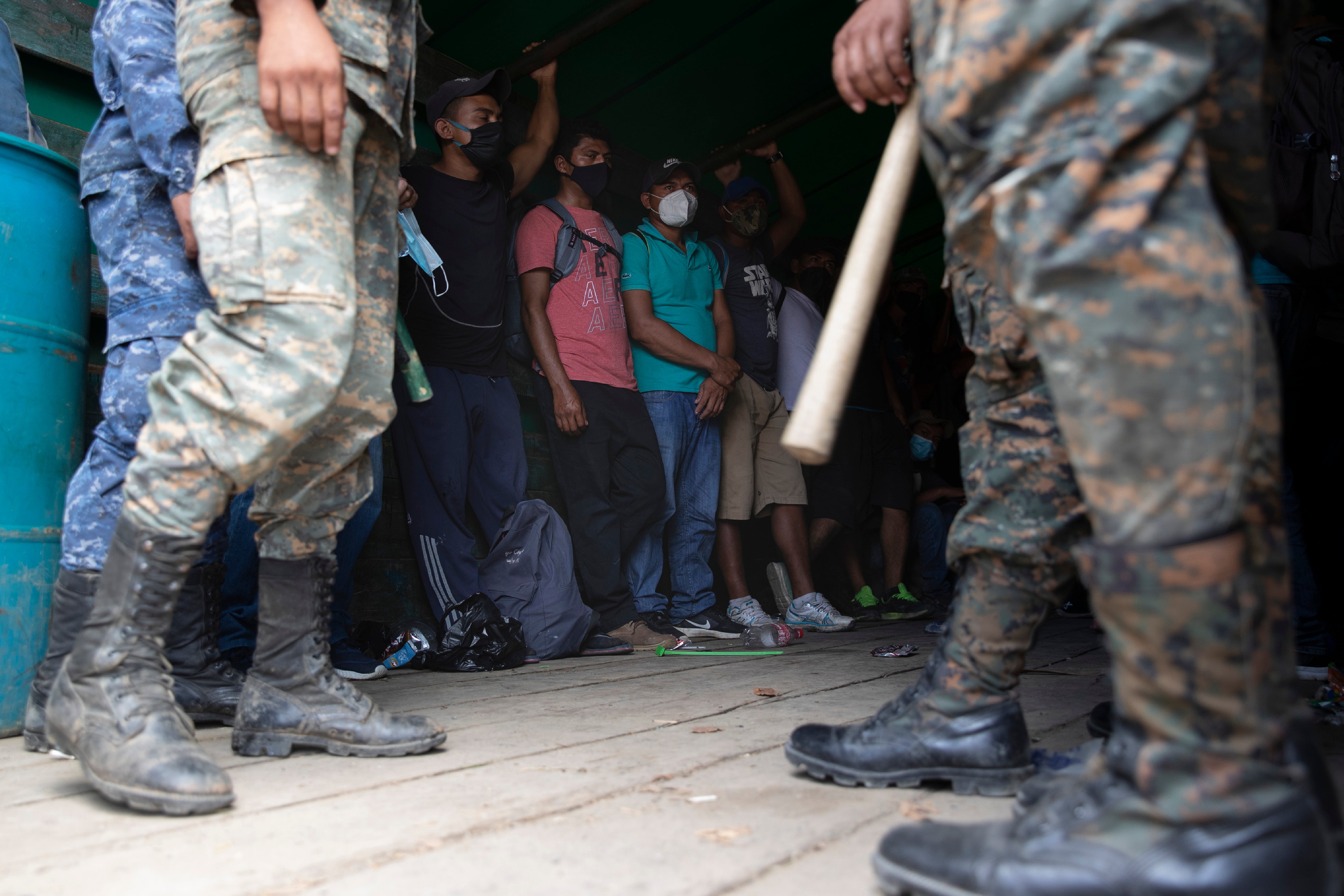

The Guatemalan government’s halt of some 3,000 Honduran migrants who had set out for the United States amid the pandemic signaled that U.S. pressure on immigration continues to extend southward

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The Guatemalan government’s halt of more than 3,000 Honduran migrants who had set out for the United States amid the pandemic signaled that U.S. pressure on immigration continues to extend southward.

Previously, Guatemala did little to stop large movements of migrants crossing its territory. But President Alejandro Giammattei threatened last week to send the latest group back, saying they posed a health risk because of the coronavirus. Over the weekend Guatemala followed through, hauling 3,300 migrants back to the Honduran border.

