The US police driving manoeuvre that has killed 30 since 2016

The controversial move sees cop cars forcing assailants off the road or into obstacles. Shaun Raviv and John Sullivan investigate

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Shortly before midnight on March 28, 2017, a silver Dodge Caravan streaked past Highway Patrol Trooper Dustin Motsinger as he sat parked along a stretch of highway in rural North Carolina. Motsinger raced after the speeding van. The driver stopped, but as the trooper climbed out of his cruiser, the van drove off. Motsinger gave chase.

Inside the van that night, 15-year-old Osiel Carbajal was at the wheel. His passengers: his 16-year-old sister, her 15-year-old boyfriend and a 15-year-old friend. The teens had taken the van without permission from Carbajal’s mother in nearby Morven.

“Possibly 55, they’re all over the place,” Motsinger told his supervisor on the radio, using the code for a drunken driver.

“If you can PIT him, go ahead,” said the supervisor.

As the teens crossed the Anson County line at 100 mph, Motsinger caught up with them. Then, he bumped his Dodge Charger into the right rear quarter panel of the Caravan, sending it off the road.

The van flipped and began to cartwheel, landing almost 500ft away. The force sheared the wheels from the left side of the vehicle. The impact hurled three of the teens from the Caravan. Two of them died. One broke his back. The driver suffered minor injuries.

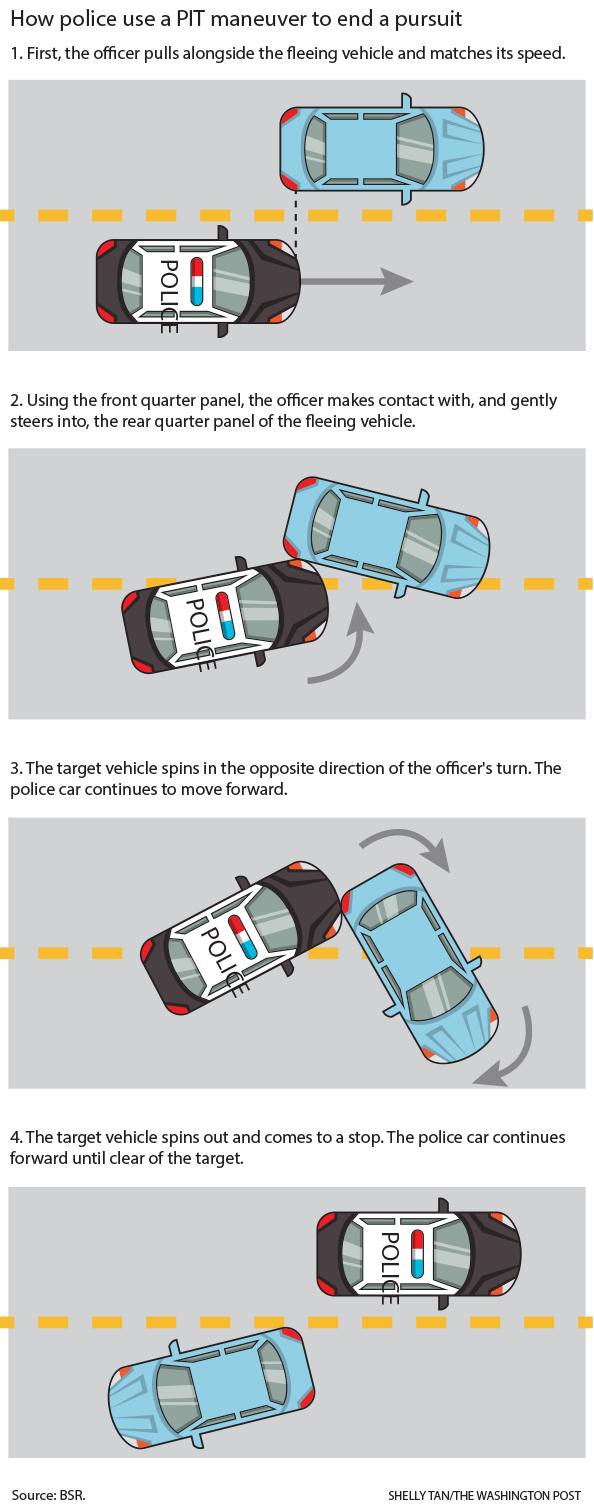

The trooper’s manoeuvre was no accident – it was a PIT, or precision immobilisation technique, a tactical driving manoeuvre for which he’d been trained.

In a successful PIT, the pursuing officer uses a cruiser to push the fleeing vehicle’s rear end sideways, sending it into a spin and ending the pursuit. But the tactic can have deadly consequences.

This year, nine people have been killed across the US in PIT manoeuvres, including a 16-year-old who was driving a stolen car in Longmont, Colorado, and a driver and passenger who were being chased by police for speeding in Creek County, Oklahoma. Last month, a 29-year-old suspected drunken driver who fled a traffic stop in Coweta County, Georgia, died after a PIT manoeuvre.

Since 2016, at least 30 people have died and hundreds have been injured – including some officers – when police used the manoeuvre to end pursuits, according to an investigation by The Washington Post.

Out of those deaths, 18 came after officers attempted to stop vehicles for minor traffic violations such as speeding. In eight cases, police were pursuing a stolen car, and in two, drivers were suspected of serious felonies. Two other drivers had been reported as suicidal.

Ten of the 30 killed were passengers in the fleeing vehicles; four were bystanders or suspected of being a victim of a crime.

Half of the people who died in the crashes were people of colour: nine black, four Hispanic and one Native American. Fourteen of those killed were white, and the race of two could not be determined.

The total number of people who have been killed or injured as a result of the manoeuvre is unknown because the nation’s more than 18,000 police departments are not required by the federal government to keep track.

The death on May 25 of George Floyd under the knee of a Minneapolis police officer has led to renewed public scrutiny of violent police tactics, including shootings, stun-gun use and chokehold administration. But the PIT manoeuvre – also a potentially deadly use of force by police – has not received the same attention, despite its risk and widespread adoption by departments nationwide.

The statistics about PIT deaths and injuries since 2016 come from news reports and records from the 100 largest city police departments and 49 state police agencies. Responses were received from 142 of them. Most departments were able to provide only policies on whether they used the manoeuvre. Many were unable to say how often chases ended in PITs.

One of the nine drivers killed this year was 34-year-old Justin Battenfield, a man whose family said he was mentally disabled and loved to drive the roads around his home in Van Buren, Arkansas.

On an April morning, Battenfield, in a Dodge Ram, did not stop at a traffic signal and then began to flee when a US Forest Service officer attempted to stop him. Arkansas State Trooper Michael Shawn Ellis picked up the pursuit. Dashboard-camera video from the trooper’s car captured Battenfield as he swerved into the path of oncoming traffic. “Get this car stopped as soon as there’s an opening,” a supervisor told Ellis over the radio.

Ellis hit Battenfield’s truck at 109 mph, sending both vehicles into a tumble. Battenfield’s truck landed on its roof, and acted as a ramp for the trooper’s car, launching it into the air, where it sliced through two street lamps.

The PIT ... is supposed to be a controlled manoeuvre based on all of the factors at that second the law enforcement officer’s bumper makes contact with the vehicle

Battenfield died, and Ellis suffered “non-life-threatening injuries,” according to state police.

“They should have backed off and he would have come on home,” said Carol Henson, Battenfield’s mother. “Then they could have come up and got him.”

An Arkansas State Patrol spokesperson said the department regretted the loss of life, but emphasised that the PIT often hinges on the unpredictable behaviour of the fleeing driver.

“The PIT ... is supposed to be a controlled manoeuvre based on all of the factors at that second the law enforcement officer’s bumper makes contact with the vehicle,” said Bill Sadler. ”That’s what everything is based on. If the suspect changes the dynamics in any way, it could very easily turn bad, and no question about it.” He declined to make Ellis available for comment.

When performed at slower speeds – generally 35 to 45 mph – the manoeuvre can be safe and effective to end pursuits, experts said.

The Los Angeles Police Department reports that it has used PIT manoeuvres since 2005 without a death or serious injury.

The department does not permit the manoeuvre at over 35 mph. Officers are not allowed to chase or PIT vehicles that are fleeing minor traffic violations. Its use is limited to pursuits involving dangerous felons or people suspected of driving drunk.

“It allows us to safeguard the surrounding community while capturing an offender who has committed a serious offence,” Los Angeles Police Chief Michel Moore said. He described it as an important tool in specific circumstances.

“We recognise that over that speed the dynamic nature and the physics of an engagement can result in a vehicle that becomes a risk to the public, the occupants and the officers,” Moore said.

At greater speeds, the manoeuvre has launched cars into traffic and trees, and in one case killed a woman in Tift County, Georgia, as she stood in her front yard.

“When you start getting into high speeds it gets very dangerous,” said Rick Giovengo, who has studied the use of the PIT as a senior research analyst at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Centres in Glynco, Georgia, where federal, state, local and tribal officers from across the country train to use the PIT.

Despite the risk, there has been little national research on its safety or benefits.

In 2006, the Georgia Association of Chiefs of Police conducted one of the few studies of the manoeuvre as part of a wider look at police pursuits in the state. The report concluded that “the PIT manoeuvre is controlled and predictable” but “in certain circumstances could result in serious injury or death”. Those circumstances, the report said, included a PIT on a driver who is not wearing a seat belt, a PIT that ejected people from the fleeing vehicle or a PIT that knocked the fleeing car into a roll.

The Police Executive Research Forum, a Washington-based think tank that advises police chiefs on policy, has examined the lethal use of firearms and police pursuits, but not the use of the PIT.

“We generally don’t recommend it,” said Chuck Wexler, executive director of the group. “You wouldn’t want to endanger the officer or the person you’re pursuing unless you had some reason to believe they were going to commit a violent crime.”

Karen Blum, a law professor at Suffolk University Law School, studied the tactic for the National Police Accountability Project, which filed a brief in a Supreme Court case brought by a man who was paralysed in 2001 during an attempted PIT by a Georgia police officer.

“Over a certain speed there is nothing precise about a PIT manoeuvre,” Blum said. “It amounts to a ramming that turns two heavy vehicles into deadly projectiles.”

Last year, the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office in Florida engaged in more than 200 police pursuits, ending 61 of them with PITs, according to an annual report from the office.

One of those ended in a death: Louis Warren Reese, an 84-year-old retired Navy veteran who had been kidnapped.

Shortly after 2pm on January 2, 2019, a gunman robbed the Lucky Charms Arcade in Jacksonville and fled on foot into Reese’s backyard. Police surrounded Reese’s property. The man suspected in the stickup, Lawrence Hall, allegedly broke into Reese’s house, shoved him into the back of his Dodge SUV parked in the garage, opened the door and sped away.

When it’s utilised within policy and within state law, we feel we’re doing a good job and that there are no reservations, certainly we would never want a death to occur

As a police helicopter and patrol cars followed the fleeing SUV, police searched for Reese – unaware that he was in the back of the SUV, according to police reports.

During the chase – which reached speeds in excess of 100 mph – Hall drove into an officer attempting to place tyre deflation sticks in the road. Another officer attempted to PIT the SUV, but failed and crashed. Eight miles from where the chase began, an officer performed a PIT on the fleeing vehicle, according to police reports.

The PIT sent the SUV into a concrete telephone pole, and the car split in two. Power lines fell onto its roof, and the car began to burn. Police rescued Hall – and then realised Reese also was in the car.

“The responding officers extinguished the fire, and it was at this time they discovered an elderly male ... in the back seat of the vehicle,” officers wrote in a report. Reese, a deacon at his church, suffered a collapsed lung and fractures, including a broken leg, arm and spine, his family told a local television station. He died in the hospital a week later. His family did not respond to requests for comment.

Hall and two deputies suffered serious injuries. The deputies were awarded medals, and Hall was charged with attempted murder and kidnapping. The case is pending. The Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office declined to comment on the crash or their use of the manoeuvre, citing an ongoing investigation into the crimes.

Throughout the 1990s, a few departments nationwide embraced the tactic, which is known by various names, including tactical vehicle intervention, or TVI. In 1996, a Tampa Police sergeant on a search for new tactics to safely end pursuits learned of its use by police in Fairfax County, Virginia.

“I can teach a chimpanzee how to do this,” he later told the Tampa Bay Times. Other departments began using PIT, including the Georgia State Patrol.

Since 1997, the patrol has performed more than 1,500 PIT manoeuvres, according to court and agency records, logging the first fatality in 1998. Since then, at least 34 people have been killed, including seven since 2016.

“When it’s utilised within policy and within state law, we feel we’re doing a good job and that there are no reservations,” said Lieutenant Stephanie Stallings, a Georgia State Patrol spokesperson. “Certainly we would never want a death to occur from any manoeuvre that we utilise but unfortunately there are cases when death is a result.”

Other departments across the state have adopted the PIT manoeuvre – in some cases leading to disastrous outcomes.

In September, a Whitfield County, Georgia, deputy used a PIT to end his pursuit of a stolen car. The 21-year-old driver, Makayla Whitt, was ejected and thrown 50ft and her left arm was severed below the elbow, according to police reports. Whitt could not be reached for comment.

In June 2018, in Monroe County, Georgia, a sheriff’s deputy pulled over 28-year-old Guadalupe Garcia because of a suspected window-tinting violation, according to local news reports. Garcia fled and the deputy performed a PIT at nearly 76 mph, knocking his Toyota Camry into trees, throwing Garcia and his 19-year-old nephew from the car. Garcia died, and his nephew said he was hospitalised for at least two weeks.

The Monroe County Sheriff’s Department did not respond to requests for comment.

Priscilla Villaneueva, Garcia’s girlfriend and the mother of their three children, said he had been in trouble with police and was afraid of being deported. He had been arrested before on drug charges. “I think they should have tried another method of slowing the car down,” Villaneueva said. “The PIT was done at such a high speed.”

Outside Atlanta, on December 4, 2018, South Fulton police attempted to pull over a Hyundai Sonata that had been reported stolen.

The driver, 19-year-old Emmitt Daniels, sped off, nearly striking an officer who had just exited his police vehicle. Officers gave chase, pursuing Daniels for about three miles and reaching speeds of at least 65 mph, according to police reports.

As Daniels passed a cluster of townhouses, one of the officers performed a PIT manoeuvre, using his Dodge Charger to strike the right rear corner of the Hyundai, sending it spinning across a sidewalk. The car splintered a utility pole and rolled up a steep embankment, coming to a stop. Daniels sprinted into the townhouses, escaping police.

As police investigated, they found a shoe near the scene of the crash, which they suspected Daniels lost while fleeing, according to a local news report.

Five weeks later a landscaper working in the area found the body of 41-year-old Marcus McCrary, who had been struck and killed by the out-of-control Hyundai. McCrary’s body, which was found hidden behind bushes, was missing its lower left leg, the landscaper said.

Police later found the lower part of McCrary’s leg in a wheel well of the Hyundai in an impound lot.

McCrary’s twin sister, Miracle Walker, said that the day of the crash, McCrary was on the way to her house, only a few blocks away. When he did not show up, she tried to find him.

She said she now knows the exact moment her brother died: The lights in her house went out when Daniels’s vehicle knocked over the power lines.

“The officers said speeds were up to 90 miles an hour,” Walker said, adding both the police and Daniels are to blame. “There’s not any given time you can go down that street and there aren’t pedestrians.”

Daniels was arrested a few weeks later on charges of murder and homicide by vehicle for the death of McCrary, according to court documents. The case is ongoing. An attorney for Daniels did not respond to a request for comment.

South Fulton Police Chief Keith Meadows also did not respond to requests for comment.

The risks of using the PIT have divided departments. Of the 142 law enforcement agencies that responded to requests for information, 74 said they do not use the manoeuvre. One would not say.

“We do not use the PIT manoeuvre, and the reason is safety,” said Paul Linders, a spokesperson for the St Paul Police Department in Minnesota. “If our officers were to PIT a vehicle in a residential area, the vehicle could wind up in a yard, playground or storefront. We don’t want to take the chance of injuring an innocent bystander to end a pursuit that way.”

The New York State Police do not use the tactic, “due to the potential danger it poses for the targeted vehicle occupants, the pursuing Troopers, and the motoring public,” according to Beau Duffy, a spokesperson for department.

Fairfax County police, one of the first departments to embrace the manoeuvre, said they have trained many agencies across the country to use it.

“We can do a PIT with minimal damage or no damage besides paint transfer between two vehicles and get the car to stop where we want it to stop,” said 2nd Lieutenant Jay Jackson, who is in charge of the centre and track in Chantilly, Virginia, where Fairfax police conduct pursuit training.

The size and weight of the RV forced him and the RV across the central reservation and into the southbound lanes of traffic

Officers gradually learn how to match the speed of a fleeing vehicle and make contact with the vehicle in motion, Jackson said. Officers cannot use the tactic on the streets until they have completed eight successful PITs on the track. They are required to recertify every three years.

Jackson said that at 45 mph and below, the fleeing cars will spin 180 degrees into the next lane. Above that speed, events are less predictable, he said.

Thirty of the 67 agencies that use the PIT manoeuvre allow their officers to do so at any speed; 26 of the agencies have a speed restriction, according to surveys. Eleven agencies provided no information about whether they have speed restrictions.

Indiana State Police, for example, prohibit its use at more than 50 mph. State police in Iowa and California limit the PIT to speeds of 35 mph and under.

