The Janes: How a secret network provided thousands of abortions in pre-Roe v Wade America

Jane, a collective that helped women access free and affordable abortions at a time when the procedure was still a crime, is the subject of a new documentary. Clémence Michallon reports

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When Dorie Barron was asked whether she wanted a Cadillac, a Chevrolet, or a Rolls Royce, she was not trying to buy a car. She was a woman in 1960s Chicago trying to get an abortion at a time when the procedure was still a crime in Illinois. Barron was on the phone; on the other side of the line was the Mob, one of the purveyors of illegal abortions.

“The Chevy was the cheapest, $500,” Barron explains in The Janes, a new HBO documentary about a network of women who provided safe, affordable, and illegal abortions in Chicago in the 1960s and 1970s. “A Cadillac was something like $750, and if you wanted the Rolls Royce–we’re talking about the 1960s here–that was $1,000. That’s what the Mob charged for an abortion.” (Adjusted for inflation, these amounts would respectively total around $4,000, $6,000, and $9,000 nowadays.)

Barron asked for a Chevrolet. The procedure, as she recounts it, was petrifying, hostile, and dangerous. It took place at a motel. The four people there spoke three sentences to her in total: “Where’s the money?”, “Lie back and do as I tell you”, and “Get in the bathroom.” Barron was left bleeding next to another woman who had also needed and received an abortion. “If I had stayed in that room, I’d be dead,” Barron says in The Janes. She and the other woman got up once they were able to do so and went their separate ways.

Barron’s story is the first one told in The Janes, and one that highlights why the group was so desperately needed. The standalone documentary, lasting an hour and 40 minutes, recounts how a group of women, at immense personal risk, decided to help other people access abortions at a time when seeking the procedure could result in serious illness, injuries, blackmail, sexual abuse, or death. The Janes tells a story of activism and solidarity. It addresses the historical context that made the Jane network necessary, while also stripping down the group’s raison d’être to a timeless cause: making it possible for women to access healthcare without fearing for their safety.

Dr Allan Weiland, then a medical student at Cook County Hospital, recounts witnessing “what desperate people will do when they think they have no other choice.” “Women would come in with some type of complication, often a horrendous injury, as a result of an illegal abortion,” he says. Some came with perforated organs. One woman arrived with “horrific burns” after attempting to use a type of acid. “We would see 15 to 20 people a day,” Weiland recalls. “They either went to the operating room, or they went up to the septic abortion ward. And the septic abortion ward was full every day.”

In the late 1950s, Eleanor Oliver was the sole income earner in her household. Her husband was in graduate school. She became pregnant. “At that time, you could not work as a pregnant woman,” she says in The Janes. “At that time, you could not work as a pregnant woman. They saw it as a terrible responsibility to have a pregnant woman sitting behind a typewriter. And forget trying to find a job if you had small children at home.”

Oliver’s abortion took place in what The Washington Post called an “abortion speakeasy” in a May 2022 piece about reproductive rights. “I was told ahead of time [the doctor] might ask you for a kiss, he might ask to hug you, cuddle you or I don’t know, whatnot all,” she says in The Janes. “I was terrified.” Oliver did not receive anesthesia, because she had to “be able to get up and walk out of there as if nothing had happened. And I did.”

In 1968, Oliver met Heather Booth. Four years prior, Booth had joined the Freedom Summer project, an effort to increase registration for Black voters in Mississippi, and part of the push that led to the passing of the Voting Rights Act in 1965. “During that summer, I learned that sometimes you have to stand up to illegitimate authority, and sometimes there are unjust laws that need to be challenged,” Booth says in The Janes. By the time she met Oliver, Booth had become involved in women’s issues, and had helped people access abortions through Dr TRM Howard, a physician and civil rights leader. She attended meetings on “any subject” and ended them by asking people who might be interested in “working on abortion” to come and speak with her. “And that’s where I met Heather,” she says.

The women who started the Jane network, according to the documentary, were at once galvanized by the anti-war movement, inspired by the civil rights movement, and disillusioned by politics and the sexism they encountered in their daily lives. Once Booth had found “12 or so women”, they gathered at Oliver’s house and talked. “When everyone felt ready to take this on, I gave them whatever materials I had, and Jane in effect started,” Booth recalls.

The group ran an ad in an underground paper and left notes on bulletin boards telling people to call “Jane” for abortion counseling. The phone number was Oliver’s, but she didn’t want people to ask for her by her real name. She landed on “Jane” because she felt that “nobody [was] called Jane anymore, and it’s a nice, simple name.” Her answering machine instructed callers: “If you have a message for the Olivers or for Jane, please leave your name and number and we will call you back.” It was, she says, “like she lived there.”

Members of the Jane network wrote down callers’ information on index cards, which were then allocated among the group as cases to take on.

Women calling Jane were given a counseling session, and then an address. Some of them brought their children, their husband, or other people for support. Members of Jane made a point to keep the experience as reassuring and comfortable as possible. The process took place in two locations: “The Front”, where people waited, and “The Place”, where the procedure took place. Women were driven between both locations, which varied depending on which spaces were available. They were asked to pay what they could. The abortions were done by a man identified in the documentary only as Mike, who had learned how to perform them from a surgeon from Detroit. In time, Mike taught women from Jane how to perform abortions themselves. According to The Janes, the collective performed an estimated 11,000 “safe, affordable, illegal” abortions between 1968 and 1973.