“The border has definitely moved,” said Ursula Roldan, an immigration expert at Rafael Landivar University. “We already knew the pandemic would be a pretext for states to focus on migrants as an issue of security and health.”

Guatemala’s tougher stance followed Mexico’s hardened efforts that broke up caravans last October and in January at its southern border. Mexico deployed the National Guard during the summer of 2019 to help slow immigration after U.S. President Donald Trump threatened tariffs on all Mexican imports.

Michael Kozak, acting assistant secretary for the U.S. State Department’s Bureau of Western Hemisphere Affairs, went on Twitter to thank Guatemala “for the sustained efforts to mitigate the spread of #Covid19 and stop irregular migration.”

With the U.S. effectively suspending its asylum system at the border and legal crossing reduced to essential traffic, the migrants already faced long odds of entering. But Guatemala’s more assertive position erects yet another set of obstacles at a time when the factors pushing migrants to head north like a lack of job opportunities at home have worsened during the pandemic.

The timing of this caravan and another in 2018, both shortly before important elections in the United States, has raised questions about whether political forces could play a role in their formation. In 2018, the migrant caravan’s movements became fodder for anti-immigrant rhetoric ahead of U.S. congressional elections.

The migrants’ desperation is real and this one set out shortly after Guatemala had reopened borders that had been closed by the pandemic for months. But some voice suspicions that external actors could try to harness the desperation for political agendas.

“I’ve been studying them since November 2018 and I am convinced that there is an organized and external element,” said Guadalupe Correa-Cabrera, an associate professor at George Mason University. “They are not purely organic mobilizations.”

Correa-Cabrera said she had not had a chance to analyze this latest caravan, but in others she identified common actors outside of the migrants themselves who facilitated mass movements. She did not, however, discount the push factors such as poor economies and violent crime that drive people to migrate.

An Associated Press journalist in Honduras recognized three people with the caravan that formed last week who had been present at previous caravans. Two were at the bus station in San Pedro Sula where the migrant group started and one was at the Corinto border crossing where the migrants entered Guatemala.

They appeared to have an informal organizational role, disseminating information about what time migrants would set out and which border crossing they would use. They declined interview requests. In previous caravans, the three were seen with a former local politician from an opposition party who had accompanied migrants but who was not present this time.

As in other cases, plans for the caravan were spread on social networks, primarily Facebook and WhatsApp. Migrants interviewed in Honduras and Guatemala said they decided to join in after seeing the call for the caravan to depart Oct. 1.

On Thursday, hundreds of Honduran migrants pushed past Guatemalan authorities at the border without registering. That night, Giammattei raised the specter of them spreading the coronavirus and said they would be rounded up.

Guatemala's strategy was similar to the one Mexico used earlier. Both avoided potentially dangerous confrontations at the border itself. Instead, interior roadblocks were used to reduce the size of large groups and migrants were permitted to walk and tire before authorities moved against them en masse.

By Saturday, the largest groups in Guatemala had been bused back to the border with Honduras.

Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador said Monday that some small groups of migrants had crossed into Mexico, but that hundreds of immigration agents and national guardsmen put at the border had detained them.

“There are no longer the numbers of people they thought were going to enter the country,” López Obrador said.

Guatemala and Mexico appeared to have coordinated their response. Guatemala’s ambassador to Mexico accompanied Mexican officials inspecting the deployment of Mexican forces at their shared border.

Janeth Rivera, a Honduran migrant who traveled with the latest caravan, said Monday that she was already back home in Honduras. She had tired during the hike north and when faced with the authorities’ roadblock decided to return.

Father Mauro Verzeletti, director of the Casa del Migrante shelter in Guatemala City said migrants are facing more and more difficulties.

“The countries are making it harder and harder for people to leave their countries,” Verzeletti said. “They are turning their policies toward racism, xenophobia and discrimination against migrants.”

But, with calls for new caravans to depart Honduras already circulating, one for Oct. 30 and another in January, Verzeletti said migrants will adapt to meet the changing tactics used by authorities to block their movement north.

“The migrants are going to create another strategy,” he said. “The needs increased with the pandemic and the loss of formal jobs, government corruption increased, so migration will continue.”

___

Associated Press journalists Claudio Escalon in San Pedro Sula, Honduras, and Mark Stevenson and Christopher Sherman in Mexico City contributed to this report.