Colombia faces presidential choice between leftist, populist

Colombians can count on one thing: The country’s presidential politics will drastically change after Sunday’s runoff election

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Colombians can count on one thing: The country’s presidential politics will drastically change after Sunday’s runoff election.

The contest in the South American country lacks a front-runner and presents voters with a choice between the man who could become the first leftist to lead the nation and a populist millionaire who promises to end corruption.

The guaranteed departure from long-governing centrist or right-leaning presidents has led both sides to play into people’s fears. Want a former rebel as president or an unpredictable businessman?

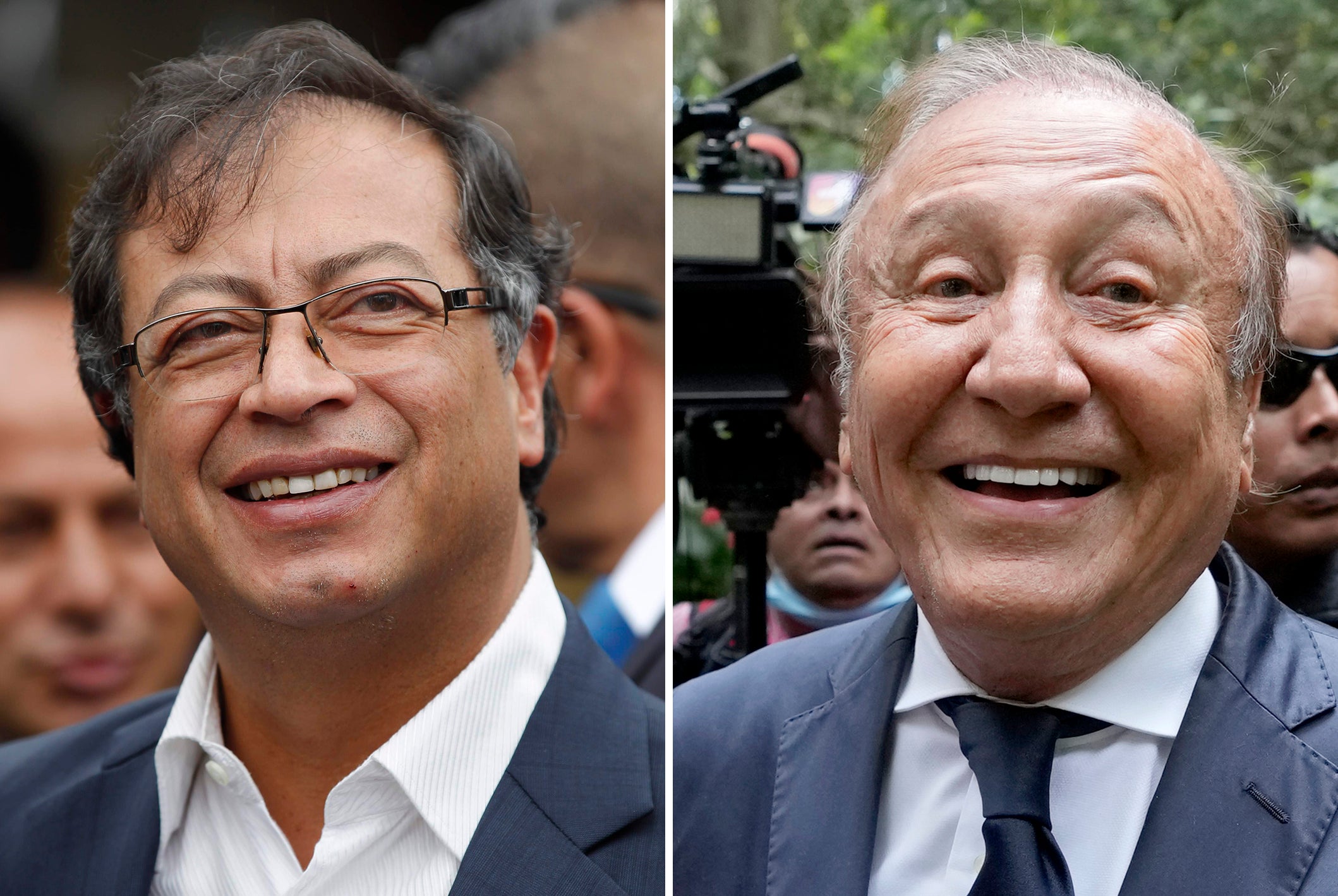

Polls show Gustavo Petro and Rodolfo Hernández — both former mayors — practically tied since advancing to the runoff following the May 29 first-round election in which they beat four other candidates. They haven’t debated each other, but a court ordered them Wednesday to do so.