Many agencies suggest officers receive approval from a supervisor before performing a PIT. The Utah Highway Patrol has a one-paragraph policy that requires officers who use the PIT to “act within the bounds of legality, good judgment and accepted practices”.

Georgia State Patrol’s pursuit policy says the officer should consider the condition of the road, visibility, pedestrian and vehicle traffic, the type of vehicle and whether there are passengers in the fleeing vehicle. The patrol prohibits PITs on motorcycles or ATVs. But there is no limit on speed, deferring to officers to decide what is “reasonable”.

Nebraska State Patrol warns against the use of PITs on pickup trucks with passengers in the cargo area or larger vehicles, but it has no limits on speed.

Some agencies allow officers to PIT over specified speeds only if they believe use of deadly force is justified.

“Some places and legal experts will say a PIT over 55 mph constitutes the use of deadly force, and some will say 45. It’s somewhat arbitrary,” said Geoffrey Alpert, a professor of criminology and criminal justice at the University of South Carolina, and co-author of the book Evaluating Police Uses of Force.

In Albuquerque, New Mexico, police allow officers to PIT vehicles at speeds greater than 35 mph when they believe deadly force is warranted. That was the case when police used the manoeuvre on a Gulf Stream Touring RV.

Shortly after 7pm on June 20, 2017, police tried to arrest David Barber at an RV park on illegal-gun-possession and battery charges. Barber fled in a stolen 26ft RV, ripping the sewer hose and electrical cords from their connections and driving through a metal gate.

At first, police decided not to chase Barber because a police plane was monitoring the RV from above, Sergeant Albert Sandoval said later in a deposition. But when Barber nearly hit an officer, Sandoval ordered police to give chase. For about 45 minutes, and at speeds of up to 70 mph, police chased the RV, which struck at least five vehicles.

After the RV drove through a busy intersection, an officer pulled alongside it and touched the front right side of his Ford Expedition to the rear driver’s side of the RV. He turned his steering wheel to the right.

“The RV did not ‘spin out’ as he expected it would,” according to a later investigation by police. Instead, “the size and weight of the RV forced him and the RV across the median [central reservation] and into the southbound lanes of traffic.”

The officer’s Expedition collided with three other cars, but Barber kept going, driving the RV over the central reservation and back into the northbound traffic lanes. Another officer conducted a second PIT on the RV at about 62 mph, records show.

This time the PIT manoeuvre forced the RV to jump the central reservation and strike an oncoming Chevy Malibu. Driving the sedan was Tito Pacheco, a single father of three teenagers.

Pacheco died of his injuries three weeks later. His children and brother sued Albuquerque police, settling for $500,000 (£376,000), according to a city spokesperson. Pacheco’s family did not respond to a request for comment.

Barber was arrested and charged with crimes, including first-degree murder for Pacheco’s death. The case is ongoing.

“If we didn’t do anything to stop him at that time, in that RV, the chances of him killing somebody were very high,” Sandoval said in a deposition for the lawsuit, describing his order to stop the RV.

“Once I gave that directive ... I knew that these officers were going to utilise their vehicles to strike that vehicle, which could cause death or great bodily harm to the driver,” he said.

Gilbert Gallegos, an Albuquerque police spokesperson, said there have been many policy changes at the department since the crash.

“I’m not aware of any other major incident dealing with PIT manoeuvres,” Gallegos said. “We also have additional driver training for officers involved in crashes, and we recently got a new driving simulator to help with training.”

In the weeks before Motsinger, the North Carolina Highway Patrol trooper, used a PIT to stop the minivan full of teens, he had ended two other pursuits with the tactic. In one, he sent a driver into a ditch at 65 mph and caused $3,300 (£2,500) in damage to his patrol car. He was driving a loaner vehicle the night he rammed the van, records show.

The teens were on the road that night because Maria Carbajal and her mother had a fight about Maria’s boyfriend, who lived with her family. Angry, Maria packed some clothes, took her mother’s van and left home with her brother Osiel, her boyfriend and another friend.

Teresa Chaparro, Maria and Osiel’s mother, waited to call the police. She was afraid they would arrest the children. But after two days, Chaparro went to the Wadesboro police station and talked to an officer, who sent out an alert that the teens were missing.

The next night, Osiel, who had no licence, was driving 70 mph in a 45 mph zone on Highway 74 when Motsinger saw the van speed past and gave chase.

Osiel pulled over at first, but said that one of the teens in the car warned: If they get into trouble, they would be arrested. Everyone told him to go, he said. Osiel sped off. They were only a few miles from his home.

“I felt like if I could get to where my mom was she could help me,” Osiel said.

Motsinger asked a dispatcher to contact police ahead and ask if they had “stop sticks,” spiked strips that could be dropped into the roadway to disable the van’s tyres. No, she replied, according to audio of the radio conversation.

He asked whether he should PIT the van. A supervisor asked whether there were other people in the vehicle.

At the time, North Carolina had no speed restriction on PIT manoeuvres used by officers such as Motsinger, who had undergone more extensive training. But the policy prohibited troopers from using the manoeuvre if the fleeing vehicle was believed to be carrying “children or other innocent passengers”.

“I saw at least one other occupant,” Motsinger said over the radio. “I don’t know how many.” Motsinger added that traffic was light and the area was clear.

“You think he’s 55?” the supervisor asked, using police radio code for an intoxicated driver.

Motsinger said he did. The supervisor gave him the go-ahead to PIT.

Why would you PIT manoeuvre a car over 100 mph? What did you accomplish in this? You killed two innocent people

Seventeen miles into the chase, Motsinger closed in, and his front left quarter panel caught the back right side of the van. Osiel lost control and the minivan flipped end over end until it came to rest in the woods.

The rear seat of the van, where Maria Carbajal and her boyfriend, Jonathan Thomas, were sitting, broke free, throwing them from the vehicle. Police told Chaparro that Maria had died clutching Thomas, who suffered a broken vertebrae.

A friend, Kandy Castrejon, who had been sitting in the front passenger seat also was ejected. Castrejon died a few days later.

A report by the North Carolina Highway Patrol’s Collision Reconstruction Unit said the “manoeuvre was performed correctly in this crash”.

A North Carolina Highway Patrol spokesperson called the deaths “tragic” but declined to comment further on the case. Motsinger could not be reached for comment and the department declined to make him available.

Chaparro said that the night of the crash she had been praying in church and had a chill, and knew Maria was in trouble. When she got home, her youngest daughter said that the teens had stopped by the house, but were scared they were in trouble and again left. She was getting ready for bed after midnight when the call came about the crash.

When she arrived at the hospital, she saw teams of doctors huddled around a thin girl and recognised Kandy Castrejon’s mother nearby. In the next room she saw Thomas, Maria’s boyfriend. She went to the final room and saw her son Osiel sitting up on a table.

Osiel asked about his sister. But she was already dead.

After the crash, the North Carolina State Bureau of Investigation reviewed Motsinger’s use of the PIT and turned the findings over to the state attorney general’s office, which cleared Motsinger of any wrongdoing.

“It appears that all viable means of stopping the vehicle had been exhausted and the likelihood of serious injury or fatality to the public remained a major concern prior to Trooper Motsinger’s decision to utilise the PIT as a means to disable the vehicle,” the attorney general’s office wrote in a February 2018 letter about its decision.

“Trooper Motsinger was forced to make a split second judgment about the amount of force necessary in a situation that was very tense, uncertain and rapidly evolving.”

The families of Maria and Kandy sued the state, alleging that Motsinger used excessive force, was reckless, and violated department policies. Motsinger, they contended, should have been aware that four teens were in the van. The case was settled in May for an undisclosed amount, records show.

Thomas said that after the crash he began to have haunting flashes of his friends flying around inside the van.

He said he was overcome with regret for not doing more to stop Osiel from speeding away when they were stopped. Osiel was charged with a felony for eluding police and later pleaded guilty to a juvenile charge, according to attorneys who represent the family. Osiel was not intoxicated, the lawyers said.

“It does not make sense to me that the police did that,” Thomas said. “Why would you PIT manoeuvre a car over 100 mph? What did you accomplish in this? You killed two innocent people who had their whole life ahead of them because someone else decided to speed off.”

As a result of the crash, the North Carolina Highway Patrol in July 2017 revised its policy on the use of PIT: Troopers are not allowed to PIT vehicles at more than 55 mph unless the fleeing driver has committed a felony or the use of deadly force is warranted.

Chaparro said she regrets calling the police.

“They did not need to kill my child,” she said. “For what?” she asked through a translator. “I had not realised that Saturday when we went to work that it would be the last time I would talk to my daughter.”

The Washington Post’s Julie Tate, Steven Rich, Ana Chacin and Justine Coleman contributed to this report, which was published in partnership with the Investigative Reporting Workshop, where Chacin and Coleman were fellows

© The Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments