Democrats bet on early Latino outreach to avoid '20 pitfalls

Even as Joe Biden flipped heavily Hispanic Arizona to Democratic, clinching the presidency, he underperformed with Latinos voters in many other parts of the country

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

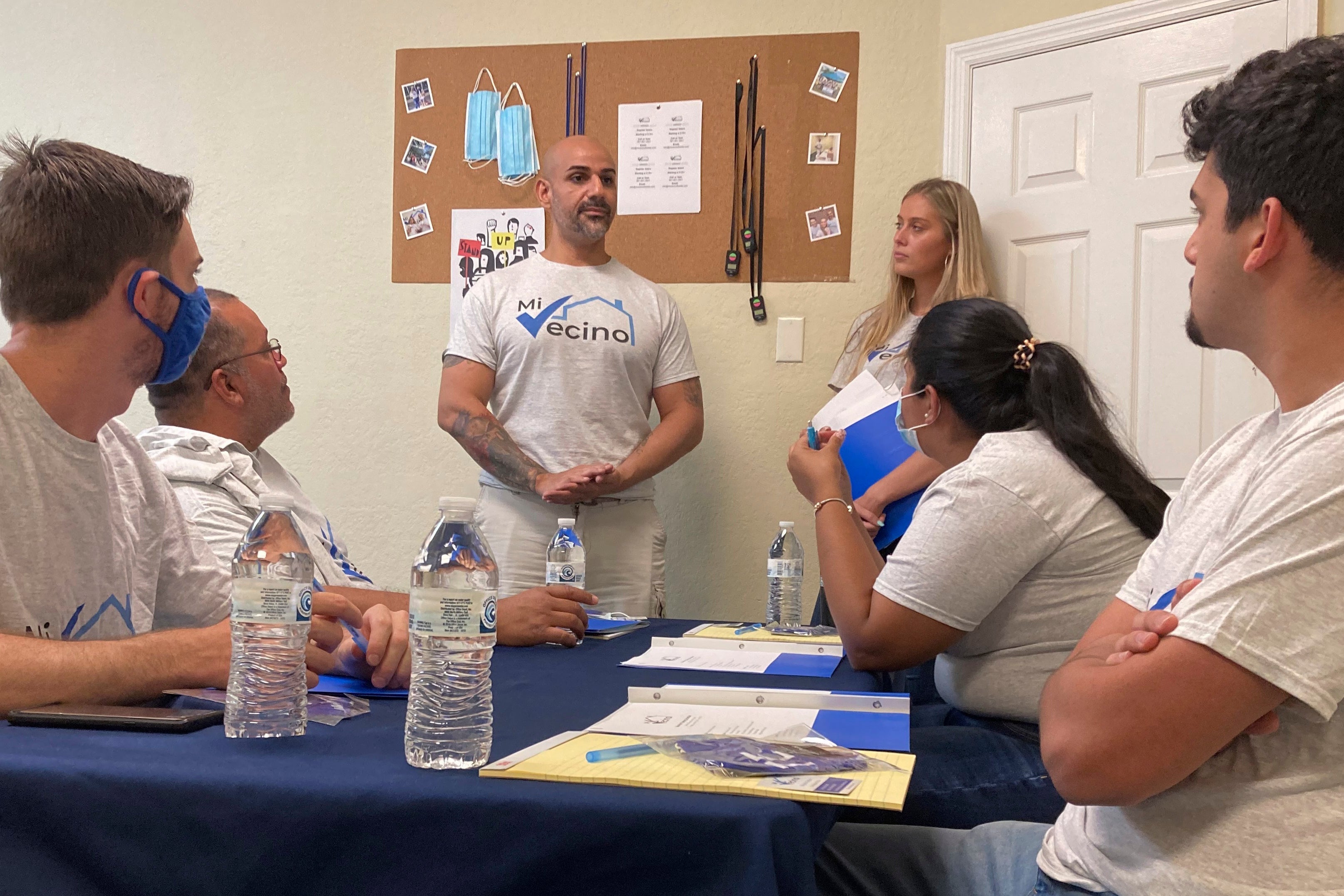

Your support makes all the difference.On a sweaty recent Thursday afternoon, Alex Berrios is instructing his team on how to get people to register to vote. Extend your hand, he says; it makes folks more likely to stop. Smile a lot, that works, too. But immediately take no for an answer so you don’t seem too pushy.

Berrios, co-founder of a new nonprofit, Mi Vecino, or “My Neighbor” has a lot riding on developing the right pitch. His group, which works out of a cramped office in the shadow of Disney World is targeting Latino would-be voters. He is role-playing how best to approach them in front of Walgreens amid games of dominoes at a senior center or outside El Bodegon, a supermarket chain specializing in Colombian products.

