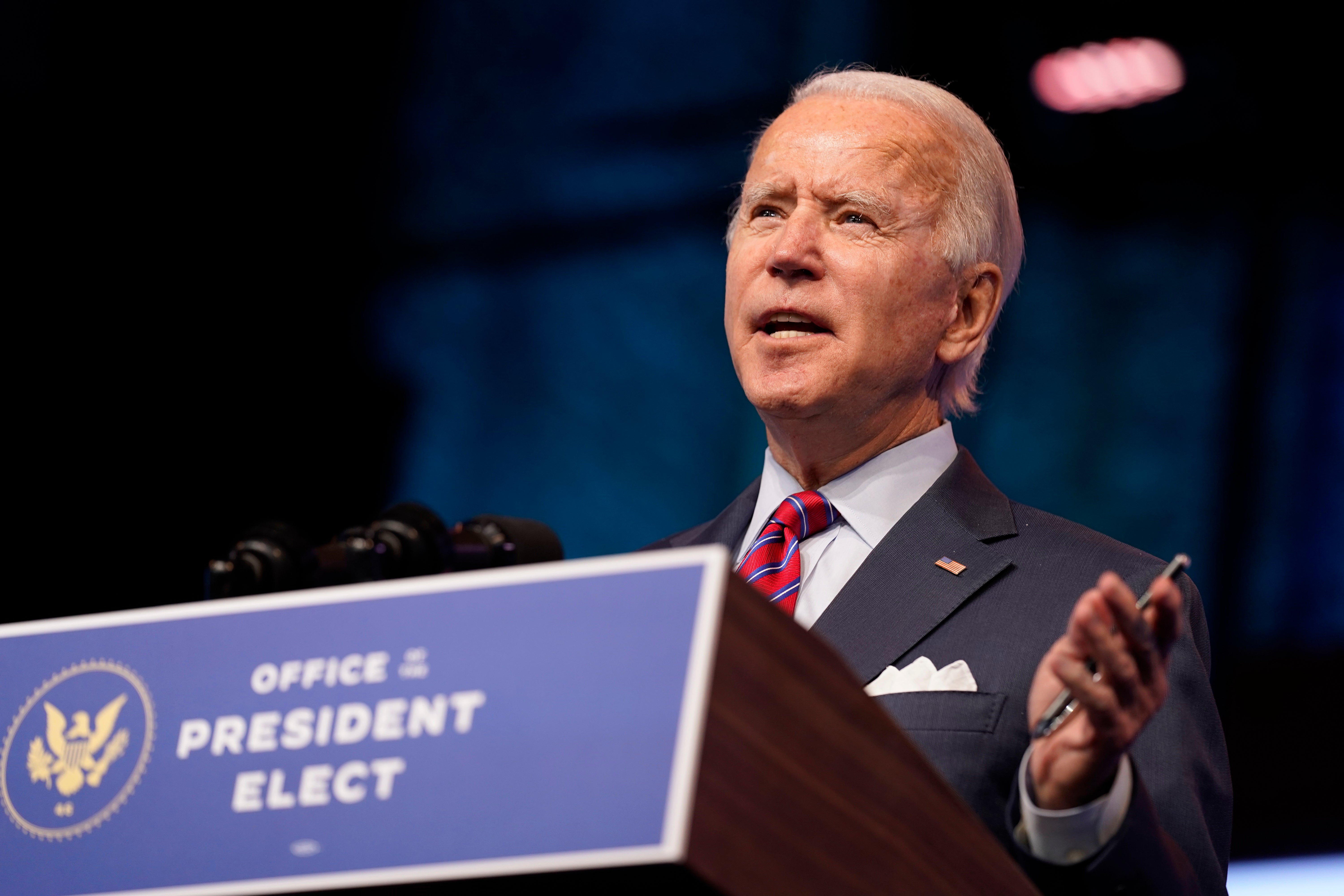

Election results: What is the safe harbour deadline and what does it mean for Biden?

Joe Biden is passing another milestone en route to the White House

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Donald Trump is still fighting his losing battle to overturn Joe Biden’s election victory – but he looks to have failed to head off yet another crucial event in Joe Biden’s path to the presidency.

Other than Wisconsin, every state appears to have met a deadline in federal law that essentially means Congress has to accept the electoral votes that will be cast next week and sent to the Capitol for counting on 6 January. Those votes will elect Mr Biden as the country's next president.

This deadline, which this year falls on Tuesday 8 December, is known as the “safe harbour” provision – a kind of insurance policy by which the states can lock in their electoral votes by certifying their results and resolving any state court legal challenges.