Petro, a senator, is in his third attempt to become president, and his strongest rival is again not another candidate but voters’ marginalization of the left due to its perceived association with the nation’s armed conflict. He was once a rebel with the now-defunct M-19 movement and was granted amnesty after being jailed for his involvement with the group.

“Anyone but Petro,” reads graffiti in northern Bogota, the capital city he governed in the mid-2010s. Petro, 62, obtained 40% of the votes during last month’s election and Hernández 28%, but the difference quickly narrowed as Hernández began to garner the so-called antipetrista votes.

“The worst-case scenario that Petro could have faced is Rodolfo Hernández. Why? Because (Hernández) offers a change, he is also someone anti-establishment,” said Silvana Amaya, a senior analyst with the firm Control Risks. “What Colombians chose in the first round are the two candidates that represent change. They’re saying, and they’re sending the message, that they are tired of the system. They’re tired of the status quo and they are tired of the traditional politicians telling them what to do.”

Should Petro win, he would join the list of leftist political victories in Latin America fueled by voters’ thirst for change at a time of deep dissatisfaction with economic conditions and widening inequality. Chile, Peru and Honduras elected leftist presidents in 2021, and in Brazil, former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is leading the polls for this year’s presidential election.

Petro has promised to make significant adjustments to the economy, including tax reform, and to change how Colombia fights drug cartels and other armed groups.

As mayor, he generated conflicting opinions. People praised his ambitious social projects but also criticized his ability to deliver on promises and some improvised decisions. His mandate ended in controversy after the Attorney General’s Office removed him and barred him from holding public office for 15 years for “very serious” faults in the implementation of a city cleanup program.

The dispute ended before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which in 2020 declared Colombia responsible for violations of Petro’s political rights.

He has tried to assure Colombians he won't follow the path of some other leftist leaders in the region who engineered changes to term limit laws to keep themselves in power.

“Rest assured that I will not seek reelection,” Petro said recently. He added he “will respect the laws. ... Listen carefully, this includes respecting the right to private property,” clarifying that he will not expropriate properties.

Meanwhile, Hernández, 77, is not affiliated with any major political party, and through an austere campaign waged mostly on social media, he promises to reduce wasteful government spending and go after corrupt officials. He rode a wave of disgust at the country’s condition, surging late in the campaign past more conventional candidates and shocking many when he finished second in the first-round contest.

Hernández got rich in real estate after growing up on a small farm. He says he has covered the costs of his campaign rather than depending on donations.

He entered politics in 2015 when he ran for mayor of the north-central city of Bucaramanga and won against all odds. He resigned shortly before the end of his tenure after being suspended by the Attorney General’s Office for alleged participation in political activities, which public officials are prohibited from doing.

“Some people believe that if he was successful as a businessman, he could be successful as a politician, and he could be successful running the country,” Amaya said. “And he was very successful cleaning the financial status of (Bucaramanga) while he was a mayor. The problem is that he ... doesn’t understand how institutions work. Sometimes he has a very erratic personality, and he just says, ‘I don’t care how to do things, or what you need to do things, just do it’ and that could potentially disrespect the rule of law.”

His strategist, Ángel Becassino, told The Associated Press that Hernández “is more wise than knowledgeable about things.”

“He is a very restless man who is very interested in... knowing about things, having knowledge, but he is a man who has accumulated mileage that gives him a common-sense criterion that, let’s say, makes it easier for him to clearly identify where the problems are,” Becassino said.

Colombians are voting amid widespread discontent over rising inequality, inflation and violence.

A Gallup poll last month showed 75% of Colombians believe the country is heading in the wrong direction and only 27% approve of President Iván Duque, who was not eligible to seek reelection. A 2021 poll by Gallup found 60% of those questioned were finding it hard to get by on their income.

The pandemic set back the country’s anti-poverty efforts by at least a decade. Official figures show that 39% of Colombia’s 51.6 million residents lived on less than $89 a month last year, which was a slight improvement from 42.5% in 2020.

Inflation in April reached its highest levels in two decades. Duque’s administration said April’s 9.2% rate was part of a global inflationary phenomenon, but the argument did nothing to tame discontent over increasing food prices.

___

Garcia Cano reported from Caracas, Venezuela.