Democratic gains in legislative maps might not last long

The surprising advantage Democrats gained during the torturous process of rewriting the nation’s congressional maps may be short lived

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The surprising advantage Democrats gained during the torturous process of rewriting the nation's congressional maps may be short-lived, creating the potential for more frequent clashes over how political power should be distributed across the United States.

As the once-a-decade scramble to draw new legislative lines, a process known as redistricting, nears its conclusion, Democrats have succeeded in shifting the congressional map to the left. The typical U.S. House district now comes close to matching President Joe Biden's 4 percentage point win in 2020. Though the impact may not be seen in this year voting, as Democrats face uphill odds to maintain their House majority, party leaders believe the new maps would make it easier to take the chamber in more favorable elections.

But all that could change.

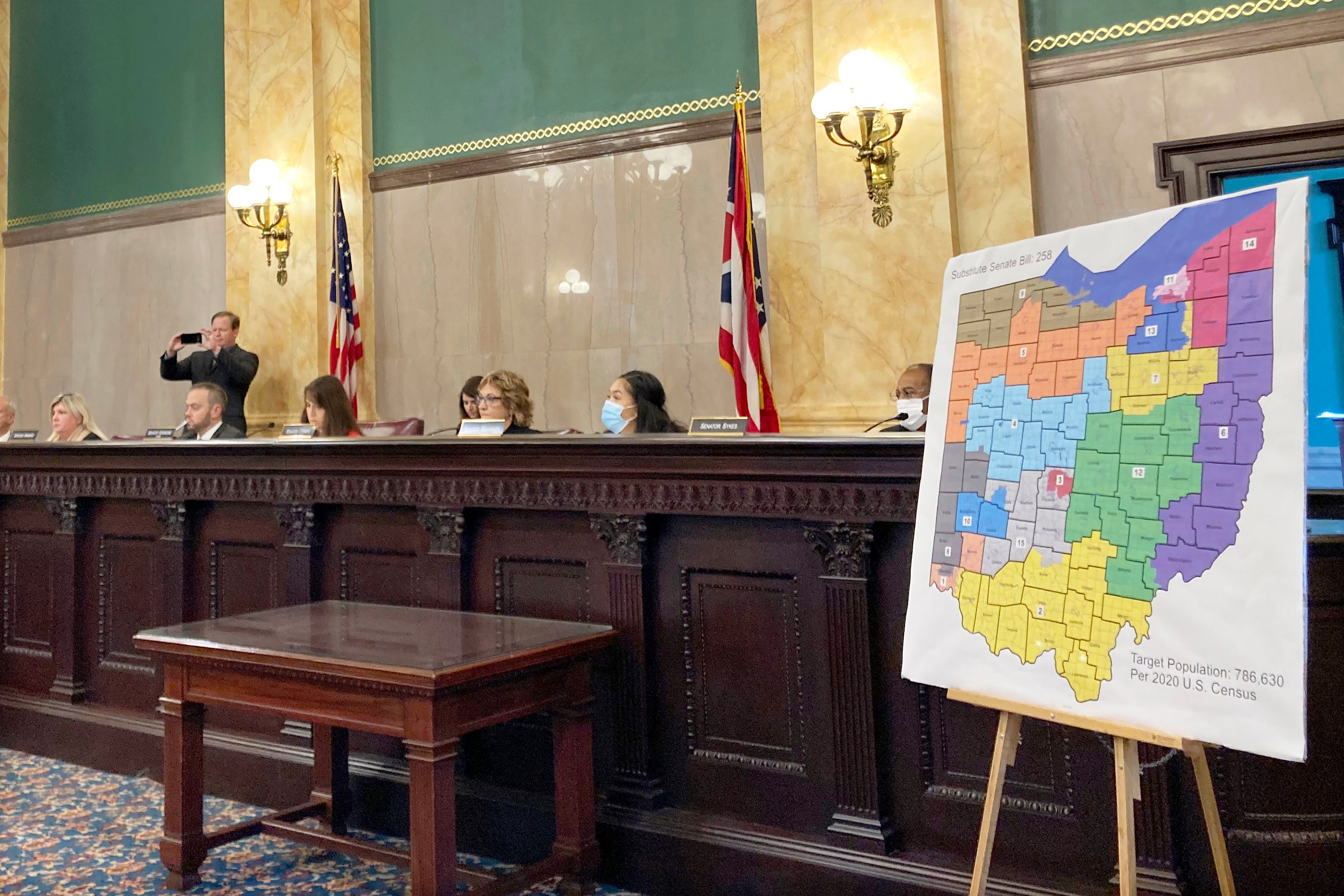

Two major states — North Carolina and Ohio — are already poised to redraw their maps in the next few years. Several cases at the U.S. Supreme Court, meanwhile, could dramatically alter the rules that govern mapmaking nationwide. Those twists could ultimately transform redistricting into a regular political brawl that consumes state capitals already gripped by partisan tensions.

“This is the end of Act I, but there’s a lot more to come in the play,” said Michael Li of the Brennan Center for Justice, which tracks redistricting.

The uncertainty extends to other facets of elections, from the ability to challenge certain voting restrictions in court to whether minorities can have a chance to elect their preferred representatives. But it also leaves a significant asterisk over one of the biggest political twists of the past few years.

Many Democrats began the redistricting cycle haunted by what happened after the Republican wave in 2010. The following year, after the U.S. Census Bureau released its new population count, the GOP had control of drawing new legislative lines in a large number of states, shifting the national congressional map to the right. Democrats worried the same thing would happen in 2021, after the once-a-decade population update.

Republicans, however, had maxed out their gains in many places and turned to shoring up incumbents more than trying to make new seats winnable. Democrats still had far fewer districts to draw than the GOP but controlled more states than in 2011. In those that they did control, Democrats drew aggressive maps to maximize the number of seats they could win.

Republicans and many analysts note that, in doing so, Democrats effectively spread out their voters, making themselves vulnerable to shifts in political coalitions or bad election cycles, as 2022 is expected to be for the party. Still, Democrats say they're satisfied. They count 12 congressional seats that they have shifted into the “likely Democratic” category — though that includes some districts Democrats already represent.

Republicans say they are also happy with how they did. Adam Kincaid, executive director of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, said the party has so far shifted 16 GOP-held seats from being in competitive districts to safely Republican ones. That, he argues, will free up millions of dollars to go after vulnerable Democrats.

“We are exactly in most states where we thought we would be,” Kincaid said. The biggest surprise, he added, is that “Democrats, where they had control, they went wild.”

A couple of significant wild cards remain, with five states lacking official maps.

Florida hasn't finalized its map, stuck in a standoff between Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis and the GOP-controlled Legislature over how aggressively to expand their party's hold on the state's congressional delegation. Ohio's maps are in limbo as the state Supreme Court repeatedly strikes them down as illegal, pro-GOP gerrymanders, or misshapen maps drawn to help one party rather than represent communities.

The GOP is fuming over court intervention in places like Ohio that have helped Democrats, and that's one reason there could be a decadelong redistricting cycle.

Complex litigation over redistricting often drags on for years, sometimes leading to courts ordering new maps. Last decade, Florida, North Carolina, Pennsylvania and Texas all had GOP-drawn maps thrown out by courts and new ones ordered. But legal experts say this cycle may be shaping up to be even more tumultuous and far-reaching.

That's because the conservative majority on the U.S. Supreme Court has signaled its interest in changing some longtime standards that have governed redistricting.

“Their holdings may impact all 50 states in ways that holdings in 2011 didn't,” Doug Spencer, a law professor at the University of Colorado-Boulder, said of the high court.

The first case the Supreme Court took was a challenge to Alabama's Republican-drawn maps last month. A lower court panel cited the Voting Rights Act in ruling that the GOP had to make a second district with enough Democratic-leaning Black voters that they could pick their own representatives without being blocked by whites who vote for the other party. The high court's conservative majority put that ruling on hold, saying it may revise its longtime rules for handling majority-minority districts next year.

Then, last week, the court rejected a GOP appeal of rulings by North Carolina and Pennsylvania's state Supreme Courts that adopted maps Republicans disliked. But four conservative justices — the minimum number required to hear a case — signaled they wanted to rule on the legal theory underlying the challenges, which holds that state legislatures have supreme power in making rules for congressional elections.

There's a wide range of ways the high court could decide both cases, but that already adds uncertainty to a combustible, hyperpartisan environment likely to lead North Carolina and Ohio to redraw their maps later this decade, representing 29 House seats. The unsettled nature of the debate in both states is due to litigation over Republican-drawn maps.

In North Carolina, after a Democratic majority on the state Supreme Court struck down the GOP maps in a 4-3 vote, Republicans vowed to flip the court to their control in November. Indeed, when a lower court panel sketched out a new map for November's election that was more equal than the one that would have given Republicans 10 of the state's 13 seats, the judges labeled it “interim.”

In Ohio, the term-limited GOP chief justice of the state's high court joined Democrats to become the deciding vote to strike down repeated GOP maps as illegal gerrymanders. As in North Carolina, the GOP has vowed revenge at the ballot box, with its primary candidate to replace the chief justice pledging to approve maps drawn by the Republican-controlled legislature.

“We can change those courts,” former New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie, co-chair of the National Republican Redistricting Trust, said in a call with reporters this month. “The game is far from over in North Carolina and Ohio.”

Experts worry that the partisan battles may spread wider than those two states. Mid-decade redistricting is rare but it does happen — Georgia Republicans tweaked their state legislative maps in 2017. In 2003, after Texas Republicans took over the Legislature they gerrymandered that state's maps to benefit the GOP. But with partisan polarization and mistrust higher than in decades, the incentive to squeeze a few more seats out of an improved political or legal position is strong.

Spencer cited Pennsylvania, where the GOP-controlled legislature was blocked by the Democratic governor, kicking map-drawing to the courts. But if Republicans win the governor's race there in November, they may be emboldened to try a whole new sets of the map that are far more tilted to the GOP than the state Supreme Court-approved ones.

If coalitions shift — say, Latino voters continue to trend toward the GOP, or Democrats make further inroads in the suburbs — mid-decade redistricting allows lawmakers to adjust lines to defend their districts.

“The volatility of the country's politics are not to be underestimated and people could adjust to that, and maps could change in a number of states,” Li said.