“What federal law requires is that if a state has completed its post-election certification by 8 December, Congress is required to accept those results,” said Rebecca Green, an election law professor at the William & Mary law school in Williamsburg, Virginia.

The Electoral College is a creation of the US Constitution, but Congress sets the date for federal elections and, in the case of the presidency, determines when presidential electors gather in state capitals to vote.

And Congress has also set another deadline, six days before the electors meet, to insulate state results from being challenged in Congress.

By the end of the day, every state is expected to have made its election results official, awarding 306 electoral votes to Mr Biden and 232 to Mr Trump. This does not guarantee that all of them will achieve state harbour status, but enough already have to ensure that Mr Biden is clear of the crucial 270 mark.

Hard deadline

The safe harbour provision played a prominent role in the Bush v Gore case after the 2000 presidential election. The Supreme Court shut down Florida’s state-court-ordered recount because the safe harbour deadline was approaching; the court's opinion was issued on that year’s deadline, 12 December.

Vice President Al Gore conceded the race to then-Texas Governor George W Bush the next day.

In his dissent, Justice Stephen Breyer said the deadline that really mattered was the day on which the Electoral College was scheduled to meet. Whether there was time to conduct a recount by then “is a matter for the state courts to determine,” Breyer wrote.

When Florida's electoral votes, decisive in Mr Bush's victory, reached Congress, several Black members of the House protested – but no senators joined in. It was left to Mr Gore, who presided over the count as president of the Senate, to gavel down the objections from his fellow Democrats.

Chaos averted?

The attention paid this year to the normally obscure safe harbour provision is a function of Mr Trump's unrelenting efforts to challenge the legitimacy of the election. He has refused to concede, made unsupported claims of fraud and called on Republican lawmakers in key states to appoint electors who would vote for him even after those states have certified a Biden win.

But Mr Trump's arguments have gone nowhere in any state where his team have tried them – not in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania or in Wisconsin. Most of his campaign's lawsuits in state courts challenging those Biden victories have been dismissed, with the exception of Wisconsin, where a hearing is scheduled for later this week.

Like the other cases, the lawsuit does not appear to have much chance of succeeding, but because it was filed in accordance with state law procedures for challenging election results, “it's looking to me like Wisconsin is going to miss the safe harbour deadline because of that,” said Edward Foley, a professor of election law at Ohio State University's Moritz School of Law.

Judge Stephen Simanek, appointed to hear the case, has acknowledged that the case would push the state outside the electoral vote safe harbour.

Missing the deadline won't deprive Wisconsin of its 10 electoral votes. Mr Biden’s electors still will meet in Madison on Monday, and there's no reason to expect Congress to refuse their votes. In any case, Mr Biden would still be well clear of the 270 votes he needs even if Wisconsin’s were excluded.

Testing the boundaries

The post-election wrangling over Mr Trump’s defeat will have serious long-term political consequences – but that doesn’t mean his advocates will succeed in keeping him in office.

Lawmakers in Washington could theoretically second-guess the slate of electors from any state that misses the 8 December deadline, Mr Foley said. Already one member of the House of Representatives, Alabama Republican Mo Brooks, has said he will challenge electoral votes for Mr Biden on 6 January. Mr Brooks would need to object in writing and be joined by at least one senator. If that were to happen, both chambers would debate the objections and vote on whether to sustain them.

But even if states were late, unless both houses agreed to the objections, these challenges would fail.

It is unclear what the safe harbour deadline means for Mr Trump’s lawsuits against various states trying to get them to overturn their results. The cases brought on his behalf by both personally appointed lawyers Rudy Giuliani and Jenna Ellis have yielded disaster after disaster, with even Republican governors who recently counted as staunch Trump backers insisting on following the law and thereby drawing the president’s ire.

With Mr Giuliani hospitalised with Covid-19, the official campaign effort is somewhat hobbled. Meanwhile, the officially unsanctioned pro-Trump cases led by conspiracy theorist lawyer Sidney Powell have met with even more ridicule than the Giuliani-Ellis cases, and are similarly having no success. If their aim was to slow down states’ certification processes and thereby blow past the safe harbour deadline, they have failed.

However, they may well succeed in another goal: warping the Trump base’s trust in the system to the point where tens of millions of Americans will never believe Mr Biden is a legitimately elected president.

The unwillingness of Mr Trump and his supporters to concede is dangerous, said Mr Foley, because "in an electoral competition, one side wins, one side loses and it's essential that the losing side accepts the winner’s victory. What is really being challenged right now is our capacity to play by those rules."