Fifteen months before the midterm elections, groups like his are mobilizing across the country — both Democrats who have enjoyed a historic Latino allegiance and Republicans emboldened by gains in 2020 — all trying to lock down the fastest growing segment of the U.S. population.

“We’re not selling cars here,” said Berrios, a onetime boxer who has “fighter” tattooed on his arm and is now vice chairman of the Palm Beach County Democratic Party. “We’re not going anywhere. We’re in the community and we’re staying.”

Even as Joe Biden flipped heavily Hispanic Arizona to Democratic to clinch the presidency last November, he underperformed with many Latino voters elsewhere. And his party lost congressional seats where Spanish is often more common than English, from Miami’s Little Havana to South Texas’ sparsely populated borderlands to the high desert north of Los Angeles.

Nationally, Biden won Latinos by a 59-38 percent margin over Donald Trump, but that was 17 percentage points lower than Hillary Clinton’s 66-28 percent margin in 2016, according to Pew Research Center data.

Republicans say they gained ground with Latinos because Democrats, with their increasingly left-leaning positions, are proving soft on issues like socialism and border security.

But Democrats say a problem for them was that they waited until just before the election to intensify outreach to Latino communities.

“It’s very transactional. Campaigns, they come and they start 30-60 days before an election, then they’re gone,” said Berrios, who left Biden’s campaign after raising concerns about lagging engagement with Hispanic voters.

Berrios says Mi Vecino is trying to change that. And the party has begun an expensive, intensive effort to reach Latinos and other voters of color long before the 2022 elections.

The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee is investing more than $1 million on 48 organizing directors around the country designed to bolster “strategic outreach and build trust” with minority communities in midterm battleground districts, including in Florida and Texas.

Matt Barreto was the Biden campaign’s pollster in charge of Latino message and research and noted that he was only brought on last July. He and other top Democratic advisers are now leading Building Back Together, a play on Biden’s “Build Back Better” post-pandemic campaign slogan, to promote the administration through television and digital advertising.

The initiative first targeted Arizona and Florida as well as two other states with sizeable and growing Latino populations, Nevada and Pennsylvania.

Barreto pointed to recent Gallup polling putting Biden’s approval rating among Hispanics higher than that of all voters, suggesting the campaign is working.

Others, though, are less optimistic.

“The truth is, the money, it hasn’t come as early as it needs to come,” said Giulianna Di Lauro, Florida director of the Hispanic political advocacy group Poder Latinx.

Cecilia Gonzalez was one of Berrios’ trainees and moved to Kissimmee four years ago from Barinas, Venezuela. She said the U.S. could be on a similar path toward her homeland’s collapse, if “we don’t stop electing the wrong people and giving them too much power.”

Republicans aren’t just sitting quietly and watching.

The Republican National Committee says it’s making a seven-figure commitment for outreach to communities of color, including opening regional engagement centers in key congressional districts. The first was inaugurated last month in Orange County, California.

“Hispanics all across the country are Republicans,” said Florida Sen. Rick Scott, who heads the GOP’s campaign arm for the 2022 midterms. “If Republicans reach out to them, we’re going to win.”

Abel Prado, executive director of the Democratic advocacy group Cambio Texas in the Rio Grande Valley, said selling empathic positions like expanding health care access is often tougher than simply boasting about disrupting traditional politics as Trump did.

With Trump not on the 2022 ballot, many of his supporters may simply stay home, he said.

Prado’s organization estimates that getting voter turnout to 65% of registered Rio Grande Valley voters is a “16-20 month endeavor,” which means it should have started already — but it largely hasn’t.

“There are conversations about talking about how to start changing,” Prado said with a laugh.

In the meantime, some conservative groups already have achieved the kind of ever-active Latino outreach campaigns Democrats envision. The Libre Initiative has offices in South Texas and around the country, including near Orlando’s airport.

It advocates for issues like increased school choice and free market economics under the slogan “Limited Government, Unlimited Opportunities” and conducts continuous door-knocking efforts to identify would-be voters. Libre also provides nonpartisan civic assistance, offering free English classes, as well as Spanish-language instruction on health, obtaining U.S. citizenship and entrepreneurship.

Prado said Democratic activists in Texas have begun trying to emulate some of Libre’s work through “deep canvassing,” a process that seeks to have longer, ongoing conversations with people to find out what motivates them — both politically and otherwise.

That’s the kind of multi-year campaign former gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams launched in Georgia, which saw both of its Senate seats flip Democratic in January.

But such efforts take time and aren’t cheap — neither of which delight donors looking for immediate results, Prado said: “This isn’t the stock market where you buy 500 shares of something and triple your money in three weeks.”