Democrats make federal election standards a top priority

Democrats are planning to move quickly on one of the first bills of the new Congress, which would set federal election standards that would mandate early voting, same-day registration and other voting rights reforms

Democrats plan to move quickly on one of the first bills of the new Congress, citing the need for federal election standards and other reforms to shore up the foundations of American democracy after a tumultuous post-election period and deadly riot at the Capitol.

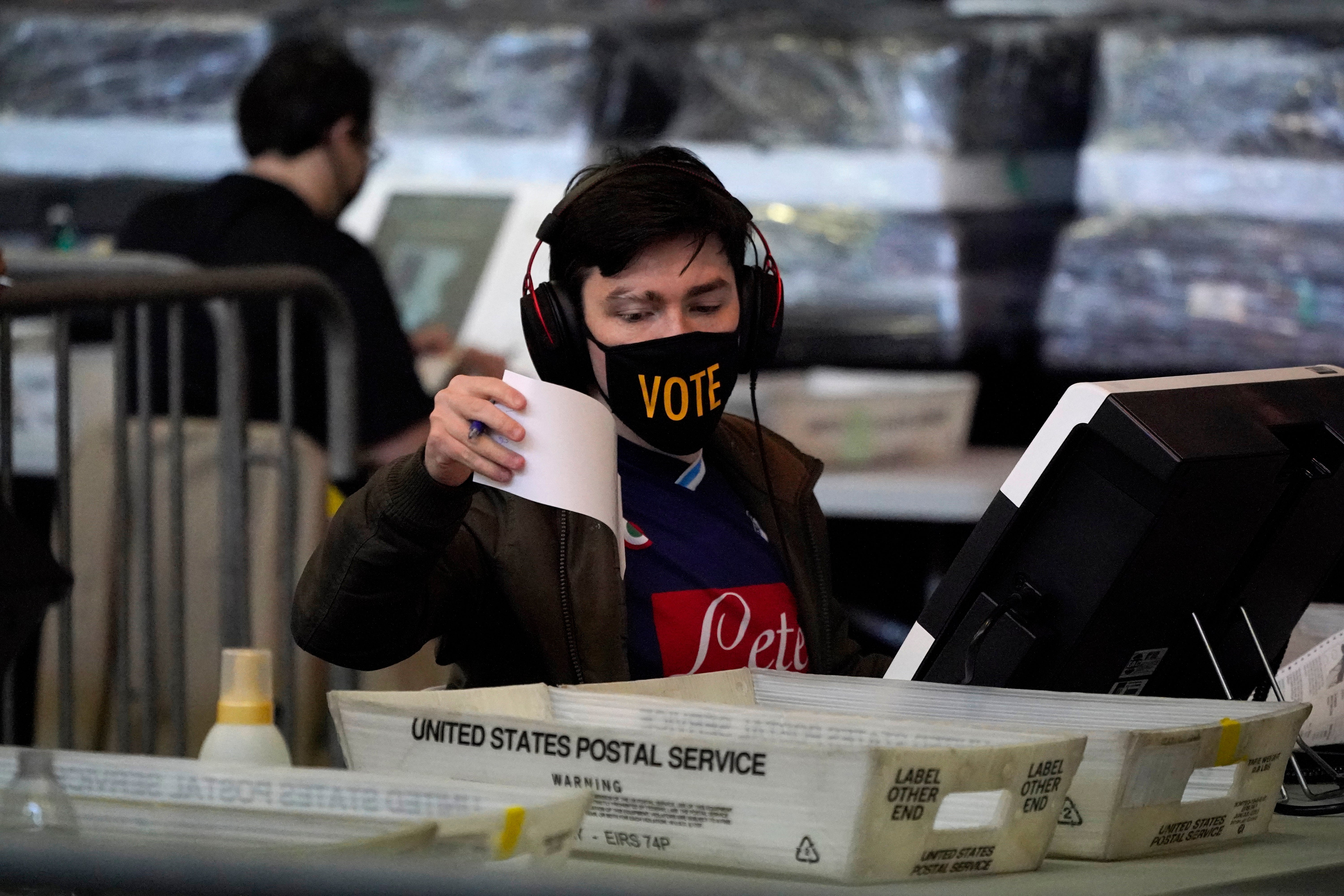

States have long had disparate and contradictory rules for running elections. But the 2020 election, which featured pandemic-related changes to ease voting and then a flood of lawsuits by former President Donald Trump and his allies, underscored the differences from state to state: Mail-in ballots due on Election Day or just postmarked by then? Absentee voting allowed for all or just voters with an excuse? Same-day or advance-only registration?

Democrats, asserting constitutional authority to set the time, place and manner of federal elections, want national rules they say would make voting more uniform, accessible and fair across the nation. The bill would mandate early voting, same-day registration and other long-sought reforms that Republicans reject as federal overreach.

“We have just literally seen an attack on our own democracy,” said U.S. Sen. Amy Klobuchar, a Democrat from Minnesota, referring to the Jan. 6 storming of the Capitol. “I cannot think of a more timely moment to start moving on democracy reform.”

The legislation first introduced two years ago, known as the For the People Act, also would give independent commissions the job of drawing congressional districts, require political groups to disclose high-dollar donors, create reporting requirements for online political ads and, in a rearview nod at Trump, obligate presidents to disclose their tax returns.

Republican opposition was fierce during the last session. At the time, then-Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., labeled it the “Democrat Politician Protection Act” and said in an op-ed that Democrats were seeking to “change the rules of American politics to benefit one party.”

While Democrats control Congress for the first time in a decade, the measure's fate depends on whether enough Republicans can be persuaded to reconsider a bill they have repeatedly rejected. If not, Democrats could decide it's time to take the extraordinary and difficult step of eliminating the Senate filibuster, a procedural tool often used by the minority party to block bills under rules that require 60 votes to advance legislation.

Advocates say the bill is the most consequential piece of voting legislation since the Voting Rights Act of 1965. House Democrats vowed two years ago to make the bill a priority, and they reintroduced it this month as H.R. 1, underscoring its importance to the party.

“People just want to be able to cast their vote without it being an ordeal,” said Rep. John Sarbanes, a Democrat from Maryland who is the lead sponsor of the House bill. “It’s crazy in America that you still have to navigate an obstacle course to get to the ballot box.”

Current plans would have the full House take up the bill as soon as the first week of February. The Senate Rules Committee would then consider a companion bill introduced in the Senate, and a tie vote there could allow it to move out of committee and to the floor as early as next month, said Klobuchar, who is expected to become the committee’s next chair.

A quick vote would be remarkable considering the Senate also is likely to be juggling Trump’s impeachment trial, confirmation of President Joe Biden’s Cabinet choices and another round of coronavirus relief.

While states have long had different voting procedures, the November 2020 election highlighted how the variability could be used to sow doubt about the outcome. The bill’s supporters, which include national voting and civil rights organizations, cited dozens of pre-election lawsuits that challenged procedural rules, such as whether ballots postmarked on Election Day should count.

They also pointed to the post-election litigation Trump and his allies filed to try to get millions of legitimately cast ballots tossed out. Many of those lawsuits targeted election changes intended to make voting easier. That included a Pennsylvania law the state’s Republican-led legislature passed before the pandemic to make absentee ballots available to all registered voters upon request.

Government and election officials repeatedly have described the election as the most secure in U.S. history. Even former U.S. Attorney General Bill Barr, a Trump ally, said before leaving his post that there was no evidence of widespread fraud that would overturn the result.

“The strategy of lying about voter fraud, delegitimizing the election outcome and trying to suppress votes has been unmasked for the illegitimate attack on our democracy that it is, and I think that it opens a lot more doors to real conversations about how to fix our voting system and root out this cancer,” said Wendy Weiser, head of the democracy program at the Brennan Center for Justice, a public policy institute.

Along with the election reform bill, the House two years ago introduced a related bill, now known as the John Lewis Voting Rights Advancement Act in honor of the late civil rights activist and congressman. House Democrats are expected to reintroduce it soon after it had similarly stalled in the Republican-controlled Senate.

That bill would restore a key provision of the Voting Rights Act that had triggered federal scrutiny of election changes in certain states and counties. A 2013 U.S. Supreme Court ruling set aside the method used to identify jurisdictions subject to the provision, known as preclearance, which was used to protect voting rights in places with a history of discrimination.

In general, state election officials have been wary of federal voting requirements. But those serving in states led by Democrats have been more open and want to ensure Congress provides money to help them make system upgrades, which the bill does.

“If you still believe in what we all learned in high school government class, that democracy works best when as many eligible people participate, these are commonsense reforms,” said Sen. Alex Padilla, a Democrat who oversaw California’s elections before being appointed to the seat formerly held by Vice President Kamala Harris.

But Republican officials like Alabama Secretary of State John Merrill remain opposed. Merrill said the federal government’s role is limited and that states must be allowed to innovate and implement their own voting rules.

“Those decisions are best left up to the states, and I think the states are the ones that should determine what course of action they should take,” Merrill said, noting that Alabama has increased voter registration and participation without implementing early voting.

“To just say that everything needs to be uniform, that’s not the United States of America,” Merrill said.

In the Senate, a key question will be whether there is enough Republican support for elements of the voting reform bill to persuade Democrats to break off certain parts of it into smaller legislation. For now, Democrats say they want a floor vote on the full package.

Edward B. Foley, an election law expert at Ohio State University, said Democrats should consider narrow reforms that could gain bipartisan support, cautioning that moving too quickly on a broad bill runs the risk of putting off Republicans.

“It would seem to me at this moment in American history, a precarious moment, the right instinct should be a kind of bipartisanship to rebuild common ground as opposed to ‘Our side won, your side lost and we are off to the races,’” Foley said.

___

Cassidy reported from Atlanta.