The group’s activities were shaped by their illegality. “We were criminals,” Judith Arcana, a member of Jane, says. “We were felons.” The Janes could set up a clinic in just 15 minutes and leave within five minutes if needed. “Everybody knew [about the collective],” Arcana asserts at one point. “They didn’t come after us. And they certainly knew what was going on.” The women who came to Jane, we are told in The Janes, included “daughters, wives, mistresses of police” and other officials.

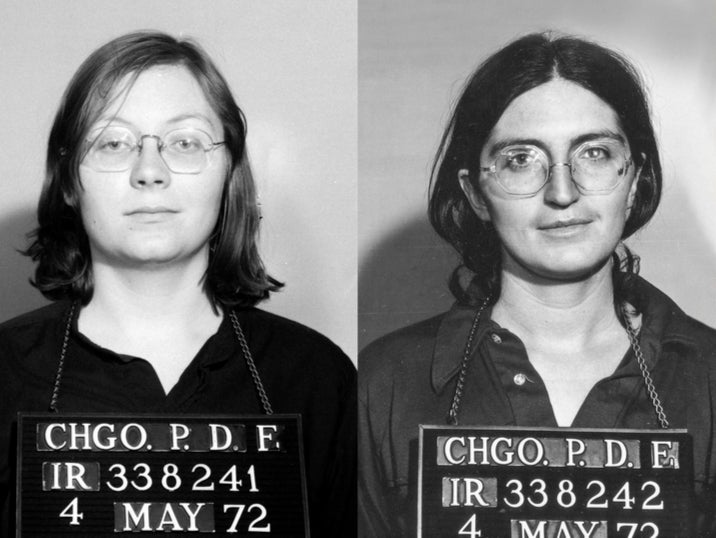

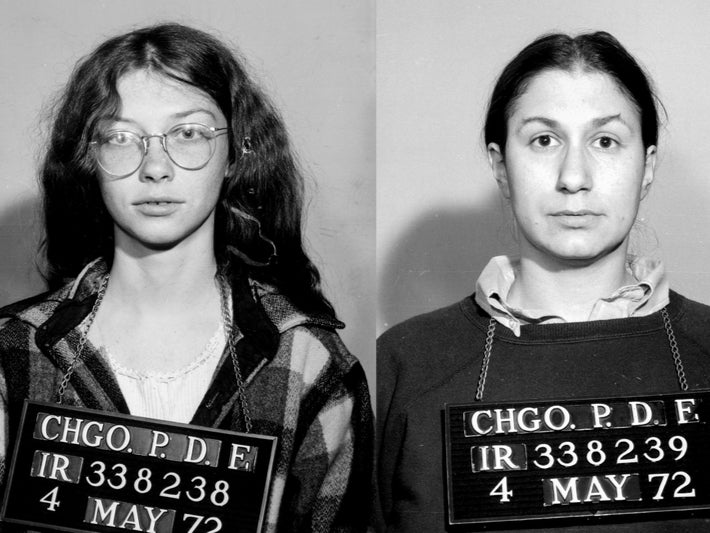

Criminal charges did come, though. On 3 May 1972, Chicago police went into an apartment in the South Shore neighborhood, which was being used by the Janes as “The Place”. Seven members of the collective – according to Vanity Fair, Susan Gallatzer, Abby Gollon, Judith Arcana, Madeleine Schwenk, Martha Scott, Sheila Smith, and Diane Stevens, whose ages ranged from 21 to 30 – were arrested and charged with performing abortions and conspiracy to perform abortions. If convicted, the women could be jailed for the rest of their lives.

The Janes spoke with lawyers, nearly all of whom were men. “The men were, in different ways and with different tones, so condescending that it was impossible,” Arcana says. “How could we possibly hire these guys to represent us when they couldn’t even see us?”

Marie Leaner, a Jane member who was not a defendant in the case, got in touch with Jo-Anne Wolfson, a criminal attorney she trusted with “political cases”. At the time, Roe v Wade was under consideration by the Supreme Court, so Wolfson, we are told, “stalled” and delayed the case by filing various motions.

On 22 January 1973, the Supreme Court released its ruling in Roe v Wade, protecting abortion rights across the US. Charges against the seven women were dropped. The Jane collective folded. And, as The Janes notes, the septic abortion ward at Cook County closed as it was “no longer needed”.

The Janes started airing on HBO Max on 8 June, a month after the publication by Politico of a draft Supreme Court opinion suggesting Roe v Wade would be overturned — a move that was confirmed on Friday 24 June, with the publication of an opinion ending the constitutional right to abortions. This has made The Janes more timely than even its directors thought it would be. (As one headline put it at The Cut: “The Women of Jane Risked It All. Will You?”)

Emma Pildes, who directed the documentary with Tia Lessin, told The Hollywood Reporter of the coincidence: “For a couple of years now, we’ve been working on this film and that’s sort of the place we’ve been: Hyper-aware and spurred on by all the things that were happening in the news cycle, with the high court and at the state level. It was still quite stunning just a few weeks ago to see the leaked decision. You can’t believe it’s true. It’s a nightmare.”

Eleanor Oliver herself, now 85, told The Washington Post columnist Petula Dvorak of recent developments: “Like I said to my daughter, it’s your ballgame now. You’ve got to win this one.”

The Janes is available to stream on HBO Max

This story was originally published on 15 June and was updated on 24 June, after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v Wade and ended the constitutional right to abortion care