Top-secret files shed new light on Argentina’s ‘Dirty War’

Cleaners stumble across classified documents linked to military junta behind 30,000 deaths

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Top-secret files dating back to Argentina’s “Dirty War”, including an extensive inventory of blacklisted artists and journalists, have been discovered gathering dust in an air force building in Buenos Aires.

Among the 1,500 files and 280 documents is a blacklist, almost exclusively made up of well-known personalities from artistic and intellectual circles.

In the document, each name is given a number between one and four depending on a perceived “danger” level. The list includes several figures of international repute, including the folk singer Mercedes Sosa, who died in 2009, as well as tango musician Osvaldo Pugliese and novelist Julio Cortázar, both also deceased.

In the last military dictatorship, between 1979 and 1983, up to 30,000 people are thought to have been tortured and killed. The files are expected to be published by the government in the coming months, once they have been fully analysed. “This find will surely have a big impact,” said Gastón Chillier, executive director of CELS, an NGO specialising in human rights. “This is the first time documents of this kind have appeared from the military junta, the very highest level. The historic importance might also help future human rights trials [for crimes committed during the dictatorship].”

The files were reportedly discovered by chance last Thursday during a routine clean of the lower-ground floor of the Condor Building, the air force headquarters in Buenos Aires. The information was passed on to the Ministry of Defence.

“The discovery shows that the hope we’ve all maintained that there might still be documentation out there [relating to the dictatorship] hasn’t been in vain,” said Argentina’s defence minister Agustín Rossi at a press conference where some of the files’ contents were revealed.

Among the disclosed information is an attempt to supress discussion of crimes allegedly carried out by the junta. In one document, military officials are instructed to avoid referring to anyone as “disappeared”, a term that became common currency during the period because of the military’s penchant for burning victims’ bodies or throwing drugged prisoners from aircraft into rivers so relatives would never find them. Instead, officials were told to talk of “requests about the whereabouts of a person”.

The documents also reveal that there were 280 meetings between the junta inner circle between 1976 and 1983, according to original records pulled out of the Condor Building.

“We always thought there might be more information out there, hidden somewhere or outside the country,” added Mr Chillier. “In one sense there hasn’t been a discussion about what happening during the dictatorship from those who are responsible – so these documents will prove a valuable insight into the junta’s political reasoning, economic policies and state terrorism [in general].”

The news was also greeted positively by human rights groups such as Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, the Nobel peace prize-nominated group of mothers of disappeared sons and daughters searching for their grandchildren, the some 500 “stolen babies” taken from their soon-to-be-killed parents and brought up in new homes under false identities. “This is excellent news,” said the group’s head lawyer Alan Iud. “This shows there is still a lot to be done in terms of searching for files.”

The scarcity of information on the so-called National Reorganisation Process from the mouths of the military stems from its virtual pact of silence. The first high-profile officer to break this code was Adolfo Francisco Scilingo, who confessed to his role in “death flights” in a media interview in the 1990s and is now serving a 30-year sentence in Spain.

The reinitiation of human rights trials linked to the dictatorship became state policy in 2003 under the presidency of Néstor Kirchner, the husband of the incumbent Cristina Fernández de Kirchner. Previously, laws had controversially looked to draw a line under the past by pardoning all but the highest-ranking officials.

Last year, 134 sentences were handed down in dictatorship-related human rights trials, while there are currently more than 200 preliminary hearings taking place.

In May, the junta’s most notorious figurehead, its former de facto leader Jorge Rafael Videla, died in prison at the age of 87, while on trial for his role in the infamous Plan Condor, the regional coordination between military dictatorships.

The blacklist: Targeted by the junta

Mercedes Sosa

Mercedes Sosa (above, picture credit: getty) was a popular folk singer throughout the rule of the junta. She sang songs about the life of the poor and she was part of the left-wing nueva canción movement. Sosa, who died in 2009, abandoned Argentina for Europe in 1979 after government harassment and a ban from the airwaves.

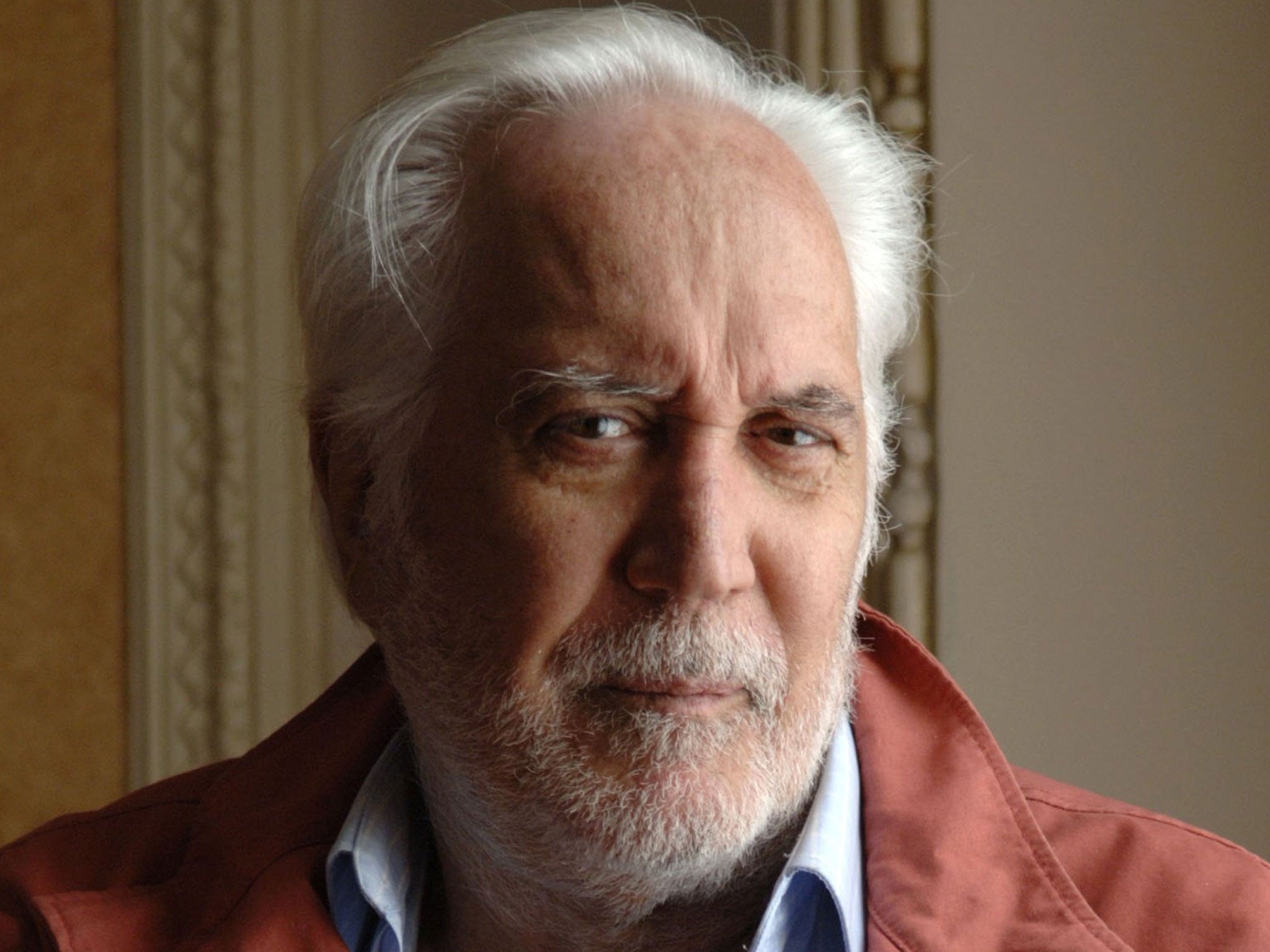

Federico Luppi

His role in the 1974 film “Rebellion in Patagonia” saw him blacklisted for eight years. He went on the run, but it didn’t prevent him from becoming one of Latin America’s biggest stars.The film, about the massacre of striking farm workers in the 1920s, was reportedly used by left-wing guerrillas to train recruits. (Getty)

Hector Alterio

Alterio was a renowned theatre and television actor both in Argentina and abroad. He was targeted by the junta for starring alongside Luppi in “Rebellion in Patagonia”. While in Spain in 1975, he received death threats from the Argentine Anticommunist Alliance. He decided not to return to Argentina. (Getty)

Julio Cortazar

Cortázar was considered one of the best novelists in the country. The writer, who died in 1984, was based in France during the junta’s rule, and was banned from entering Argentina due to his opposition to the dictatorship, along with his support for Chilean President Salvador Allende. (Getty)

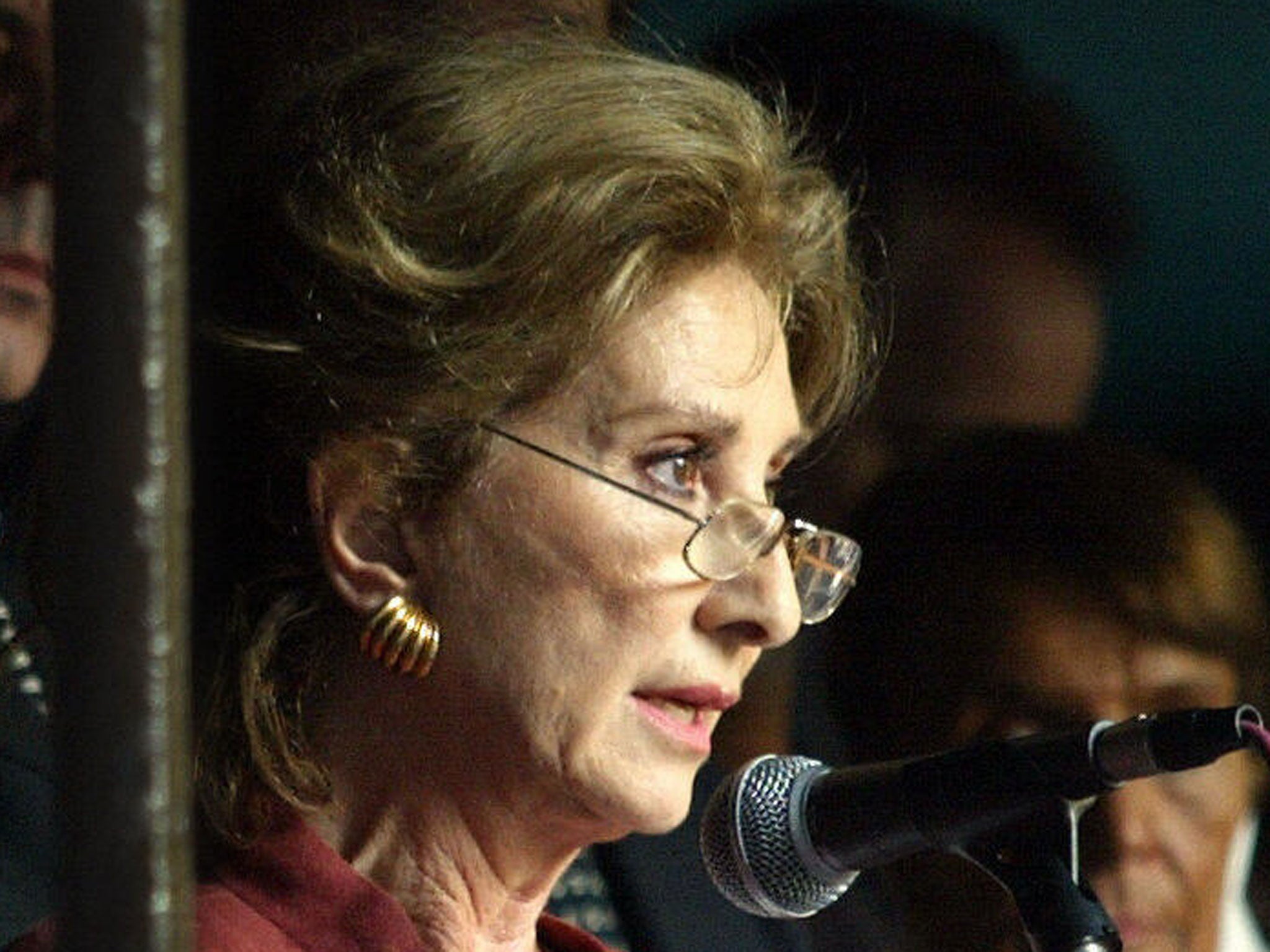

Norma Aleandro

An actress and screen icon in Argentina, Aleandro was best known for her role in the 1985 Academy Award-winning Argentine film “The Official Story”. Her progressive views during the junta’s rule in the late 1970s forced her to go into exile, living in Uruguay. (Getty)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments