Elizabeth Warren has a plan for everything. But running for president wasn’t always on the to-do list

The former school teacher is going after the ‘diamonds, Rembrandts, and yachts’ of America’s wealthy elite, but she just wants a sliver of those goods

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Elizabeth Warren seems to have a plan for everything, and she wants everyone to know it.

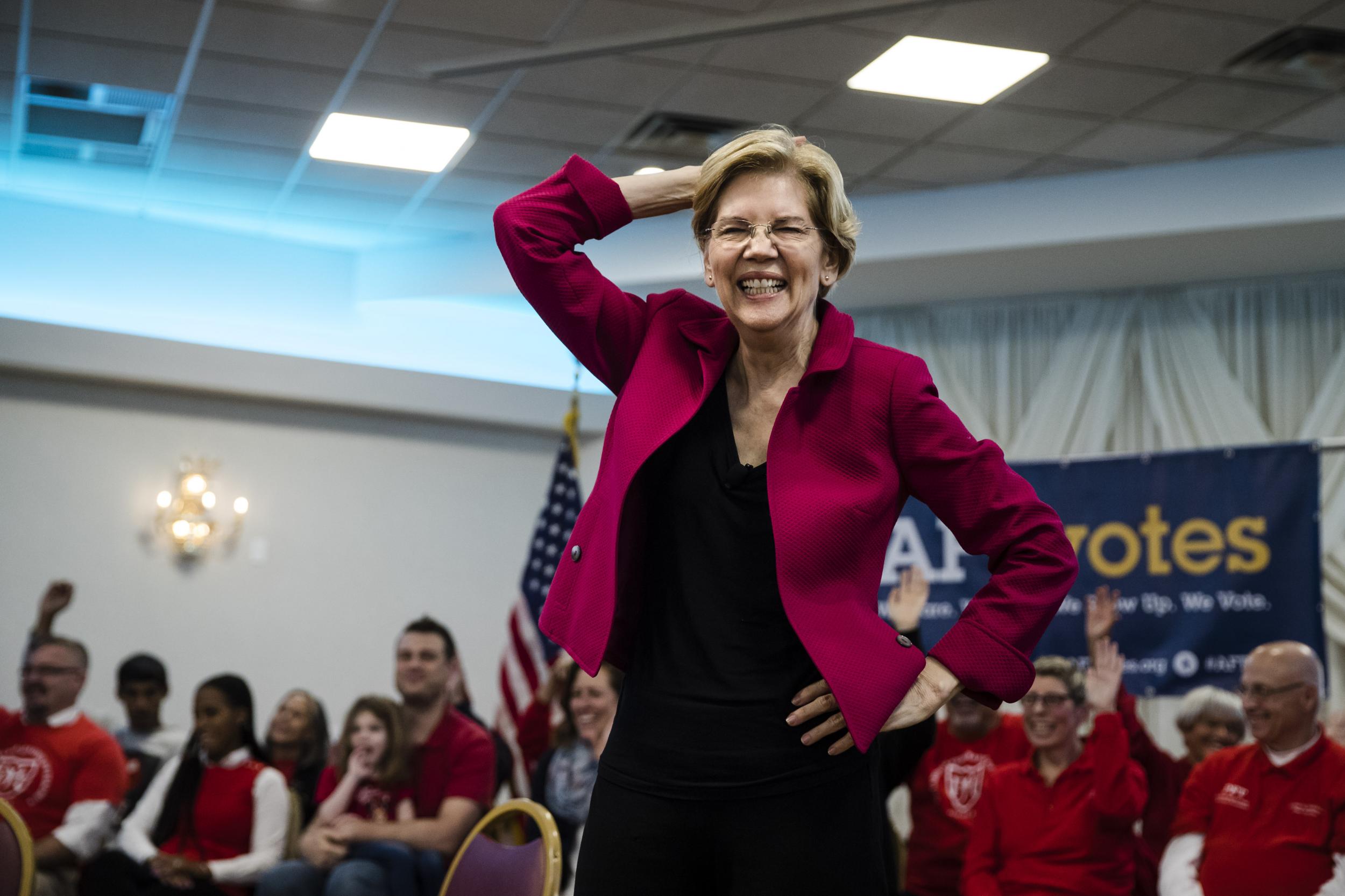

Speaking to a crowd of teachers and students at a recent campaign stop in Philadelphia, the presidential candidate and US senator stuck to that script, repeating the mantra her campaign has adopted as she makes her case for big, structural changes in America.

“I have a plan for that – in fact I have several,” she claimed to knowing nods on her first trip to the state of Pennsylvania on the 2020 trail.

But the woman who is seeking out the nation’s highest office, the one who has set herself apart from the pack with dozens of detailed policy proposals, is the first to admit that being president of the United States actually wasn’t part of her plan, at least not originally.

“I am, like, the most unlikely person to ever run for president,” said Ms Warren, who was first out of the 2020 gate with an announcement on New Year’s Eve, to the crowd that just a half an hour later would form a long line for big-smile selfies that wrapped around the room. “Never thought I would do this.”

It’s a modest conceit for a sitting US senator, especially one who is a leading figure in a progressive movement that has surged over the past decade.

That’s not to mention the resume she has built since her seemingly reluctant entrance into national politics in 2010 when she spearheaded the creation the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau — one of the financial sector’s most hated agencies — only to be blocked from running the thing by a Washington elite fearful of what the former Harvard law professor might do with an agency aimed at keeping Wall Street accountable.

But, standing in that union hall on a recent rainy afternoon in front of all those teachers, Ms Warren had a story to tell that’s more than just her policies.

“I had this dream I wanted to be a public school teacher. And, so, like a lot of Americans, I have a story that kind of twists and turns. It doesn’t take a straight line,” she said, describing her “first love” in life: teaching.

Born in Oklahoma City in 1949, the 69-year-old senior Massachusetts senator said her life was anything but glamorous growing up. Her middle class parents struggled with medical bills after her father had a heart attack, a condition that was only exacerbated when his hours were cut as a salesman. They lost the family station wagon. They almost lost their home.

The twisting and turning came next, and Ms Warren has a way of telling the story in short segments, pulling the audience with her on the journey that would see her nearly not achieving that dream of being a public school teacher, achieving that dream, and then losing that dream before finding her way back.

“So here goes my story: I got a scholarship to college. Yay!” she said, raising her fist triumphantly to applause.

“Then at 19 we fell in love. Yay!” she said with marked less enthusiasm, and the audience catches the drift, laughing along.

“Oh, and got married to the first husband. Ehh,” she continued, riding dangerously close to some understanding boos. “Dropped out of school. Oh…”

After the exit from school, Ms Warren the found herself a job answering phones, a job she says would have been a good life, but not the one she wanted. So, she eventually enrolled at the University of Houston for $450 a semester, and later became a special education teacher.

“I loved it, and I would probably still be doing it today but back in the day, before unions, the principal, by the time we got to the end of the first year, I was visibly pregnant,” she said. “And the principal did what principals did in those days: they wished you luck, showed you the door, and hired someone else for the job.

“And there went my dream.”

Of course, that’s not where Ms Warren’s story ends, and that wasn’t the end of her dream. She went on to move to the east coast, where she attended law school at Rutgers University. She practised law after that for “45 minutes” before going back to her “first love, teaching”, trading kids for adults studying law at Harvard University.

For the next several decades, she says she focused on money — commercial law, corporate finance law, economics and bankruptcy — before, finally, finding herself in Washington pushing the Obama administration to put in place a consumer financial watchdog in an effort that would then propel her, against the odds, into a US Senate seat, and, now, a long-shot presidential election campaign.

Sitting far below the front runner in the Democratic field, Joe Biden, it’s easy to see why Ms Warren tells her story of meandering triumph. While the former vice president instantly found himself in first place in the polls with nearly 40 per cent support after announcing his candidature, Ms Warren is pushing third place with less than 10 per cent in most polls – sometimes she’s in fourth place. And there are some 20 other candidates not far behind, doing everything they can to stand out, hot on her heels.

Sometimes, at least for Ms Warren, standing out can be a liability, and she’s learned that the hard way. While she has often tried to focus on her big policy proposals, she’s also been attacked repeatedly by Donald Trump and Republicans for claiming Native American ancestry on an official national law school directory. And, just last year she fanned those flames further, by releasing DNA test results that showed she perhaps had distant Native American ancestry generations ago — a stunt that stirred fury in the Cherokee Nation who said the senator’s claim of connection to the tribe was “inappropriate”, even as she tried to put the whole thing to bed.

Plus, even without the Native American ancestry fiasco, Ms Warren is always a target for pundits in the Biden wing of the Democratic Party, who think the former vice president is a safer bet as he won’t rock the boat as much and perhaps won’t alienate big money donors in the pharmaceutical industry, on Wall Street and elsewhere who help pay for the billion-dollar presidential campaigns that America has come to know as the price of admission to the White House these days.

So, facing those attacks, it helps to have the alternative narrative: she’s a midwestern middle class gal who is used to being the underdog. She’s the hero in waiting, who knows more than almost anyone how wealth and power have amassed in America while regular Joes get left behind. And, she’s the Robin Hood in the race planning that first big heist, waiting for the best opportunity to pounce.

“There’s been one central question that has always been at the heart of my work, and that is what’s happening to working families in America,” she said. “Why is America’s middle class being hollowed out? Why is opportunity shrinking in this country? Why is it that for people who work every bit as hard as those a generation earlier that the road is getting steeper and rockier and for people of colour even steeper and even rockier. That’s been my work.”

And, she has plans for all of that: get people into college for free and eliminate student debt for around 95 per cent of Americans, revitalise American unions, make sure Americans all get affordable health insurance and actually target the special interests that have created a system that benefits the wealthy and not the middle class.

The rich will pick up the tab, with a 2 per cent tax on wealth above $50m that will pay for much of her plans, she says.

“How about, for the ultra-zillionaires, we include in their property tax the diamonds, the Rembrandts and the yachts?” Ms Warren said in Philly, describing the tax she says is better understood as a property tax for the ultra wealthy. “Right?”

In her estimation, the current system works pretty well for those at the top. Big financial institutions are doing great, just not the workers getting “ripped off” as they try to make it between paydays. Big oil companies aren’t worried about padding their pocket books while the rest of us are watching in fear as climate change comes “bearing down upon us”.

And, for the woman who persisted, that’s enough to pull her from her dream job in the classroom.

“But, you know, there comes a time, when the fight comes to your front door, and you see what it’s about, and you say there’s no more standing on the sidelines,” she said in Philadelphia, concluding her story and, perhaps, setting up its next chapter.

“This is our chance to build an America that is an America of our best values. This is our chance to build the America in which not just those at the top, but everybody, gets a real chance to build a life.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments