‘18 more months, baby. Then I’m in Iceland’: The group helping trans people to leave the US

Rynn Willgohs knew something was wrong when she got ‘culture shock’ from a tolerant society. Now she works to help people like her flee the country in search of something better. Holly Baxter reports on the trans people leaving America — and the people who think they’re traitors to the cause

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Rynn Willgohs tells the local police department ahead of time when an article comes out about her. “I’ve been stalked. People will take a picture of somebody’s house and then send it to you on social media to let you know they know where you live,” she says. “There was one trans girl that somebody started their house on fire. So yeah, Fargo is kind of like the Wild West still in a lot of ways. But 18 more months, baby. Then I’m in Iceland.”

She laughs, but the issue isn’t actually all that funny to her. A few months ago, Willgohs started a Facebook group that grew into a nonprofit: TRANSport, which helps relocate trans people from the US to other, more tolerant parts of the world. Her mission is to move people out of the “Wild West” and into a place where they don’t have to keep looking over their shoulders.

TRANSport is now a phenomenon, and all the transgender founders on the board plan to move abroad themselves. Some cisgender members will stay in the country to keep things running. TRANSport’s website only went live a couple of weeks ago, complete with forms to fill out for any trans people who think they might need their services. They’ve already had more applications than they expected: “several, sometimes dozens per day,” says Willgohs. Right now, they’re only serving their local region: North Dakota, Minnesota, and some parts of South Dakota. But they hope that over time – whether via their own organization or through inspiring others to take similar action – their efforts will go national.

Relocation is a serious business, and narrowing down the options in terms of where one might move is complex. How does someone who has spent most of their lives in rural North Dakota choose between Sweden, Finland and Denmark, for instance? For Rynn, Iceland was the clear choice: She visited a year ago, not long after she’d come out, and got “culture shock” from how progressive it was.

“The society was so different,” she says. “I mean, the spaces that are accepting of transgender females over there – it was just unbelievable. It was actually culture shock for me. It was hard to wrap my head around – I think I got more weird looks for having purple hair than I did for being transgender. Seriously, it was weird. It was the opposite of being in the United States in terms of being discriminated against. It was so inclusive that it was off-putting.” She laughs. “And it was really hard wrapping my head around how it was such a non-issue. And so dealing with that society, it was like: I’d already made up my mind. I mean, I’m 50 years old, I’ve only just started living my life authentically, and I want to enjoy it to the fullest.”

Rynn’s life since coming out had been hard. She ran educational workshops for people curious about trans issues and had worked hard to advocate for LGBT+ rights. But the politics were against her, and the people who disagreed with her were becoming bolder and more intimidating. She was followed, sent hateful messages, and even once attacked while going about her business. Being trans in North Dakota was exhausting, and she wanted to be able to live her life in peace: “I’m old. I want to live my life. I want to pursue my hobbies, you know – marathon running, aerial silks. I want to find a man that I want to spend the rest of my life with. And still do the advocacy and the activism and help people. But I want to do it in a place where I don’t have to fear for my life.”

The future as Willgohs sees it is grim: recent political developments in the US concerning LGBT+ rights – bathroom bills, drag bans,CPAC speeches about eradicating “transgenderism” – and Supreme Court judgments like the overturning of Roe v Wade point to a bleak future, she says. She thinks that America could be mere months away from stopping all access to gender-affirming medication, which would force thousands into detransition. Now is the time, she believes, to be getting out.

So how does it work, in terms of logistics? For Willgohs, everything is in order: “I have gone through the process of cashing out all my 401k’s and securing housing in Iceland through a conservator since I’m not a citizen.” Her residency permit awaits when she arrives; she is not planning to formally seek asylum, though she does imagine that will be the route for a lot of other people using TRANSport. She plans to work in construction once she gets there, because it’s an easily transferrable skill that is always in demand.

When TRANSport helps other people to relocate, they take a cautious and practical approach. “The precursor steps that we’re taking before people leave are making sure that all other identity documents are in order – name changes, gender marker changes – we make sure they have all their medical records… and then the other thing too is making sure that people have access to continue their medications when they go overseas… One of the things that I always tell people is, if you’re on estrogen, start doing injections. Because it’s easier to stockpile injections than the pills.”

Willgohs and her compatriots at TRANSport restrict their work to their local region specifically because they make sure to meet with the people using their services face-to-face. That’s partly due to safeguarding and partly to make sure that their money is going where people say it is. In Minnesota, for example, changing your name is a costly and time-consuming process, involving multiple documents, witnesses, a court appearance with two witnesses, and then hoop-jumping to get ahold of a modified passport. TRANSport will help with all of that, so long as they know exactly who they’re working with and have met them before: “We’re not just going to send somebody money to get their passport and then hope it’s going to the right person.”

“Plus, we want to do interviews. There’s some mental health professionals that we’ve set an arrangement up with if they don’t already have a mental health diagnosis,” Willgohs adds. “And I know that sounds super gatekeepy and cringey, but there’s a reason for it. If you go to a country and you’re going to declare asylum, it’s going to be so much easier if you go over there with a phone book’s weight of medical records saying: Yes, I’m transgender, and this is my proof. It’s going to be so much easier. And then the other thing too is with the mental health folks, talking with people, they can kind of do an informal assessment to make sure that somebody’s going to be able to have the mental fortitude to be able to go to a whole new country and be able to make it work. Because we don’t want to jeopardize somebody’s health and safety by just willy-nilly sending people overseas.”

There’s an interactive map on TRANSport’s website that collates trans-friendly organizations in countries across the world, as well as other information about “gender recognition, marriage, anti-hate laws, access to gender-affirming care”. TRANSport has connections with some of these organizations; there’s an “entire college campus in Sweden” that helps people come to the country, she says. And whenever somebody is successfully relocated using TRANSport’s services, it’s on the condition that they will become a local contact on the ground for other trans people looking to move there, too.

Is it a genius solution to a growing problem in America, or is it just giving up? Willgohs and her co-founders have experienced some backlash from their own community. What message is it sending, such critics ask, when your activism involves simply packing your bags and leaving? “I get a lot of that,” says Willgohs, “…but you don’t have to physically occupy the space in the United States to still get things done. And I think that’s a really narrow view of somebody, saying that they don’t need to leave or they’re traitors or whatever… and there’s no way I’m going to stop fighting. But if you’re forced into detransition, if you’re forced into mental health institutionalization, or I mean, the way some of these laws are written, like the [Tennessee] drag queen bill – that would make it illegal to be transgender in public. So then you’re charged with a sex crime. And how are you going to fight from jail? How are you going to be an activist or advocate from prison?”

Wynne Nowland is the chair and CEO of insurance firm Bradley and Parker. She came out as trans in 2017, in middle age, while working in a conservative industry (“You know, I’m a throwback. Other than being trans, I’m a throwback,” she laughs. “I’ve been with the same company for 38 years.”) Though she believes “it’s considerably worse” for trans people in the US now than it was when she first came out, she also has a lot of optimism for the future – and she is skeptical about the solutions put forward by organizations like TRANSport.

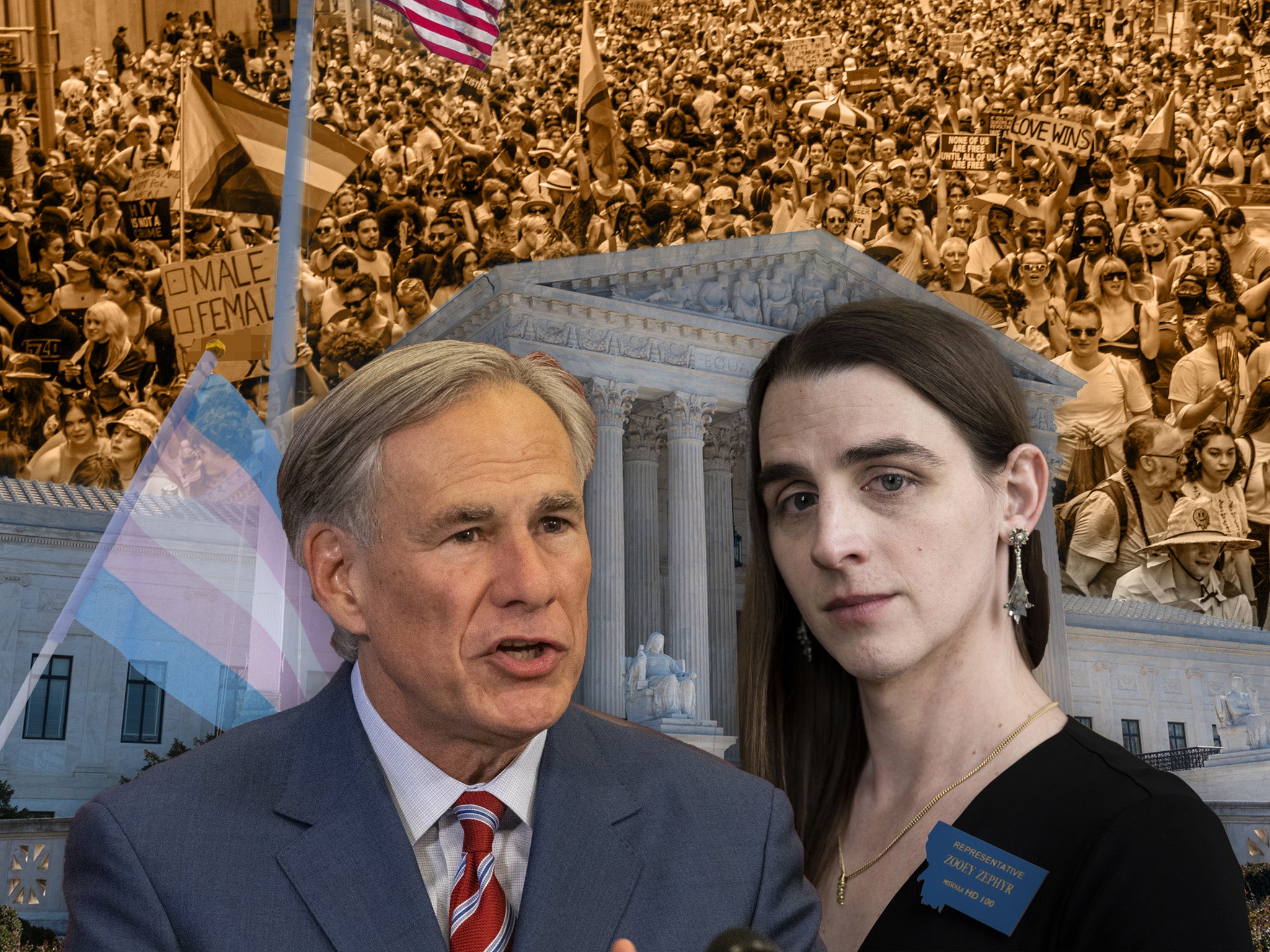

“I think that’s probably a little drastic, and I’ll tell you why,” Nowland says. “Saying to somebody who, let’s say, lives in Texas right now under Governor Abbott – which is not a trans-friendly state under Governor Abbott – you need to leave the country to escape Governor Abbott? No. You can move to New York, you can move to Massachusetts, you can move to California. Now, first of all, you shouldn’t have to move anywhere. Let’s be clear about that. We shouldn’t be having this problem. But if the person’s own particular solution is to remove themselves from that state, before I moved to Scandinavia, I would think of moving to different states in this country because most of the things that you and I are talking about are state issues. The federal government keeps trying to butt in, but they’re really state issues. And you know, here in New York, it’s a very positive trans environment. Our healthcare is very good. It’s mandated by the state. The process of legally transitioning in this state is not draconian. It’s not a breeze, and I don’t think it should be a breeze. There should be some parameters for people to do this, rather than to make sure they just don’t do it on a whim. Because there has certainly been that in the past. So there’s many, many, many states in the United States that continue to be safe havens.”

Do you have a responsibility, I ask Nowland, as an American to try and change society for the better? “I think so,” she says. “I think so. I mean, you know, right now things are such a mess that it’s very easy to just get disillusioned and throw your hands up and say, you know, I’m outta here. But that’s not going to solve any problems. That’s just going to kick the can down the road.”

Nowland finds that in her everyday life in New York state – whether that’s in high-level business meetings or among friends – she experiences very little direct discrimination, even as she watches trans people being increasingly targeted in the political sphere. It’s a strange dichotomy, she says. On the one hand, activists talk about how America has become a hostile environment for trans people, and the laws and the words of politicians certainly seem to underline that. But “individually, I continue to have very little difficulty. One-on-one, in small groups of people. Either they’re totally accepting of me or they’re doing a very good job of concealing that they’re not, and, candidly, at the end of the day, the result is pretty much the same. I get to live my life and do what I need to do. Which I think is curious — all of this political rhetoric doesn’t seem to filter down into my real life experience. And that may be just because, when people know you personally, they have a different slant on things.”

For her part, Rynn Willgohs also finds that people are much more respectful face-to-face. She continues to run educational sessions and diversity training for businesses and church groups, where she encourages people to send anonymous questions to an email account that they’re too embarrassed to ask out loud. A lot of the time, she says, people are surprised that she approaches the issue with humor. It helps to loosen people up, to get them used to interacting with a trans person, and to realize that trans people are the same as them.

Willgohs strives to keep her sessions open and informative, and she’s not afraid to explore difficult issues that require some nuance. As a former nurse, she’s happy to talk through gender-affirming medications and what they do to the body, as well as surgery and when it should be performed. She’s also keen to dispel misinformation about medical interventions, especially when it comes to children: “Gender-affirming care for children is a real hot-button issue. And I don’t think the government should have any say in what a parent, a child, a social worker, or a psychiatrist and a medical provider do. It’s the same thing with abortion. It shouldn’t be anybody else’s business… They say to me that children shouldn’t be having surgeries or things with lifelong effects or whatever. It’s like: Yeah, you’re right. They shouldn’t. However, North Dakota doesn’t have any gender-affirming surgeries [for children]. So it’s a moot point in this state to pass a law for something that doesn’t even happen here.”

When people bring up single-sex spaces, Willgohs tries to take it back to practicalities: “These laws and these rules and regulations as far as female spaces go have been around for probably a decade or more. And I don’t want to be in a space where I’m not welcomed… I don’t think people understand that, you know, it’s really hard to navigate those spaces as a trans woman too. And I don’t want to make anybody feel unsafe or uncomfortable.”

Wynne Nowland similarly isn’t afraid to tackle people’s ignorance regarding “over-exaggeration of the facts”. When trans people are open about talking through the difficult issues, she believes it does a lot to neuter hostile political rhetoric. “One of the big things now is the whole trans athlete thing,” she says. "And I get myself in trouble with my own community with this sometimes because I think that’s one of the issues where we need to figure some things out. It’s just not cut-and-dry like a lot of other issues are to me. But even with that being said – that I think there are things that need to be worked out there on both sides – it’s still such an insignificant percentage of what goes on. And if you listen to these politicians on Fox News, you’d think this was happening all over the place and every girls’ swim team had six trans people on it. That’s just factually untrue.”

Rynn Willgohs continues to plan for her move to Iceland, and the dream for TRANSport, she says, is that its services become nationally available to any American who needs them. As time goes on, she believes, the need for them will only grow. And she doesn’t mind if those services are developed through TRANSport itself or through disparate groups; it’s a nonprofit, after all, and she’s not seeking glory. She simply wants to solve a problem.

“Everybody that’s involved with this organization is a volunteer,” she says. “Nobody’s getting paid. The only expenditures we have right now are the nominal fees for the website. That’s it. Everybody else is doing everything – like all the research, processing the applications, doing the intake interviews, talking with people overseas – and nobody gets a dime for any of this work. Everybody is volunteering. So we’re just pushing now for funds.” They didn’t actively start fundraising until the website went up, but they’re confident that they will raise enough to keep going. And because of how they work, costs per applicant will be kept low: “Even if somebody needs every single service that we offer, we’re expecting to spend less than $2,000 per person.”

Wynne Nowland, meanwhile, is the happiest she’s ever been: “I’m very happy in my life right now. I could have been a lot happier had I [come out] sooner. So that’s one thing I tell people: Don’t waste time. You can have wealth, you can have all sorts of things, but there’s two things you can’t get more of. That’s time and your health.”

“The other thing I would say to people — and again, this is specific to where you are, but in many states in this country – this is not as desperate a situation as sometimes it seems,” she adds. “People will surprise you. There’s always going to be haters out there. There’s haters for everything. There’s haters for sports teams. That’s just human nature.” She smiles. “But people will surprise you.”

Register for free to continue reading

Registration is a free and easy way to support our truly independent journalism

By registering, you will also enjoy access to The Independent app, exclusive newsletters, commenting, and virtual events with our leading journalists.

By clicking ‘Create my account’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy policy.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

Already have an account?

By clicking ‘Register’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy policy.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

By clicking ‘Register’ you confirm that your data has been entered correctly and you have read and agree to our Terms of use, Cookie policy and Privacy policy.

This site is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy policy and Terms of service apply.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments