Thomas Paine didn't actually write crucial passage of 'Rights of Man', historian claims

Jonathan Clark: Paine 'couldn't have written' account of French Revolution

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

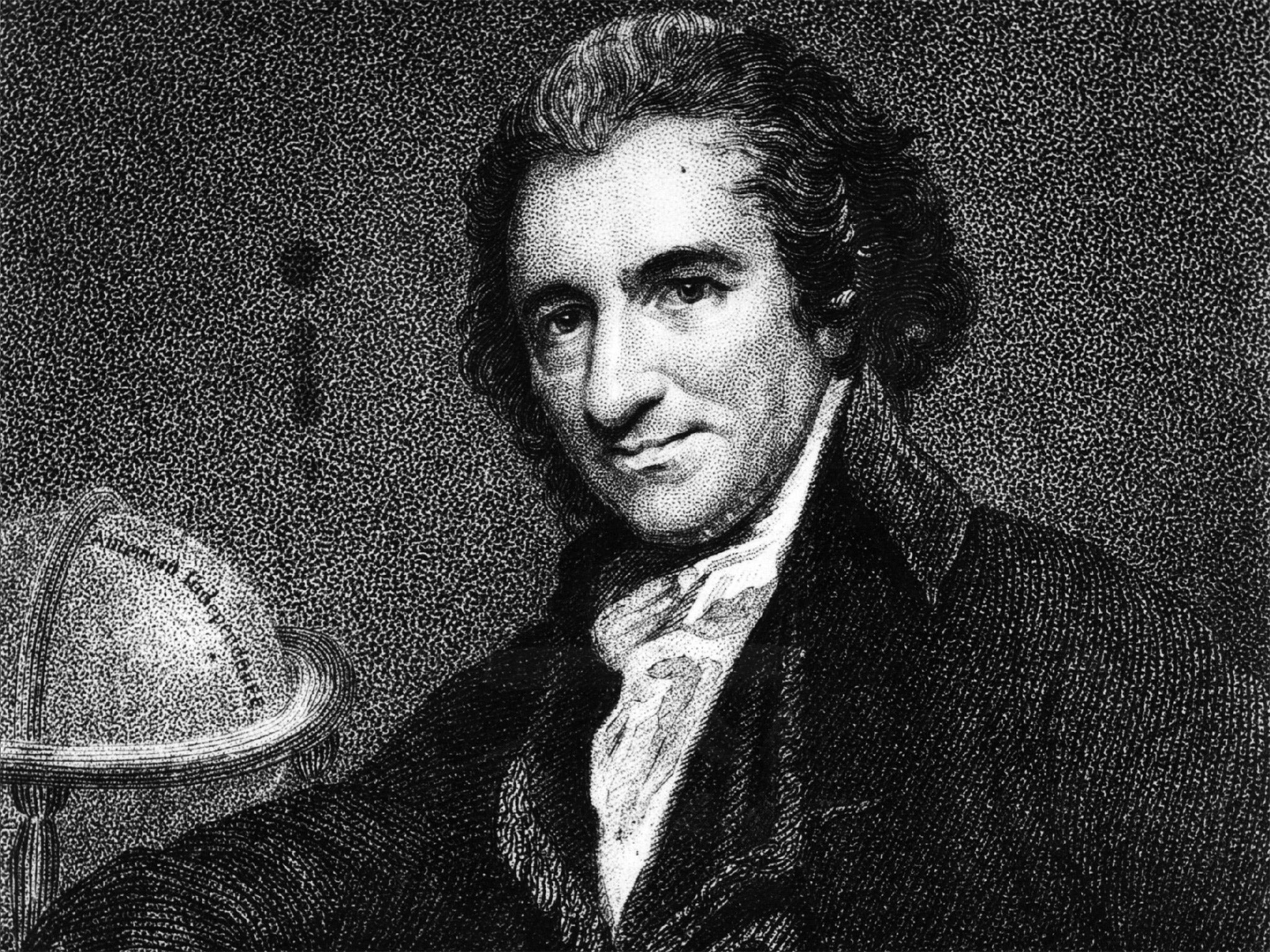

Your support makes all the difference.One of the founding fathers of the United States, Thomas Paine has also been described as a corsetmaker, a journalist and a propagandist. But the celebrated English political activist and revolutionary may also have been something else: a cunning plagiarist.

A newly published essay by an American academic has claimed that a crucial 6,000 word passage of Paine’s famous 1791 work Rights of Man was not written by him at all, but by his friend the Marquis de Lafayette.

The remarkable claim is made by Jonathan Clark, a professor of history at the University of Kansas, who said Paine’s account of the French Revolution was “different in tone” from the rest of the work and was almost certainly the result of extensive conversations with an uncredited second writer.

“This 6,000-word narrative is eloquent, idealistic and visionary. There is, indeed, only one difficulty: Paine cannot have written it. He wrote it out; some of it he put into his own words; but he cannot have been the primary author,” he writes in his essay, published in the Times Literary Supplement.

Paine’s version of the French Revolution, which forms the central historical passage of the work, has come to be regarded over the centuries as the definitive account of the event, he argues. If it did come from Lafayette, Professor Clark says, historians who have taken the story for granted will have “much re-thinking to do”.

He continues: “Paine was undoubtedly the author of the remainder of Rights of Man, and its readers have naturally looked to that work for an explanation of the French Revolution. But the adulation or blame heaped on Paine’s book by its supporters or opponents has occluded the strangeness of this 6,000-word passage.”

The prose of the disputed section is different to that used by Paine in the rest of the book, Professor Clark claims, as it written in the third person and is often “couched in uplifting generalisations”. Examined more closely, he says, it “seems not to be that of an Englishman at all; it reads like the English prose of a native French speaker”.

During this part of his narrative, Paine also boasts that he is privy to the “secret history” of French politics. But Professor Clark says the Englishman’s “humble social standing” at the time meant he would not have moved in such circles – and in any case, he did not even speak French.

The real author of the account is likely to be Lafayette, who knew Paine well, he concludes. Consequently, this part of his famous book should be read not as the “neutral history” of an Englishman but a “very personal perspective” on the French Revolution. The section “consistently overstates” Lafayette’s role in events and may have been written to conceal the true author’s identity, he says.

The Marquis, whose full name was Gilbert du Motier de Lafayette, was a French aristocrat and military officer who joined the US side in the American Revolutionary War. He is known to have provided Paine with other primary material for his book, and in 1790 wrote to George Washington to advise him that the Englishman’s then unpublished book would contain “a part of my adventures”.

Lafayette’s motive in helping Paine write his history was probably to boost his reputation in France, Professor Clark suggests. “What better way of propagating his version of events, with himself at their centre, than feeding his interpretation to his English friend, a brilliant journalist but one who knew little of France and would have been unable to check Lafayette’s story? And it was a tribute to Paine’s talent as a journalist that he could assimilate such information and use it to such effect.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments